History

History  History

History  Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

10 Mysterious, Mythical Substances Thought To Have Great Power

For generations, mankind has been searching for some of the same things. We’re looking for wealth, for a magical cure for the world’s aches, pains, and illnesses, and for a way to forget the memories that haunt us. Along the way, we’ve created legends and stories about the mythical, magical substances that will allow us to make all of those dreams come true.

10 Lyngurium

The first mention of a gemstone called lyngurium came from the works of Theophrastus of Eresus. According to Theophrastus (who is often credited as being the first lapidary for his work on the properties of gemstones and his theories on their formation), lyngurium was nothing more than solidified lynx urine.

Theophrastus was writing in the third or fourth century BC, and his work was repeatedly cited well into the Renaissance. Countless medieval lapidaries feature the lynx stone despite the fact that no one has ever truly seen one. Translations of the original texts describe the stone as solidified urine and claim that the urine of a wild lynx makes a better stone than the urine of a tame one. Males produce stronger stones than females, and finding a stone can be difficult as the lynx will bury it.

The stone is a clear yellow and has attractive, almost magnetic properties. But lyngurium works on nonmetallic objects as well and is specifically cited as working on plant materials like straw and leaves.

It was also rumored to have curative properties. Supposedly, if the stone was put in liquid that was then consumed, it had the power to dissolve bladder stones and cure jaundice—and some claimed that a person only needed to look at the stone to be cured.

Later writings added even more outrageous claims to the list of the stone’s magical powers, with one suggesting that the stone had the power to change a person’s gender entirely. By the time the stone was showing up in medieval texts, it could protect a house and a person from harm and was particularly effective against stomach and digestive complaints.

Anyone fortunate enough to find the stone could soak it in warm cow’s or sheep’s milk for 15 days. But if one were to try to use it for an ailment other than what it was popularly known to cure, that person’s skull would shatter.

Lyngurium is one of Theophrastus’s “gendered stones,” and he says that male stones are much darker in color than female ones, a common theme in early gem science. Although other early writers like Pliny condemn the idea of the existence of such a stone, those voices were in the minority. Medieval writers added to the mythology of the stone, saying that the lynx held something of a grudge against mankind and stored the precious gems in its throat to keep man from discovering and using them.

9 Azoth

Even those who write about azoth can’t decide exactly what it is. The term started with Paracelsus, who used it to refer to an alchemical substance that he said was a universal remedy. Sometimes, it’s applied to what we now know as mercury, although it’s also used to refer to a base substance or property that is present in every type of metal. Later readers of Paracelsus think that he might have assigned the name to a different substance entirely: his most famous discovery, laudanum.

In the 1920s, Manly P. Hall released a massive compendium called The Secret Teachings of All Ages, and he took a shot at figuring out just what azoth was. He suggested that azoth was an alchemical substance that existed alongside the three basics of salt, mercury, and sulfur. (But these weren’t just the ordinary minerals. These were substances made up of all three, with a different aspect dominating each mixture.)

Azoth was a very real essence of life, and no one was quite sure what it actually was. Some suggestions were that it was something invisible, while others said that it might be electricity, a substance of magnetism, or some sort of eternal fire.

It was also linked to the sphere of Schamayim, which is the manifestation of the Word of God. That Word divided into fire, which created the Sun, and water, which created the Moon. The rest was azoth, a universal mercury that created life.

8 Ambrosia And Nectar

Ambrosia is generally known as the food of the Greek gods and the substance that gives them their immortality, but there is a whole group of legends and myths about the powers of ambrosia. When eaten by the gods, the sacred food turns to ichor, which filled their veins like divine blood and was actually the source of their immortality. When fed to a divine child like Apollo, ambrosia made them instantly grow to adulthood.

Occasionally, ambrosia was used in the mortal realm. In Homer’s Iliad, Patroclus donned the armor of Achilles and led a group of men against Troy. Struck senseless by Apollo, he was then killed by Hector and Euphorbus.

What followed his death was another battle to get his body back for a proper burial. The nymph Thetis interfered to preserve the body with ambrosia to keep it from decaying until Achilles could give his friend a proper burial. When ambrosia is given to a living person, it can make them infinitely beautiful as happened when Athena gave the mortal Penelope a taste of the divine substance.

No one is absolutely certain just what ambrosia was supposed to be. Even though it’s often said to be some sort of fermented honey, it’s also linked to the idea of grape wine. Others have suggested that it’s actually a mushroom called fly agaric (Amanita muscaria).

The satyrs and the centaurs, some of the most infamous creatures of Greek mythology, were said to hold an annual feast called “the Ambrosia.” Depictions of the feast show what look like magic mushrooms alongside the revelers.

7 Orichalcum

Fans of role-playing games probably know orichalcum from the Elder Scrolls series where it’s associated with Orcish smiths and the high-quality armor they make from the metal. But the idea of this mysterious metal goes back a lot further than Elder Scrolls lore. The term was used by Homer and later Plato to describe an unknown metal supposedly worked by Atlanteans.

