Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Hilarious (and Totally Wrong) Misconceptions About Childbirth

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Hilarious (and Totally Wrong) Misconceptions About Childbirth

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Top 10 Truly Crazy Victorian Humbugs

The word “humbug” originated in 1751. Roughly speaking, the word means “trickery and fraud.” When a person, like P.T. Barnum, is called a humbug, it’s implied that they are a trickster and charlatan, which Barnum most certainly was. Here are 10 hoaxes, frauds, and tricks from the 1800s. All of them are pure humbug.

10 Missing Links

Charles Waterton’s 1825 book Wanderings in South America was a well-received record of his trips to Guiana and of the people, sights, flora, and fauna that he encountered there. It was written more as an entertaining travelog than a scientific study, but it inspired many later scientists and explorers to visit Guiana themselves. One aspect of the book, however, caused some controversy. Waterton was also for his talent as a taxidermist, and he returned from each of his trips with a literal boatload of preserved specimens, which he displayed in his home as a museum for all to peruse.

In the frontispiece of his book was an illustration of one specimen in particular—the head and shoulders of an animal he only called the “Nondescript.” The features of this animal’s face were distinctly human in appearance, yet this human face was set on a clearly simian body. Though Waterton hadn’t preserved the whole animal (because it was apparently too large), he did say that it had a monkey-like tail when he encountered it.

Soon after publication, the rumors started. Some said that the Nondescript was a native man whom Waterton had shot, not a monkey. Waterton bribed customs officials to look the other way to bring the head into the country and was displaying evidence of his crime in his museum. It was said that many professionals were fully aware of this but were ignoring it to avoid getting Waterton in trouble. His friends, many believed, were sick with worry over Waterton’s mental and moral state because of these matters.

None of the rumors were true. Experts who examined the specimen and those in the know all agreed that the Nondescript had been cleverly sculpted from a howler monkey. Charles Waterton, after all, was a very talented taxidermist.

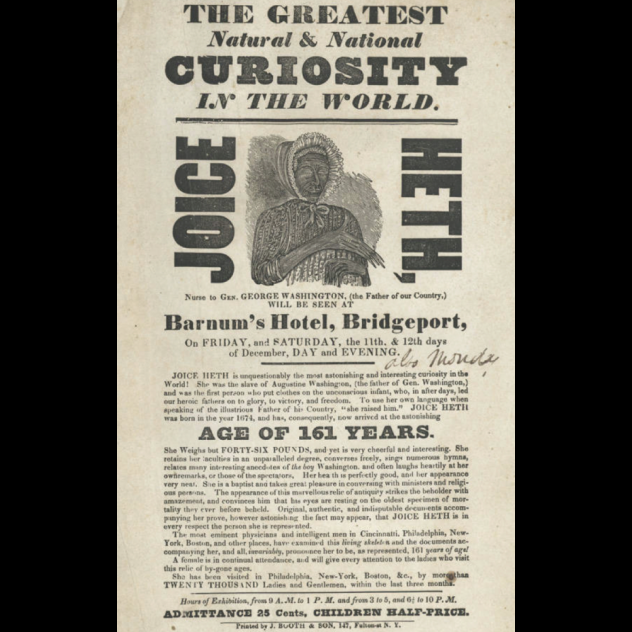

9 Everybody Was A Baby Once

Joice Heth had been a slave her whole life, and she was old . . . very old. In fact, when she was displayed in various public forums in 1835, she was billed at 161 years old. If that wasn’t enough, she was also said to have been the nursemaid of George Washington himself!

This extraordinary “fact” was advertised in newspapers prior to her appearances, generally with expert opinions verifying the story. The old woman would tell stories of her past as a slave and of the precociousness of the young George Washington. She would even sing extremely old nursery songs that she once used to lull the little future president to sleep.

Heth’s fame was entirely due to P.T. Barnum, who had picked her up from a less successful showman. Barnum himself had written and mailed the “expert opinions” that had convinced the newspapers to advertise Heth’s show. When public interest in Heth began to cool, Barnum wrote an anonymous letter claiming that Heth was actually a machine made of whale bone and leather. The crowds flocked out to see her all over again.

8 Good Stories Are Hard To Find (And Prove)

Newspapers in the 1800s were easy targets for hoaxes because they were in a constant battle to be the first to publish important news. Often, a paper wouldn’t check too closely before publishing a spectacular story, lest another paper print it first.