Orichalcum was the source of much of Atlantis’s wealth, and according to Plato, the only thing worth more was gold. Translating “orichalcum” to something along the lines of “mountain brass,” Plato is vague about just what orichalcum is—aside from being a major source of the wealth of Atlantis. He describes it as having the color of fire, and other ancient texts refer to it as a golden metal associated with deities like Aphrodite.

One ancient source, De mirabilibus auscultationibus, says that it was made by combining copper with a particular type of earth that only came from the Black Sea. By the time the Romans were writing about this mysterious metal, the name became aurichalcum and it was associated with gold. Pliny suggested that by the time he was writing, no one was mining the metal any longer as all the known sources had been depleted.

There have been all kinds of guesses as to what a real-world orichalcum might be—from phosphoric bronze to any number of copper alloys. Whatever it was, the ancient Greeks said that it had been invented by Cadmus, the founder of Thebes. All that makes it seem likely that orichalcum was about as real as Atlantis itself, but in 2015, a group of divers recovered some from a 2,600-year-old shipwreck off Sicily.

When the 39 ingots were analyzed, they were found to be 75–80 percent copper, 15–20 percent zinc, and minute amounts of iron, lead, and nickel. Archaeologists think that the metal would have been used mainly for decorative purposes, and the find confirms that at least part of Plato’s tale is true: Orichalcum and the artisan workshops of the sixth century BC made one city—Gela, not Atlantis—very wealthy indeed.

6 Unspoken Water

Scottish folklore says that unspoken water is one of the powerful remedies for any illness. It must be collected in silence either at dawn or dusk and taken from water that passes beneath a bridge that is used both by living persons and to carry across the dead. Once the water is brought to the home of the person in need of healing, there are a few different ideas of what should be done with it.

Some say that before a word is spoken in the house, the person should drink from the water three times. Other times, the water is thrown over and around the house to summon its purifying powers, and in some cases, the vessel used to collect the water is thrown over the house as well. Sometimes, the water is part of a larger recipe or ritual, with some texts referring to the use of unspoken water to boil eggs that should be eaten for breakfast.

The power in the water was believed to come not only from the place in which it was gathered but also from the silence of the person who collected it.

5 The Moon Rabbit’s Elixir Of Life

Folklore and mythology tell stories of a number of creatures said to be living on the Moon, and one of them is China’s Moon Rabbit. The story says that when the Buddha dressed himself as a saint and appealed to nearby animals for food, the rabbit was the only one with nothing to give him.

Instead of sharing nothing, the rabbit hurled himself into the fire and offered his own body as nourishment. In his gratitude, the Buddha placed the rabbit in the Moon. There, he spends his time making a mysterious compound known as the elixir of life, mixing his ingredients on the head of a toad.

Another story about how the rabbit came to live on the Moon says that he was sent there to be a companion to Chang’e. Chang’e was the wife of Hou Yi, a legendary archer who was given a magic elixir after he used his skills to destroy nine of the 10 suns that once rose in Earth’s sky.

Chang’e drank the elixir herself and was sent to the Moon as punishment. Once the Moon Rabbit joined her, he was tasked with creating the elixir of life for not only the immortals but for Chang’e as well. Sometimes called the Jade Rabbit or the Gold Rabbit, the Moon Rabbit is also said to be trying to create something else with his mortar, pestle, and mystical ingredients: a pill that will allow Chang’e to return to Earth.

4 The Net

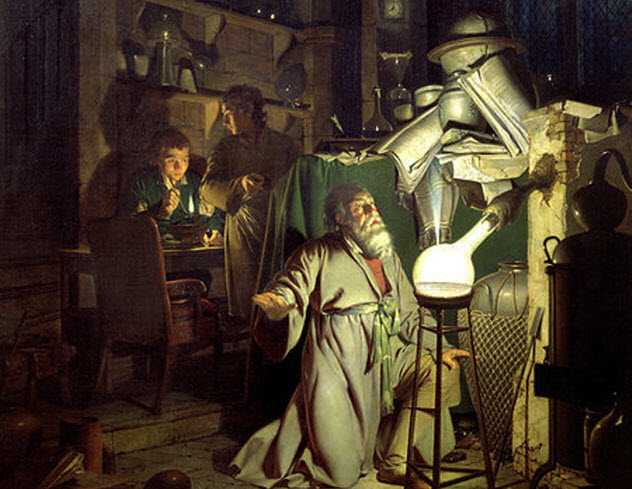

Isaac Newton was one of history’s most famous alchemists, even though his work was kept secret during his lifetime. Recently, researchers have looked at his alchemical notebooks with renewed interest, and they were able to decode and replicate some of his work.

Like many alchemists, Newton was looking for the philosopher’s stone. He built his research on the work of generations of alchemists who had come before him, and he came to the conclusion that a major piece of the puzzle was a substance called “the net.” It’s an odd name, no doubt, and it came from Newton’s idea that ancient Greek mythology was a way of speaking in code, much like his more contemporary alchemists were known to do.