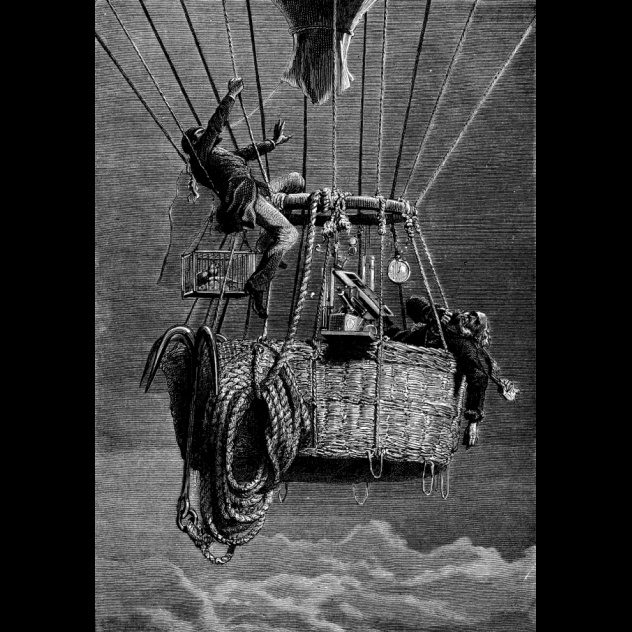

It was in this environment that on April 13, 1844, The New York Sun announced the stunning story that the North Atlantic had just been successfully crossed in only three days by a manned balloon. The balloon, the newspaper reported, had been constructed by a team of well-known balloon enthusiasts, including Monck Mason and Robert Holland, who had previously flown from London to Weilberg, Germany. The men’s intention had been to fly from Wales to France, but the balloon had been blown off course, and they found an air current that carried them safely across the ocean in record time, opening up all sorts of new possibilities in international travel.

The public was amazed, newspapers were sold, and two days later, the Sun had to admit it wasn’t true. Though short, the one-day lifespan of the infamous “Balloon Hoax” had its intended goal: Edgar Allen Poe, who had a sick wife and mother, got some sorely needed cash for handing the story to the newspaper.

7 An Oldie But A Goodie

The Tower of London once housed exotic animals for the English royalty, as lions, tigers, elephants, and more were occasionally gifted to the English royals by the royalty of other countries. For several hundred years, the Tower of London was also a public zoo where the average Londoner could see the most unusual creatures. Starting sometime around 1680, it became a tradition to tell gullible targets that the lions of the Tower would be washed annually on April 1 and that they really should come down to see this unusual event. Sure enough, each April 1, a gaggle of hopefuls would wander around the Tower waiting for the show that would never come.

You’d think the joke would get old after awhile, but in March 1860, an unknown wit mailed out official-looking cards to a vast multitude of people. The cards read:

Tower of London.—Admit the Bearer and Friend to view the Annual Ceremony of Washing the White Lions, on Sunday, April 1st, 1860. Admitted only at the White Gate. It is particularly requested that no gratuities be given to the Wardens or their Assistants.

Sure enough, that Sunday, the streets were packed as people endeavored to discover the location of the “White Gate,” which didn’t exist . . . not that it would have helped. All of the Tower’s animals had been moved to a zoo 25 years earlier.

6 Man Of Action

James Barry had a career that was most remarkable. As an assistant surgeon in the army, he spearheaded sweeping medical changes to improve the health and lives of the soldiers in the field as well as for military prisoners and lepers. Barry performed the first successful cesarean section in 1826 and was eventually made inspector general of military hospitals. Barry had a temper, however, and fought several duels, and he was once accused of having a homosexual relationship with Lord Charles Somerset, which resulted in a libel action. Despite this accusation and his temper, Barry was a well-respected surgeon and considered to be a well-rounded character by all.

Barry died of dysentery at the age of 76 in 1865, when an epidemic of the disease was sweeping through London. It was only after this that he was revealed to be a woman. Barry’s real name was Margaret Ann Bulkley, and she was niece to the celebrated artist and professor James Barry of London’s Royal Academy. Her mother and some of her uncle’s friends had conspired to pass Margaret through medical school, during which time the girl embraced her male identity as James Barry and never looked back.

5 The Great Escape

On November 9, 1874, The New York Herald lent its front page to an astounding announcement that every dangerous animal in the zoo had escaped and was wandering the streets of the city, killing anyone foolish enough to be out. The trouble began when a reckless zookeeper annoyed a rhinoceros enough for it to bust out of its enclosure and gore him to death. Attempts to capture the loose rhino resulted in the animal accidentally breaking the enclosures of all the other animals. Soon, lions, tigers, elephants, bears, hyenas, and more were wandering about the city. The newspaper reported a number of unfortunate deaths and a few acts of courage: A General Dix managed to drop a leopard with one expert shot, and John Morrisey, a well-known gambler and politician, managed to land a deadly punch to a tiger’s head.

The article panicked the city, causing people to lock themselves indoors wherever they were when they heard the news. That’s a bit odd, since the last paragraph of the article read, “Of course the entire story given above is pure fabrication. Not one word of it is true. Not a single act or incident described has taken place.” Much to the editor’s chagrin, the hoax mostly proved that readers never finish reading articles.

4 A Rose By Any Other Name . . .

In 1874, a letter published in newspapers, journals, and magazines across the United States and Europe excited public opinion, for it told of a rare plant documented on the island of Madagascar—a man-eating tree!