In one myth, Aphrodite (Venus) was caught having an affair with Ares (Mars), and her husband Hephaestus (Vulcan) forged a net so delicate and fine that it couldn’t be seen with the naked eye. He used it to catch the lovers in the act, and Newton believed that the story was actually a recipe for making one of the basic substances of the philosopher’s stone—a substance that he called the net.

Names of the gods (and the planets) were often used as code words for metals, so Newton took the myth and combined it with work that had been done by American alchemist and writer George Starkey. He had created an alloy of antimony and copper that modern-day researchers have been able to replicate.

Although the substance didn’t end up as part of the philosopher’s stone (as far as we know), it’s easy to see why they believed that they had stumbled across something incredible. The surface of the alloy bears markings that were accurately described as crystalline rays, which could easily be interpreted as physical evidence that they were on the right track.

3 Toadstones

The toadstone was thought to be quite literally a stone from the head of a toad. The story seems to have started in the second century with the writing of Kyranides, who said that toads secreted a substance that built up to form a stone that was stored in their heads.

There were a few different ways to harvest a toadstone—from the harmless (waiting for the toad to spit it out and grabbing it before he could eat it again) to the horrible (putting the toad in a pot of flesh-eating ants and waiting until they had consumed everything but the stone). The idea of the toadstone showed up in everything from works on gemstones to Early Modern European paintings, when Agostino Scilla noticed that these mythical stones bore a striking resemblance to fossilized fish teeth.

That ruined the whole idea of the toadstone because it was believed that the stone’s magical powers came from the toad itself. The stone was made from secretions that were viewed as poisonous, so touching the stone to a person’s skin was supposed to cure them of the ill effects of any kind of poison, from snake and insect bites to the humoral imbalances that were believed to cause things like fevers and tuberculosis.

Although most texts suggested that the stone just needed to be applied to the skin to work, there was another belief that swallowing the stone would cure a person of their stomach and digestive ailments. Once the stone was passed, it could be set into a piece of jewelry for further protection. Sometimes, it was also considered valuable protection for a new mother and her child in warding off any fairies that were looking to steal the baby for their own.

Toadstones were highly sought after and even showed up in the inventories of royal treasures.

2 Dragon’s Teeth

We mentioned Cadmus as the creator of orichalcum, but he’s also connected with another mythical substance: dragon’s teeth.

Cadmus (aka Kadmos) received divine instruction on how to select a particular cow and follow it until it sat down. There, he was to found a new city. The city would be Thebes, but there was a problem. He decided to offer the cow to the gods (sometimes Athena, sometimes the Earth) as a sacrifice, but to do that, he needed lustral water.

The water was guarded by a creature that the myths call a dragon, but in Greek form, the beast bore a closer resemblance to a snake than to our modern idea of a dragon. After killing the dragon, Cadmus was instructed to remove its teeth and plant them. A group of fully armed men grew from the mystical teeth, and according to one version of the story, they immediately started fighting—and killing—each other until only five were left. Those five Sown Men, or Spartoi, went on to found the five noble houses of Thebes.

The idea of dragon’s teeth as having mystical properties that grow armed warriors when planted shows up in the story of Jason and the Golden Fleece, too. When Jason presents himself to the king at Kolkhis, he is given some of the teeth that come from the dragon killed by Cadmus.

Ordered to sow the teeth and fight the warriors that appear, Jason ultimately defeats them. Sometimes, he throws rocks into the middle of the group of warriors, who turn on and kill each other. In another version, Medea gives him ointments that make him invulnerable, and in some, the dragon teeth grow an entire field’s worth of warriors.

1 The Water Of Lethe

There are five rivers in the Greek underworld: Styx, Kokytos, Pyriphlegethon (Phlegethon), Acheron, and Lethe. Lethe wasn’t added until later myths and became known as the river of forgetfulness. While Styx, Kokytos, and Acheron touched the land of the living in some way, Lethe was entirely in the underworld and its waters were the stuff of oblivion.

Plato was the first to talk about the powers of the waters of Lethe, and Plato gave the water its ability to make anyone who drinks from the river forget everything. There’s a catch, though. Even though everyone who dies drinks the water of Lethe, it doesn’t work on those who have committed crimes while they were living. They continue to be tormented by the memory of their sins.

Plato also suggested that Lethe allows our spirits to be reborn. Once we die and drink from the river, our memories are erased. When we are finally reincarnated, we start our new lives with a clean slate. That’s how it works for nearly everyone, except Hermes’s son Aithalides. He was cursed with an unfailing memory that carried on through the lands of the living, the dead, and future lives.

The waters of Lethe were also used by the living but only under particular circumstances. Anyone looking for wisdom and guidance from the oracle of Trophonios at Lebadeia was instructed to drink from a small spring near the oracle. The spring was fed with water from Lethe because its powers would clear away all other thoughts and questions.

Drinking from a second spring would allow the supplicant to remember what the oracle had instructed, much like drinking from the underground Lake Mnemosyne would allow the living who ventured into the underworld to remember what they saw there.