The author of the letter, Karl Leche, described the “tree” as having a fat truck (a bit like a pineapple) with huge, thick leaves lined with fang-like projections, all levered so they could close around anything on top of the plant. Leche also explained how he witnessed local natives feeding a sacrificial victim to the horrid tree, which then took 10 days to digest all but the bones of the victim.

Karl Leche, however, never existed. Years later, the story was attributed to a creative newspaper man named Edmund Spencer. Nevertheless, explorers continued to scour Madagascar for the nonexistent plant for the next 60 years.

3 The Centenarian Soldier

On April 3, 1877, New York City lost one of its most prominent citizens, Captain Frederick Lahrbush, at the tender age of 111 years old. Lahrbush arrived in New York City in 1848, claiming to have been born in London on March 9, 1766. He stated that he had joined the British Army in 1789, served with the Duke of York in 1793, saw General Humbert surrender to Lord Cornwallis in 1798, captured Copenhagen with Nelson in 1801, was present at an interview between Napoleon and Alexander that led to an important peace treaty, fought under the Duke of Wellington from 1808 to 1810, and served as an officer of the guard at St. Helena in charge of the deposed Emperor Napoleon, with whom he became friends!

Simply put, Lahrbush somehow was magically present at every historically important military event since his birth and then moved to New York at the age of 82. For some reason, New Yorkers embraced him. He was given his own seat at church. Englishmen of high social status always visited him when they came to New York, and high-ranking military men were also frequent visitors.

Lahrbush was old, of course, but nowhere near the age he claimed. He was never a captain, either. He had never been at the various military events he’d claimed, and he certainly never met Napoleon. In fact, he had been discharged from the army after just nine years of service.

It’s hard to say if the citizens of New York actually believed all of Lahrbush’s stories or if they just enjoyed the depth of his tall tales. Lahrbush also had a habit of giving out “genuine” locks of Napoleon’s hair as special “thank you” gifts to the various benefactors who supplied his income. Each recipient thought they had the only such artifact, which has caused endless confusion in attempts to authenticate actual hair from the emperor ever since.

2 Too Good a Tale

One of the most frequently told ghost stories of the 19th century was of a visit that Silas Weir Mitchell, well-known physician from Philadelphia, received from a little girl.

It was a cold winter’s evening when a knock came at Mitchell’s door. When he answered, he found a thin, shivering girl, clutching a threadbare shawl about her shoulders. She pleaded that the good doctor must help her mother. It was late, past Mitchell’s work hours, but the girl convinced him to follow her into the cold night. When they reached the small apartment where the girl’s mother lay sick in bed, Mitchell recognized her as a woman who had once worked for him. He could also see that she was suffering from pneumonia. After ordering the necessary medicines, Mitchell made the woman as comfortable as possible while congratulating her on having such a brave little daughter. However, the woman claimed her daughter had died a month before. Mitchell, realizing he hadn’t seen the girl for some time, glanced around the room and saw the little girl’s shawl on a nearby shelf. It was both dry and warm and couldn’t have possibly been out in the rough weather of that winter’s evening.

It’s a good story, but it never happened; Mitchell made the whole story up and told it himself during at least one medical meeting that he attended. The story took on a life of its own from there, spreading through rumor, idle talk, and print publications until it was known throughout the country. Later, Mitchell tried to disown the story but found that it was too late to stop it. Even 35 years after his death, the story was still remembered by people he’d told it to as a true story. Mitchell couldn’t escape either the story or the curiosity seekers who inevitably asked about it for the rest of his life.

Ironically, Mitchell was haunted by a ghost that never existed.

1 Crocodile Dundee’s Great-Grandpa

In 1898, adventure had a new name—Louis de Rougemont. In a series of articles written for The Wide World Magazine and later compiled into a book, Rougemont astounded audiences with adventures from his 30 years spent in the wilds of Australia with the natives. Among other anecdotes, he wrote of a man nearly being dragged out of his boat by an attacking octopus, his own ship being attacked by war canoes (which caused his stranding in Australia), riding sea turtles, training pelicans to fish for him, living and fighting among cannibals, escaping a ring of alligators, and wearing stilts in a battle to frighten the native enemies.

Rougemont was often accused of fraudulence but was just as often defended by his publishers. What finally stopped him was something that even his publishers didn’t see coming—the wife and family he’d left in Sydney in 1897. Rougemont’s real name was Henri Louis Grin, and he had married Eliza Ravenscroft in 1882. They had seven children together before Henri vanished with a diary written by a bushman named Harry Stockdale, which was apparently the inspiration for Rougemont’s later fictional life.

Garth Haslam has a degree in Anthropology and specializes in folklore and religious studies. He’s been digging into strange topics for over 30 years and posts his research on varying anomalies, curiosities, mysteries, and legends at his website, Anomalies—the Strange & Unexplained. Check it out at http://anomalyinfo.com/.