Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Fascinating Cases Of Archaeological Or Artistic Theft

Widespread reports of ISIS selling illicitly obtained artifacts have brought to light the importance of ensuring the legality of purchased items. Museums, and to a lesser extent private collectors, often claim to have followed the letter of the law. More often than should be acceptable, their claims have been proven false. Here are 10 interesting cases of archaeological or artistic theft.

10 Italian Conquest Of Ethiopia

In 1937, just before the onset of World War II, Italian soldiers under the direction of Benito Mussolini came to the town of Aksum (or Axum), which housed one of Ethiopia’s most revered treasures—the Obelisk of Aksum, a monument which dates back to the fourth century AD. (Technically, it’s a stele, as it doesn’t have a pyramid at the top.) The city of Aksum was of the holiest places in Ethiopia and a central figure in the rise of Coptic Christianity in the country.

The Italians were pushed out of Ethiopia at the end the war and signed a peace treaty just a few years later, which included the condition that they return any looted artifacts within 18 months. While many items were repatriated, the stele remained outside a United Nations building in Rome. Two more treaties were signed over the coming decades, each with the condition of repatriation, but it never budged. It was finally returned in 2005, though it had to be broken into three pieces for the voyage, as it stands over 24 meters (79 ft) tall and weighs 160 tons. (It was rebuilt when it arrived in Ethiopia.) The stele was described as the largest and heaviest object to ever be transported by air.

One of the main concerns that the Italians raised (one commonly raised by countries asked to return stolen goods) was that the Ethiopians would not take care of it. Italy’s deputy minister of culture, Vittorio Sgarbi, said at the time: “Italy cannot give its consent for a monument well kept and restored to be taken to a war zone, and leave it there with the risk of having it destroyed.” He even threatened to resign if the stele was ever returned, though he didn’t follow through with it. When it was damaged in a severe thunderstorm, he finally relented, saying, “After all, it has already been damaged, so we might as well give it back.”

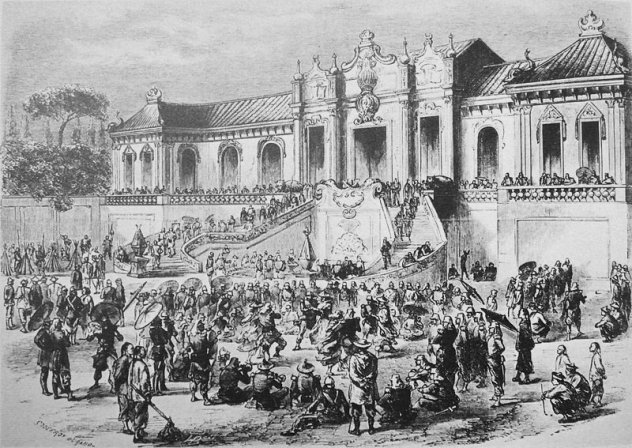

9 Looting Of The Old Summer Palace

Following the defeat of Chinese forces in the Second Opium War, the United Kingdom found itself in Beijing and also in need of, shall we say, “compensation.” To that end, British forces, with a little help from the French, descended on the city and made a beeline straight to Yuanmingyuan (Garden of Perfect Brightness). Since looting had been a recognized byproduct of war for millennia as well as the fact that they need to pay their soldiers and defer the cost of the dead, the Europeans began to take anything they could lay their hands on, while an envoy went to the Chinese to discuss peace talks.

However, the envoy never reached its goal, as they were taken prisoner by the Chinese and tortured until they were dead. Angered beyond belief and out for vengeance, the commander of the British forces, the eighth earl of Elgin, ordered his army to burn Yuanmingyuan to the ground. (If the name Elgin sounds familiar, it’s because his father was the same Lord Elgin who “acquired” the Parthenon [aka Elgin] Marbles.) One of the items stolen was a Pekinese dog, which was given to Queen Victoria and named “Looty.”

Chinese officials estimate that about 1.5 million items were pilfered from the site by the end of the war, with nothing but rubble left behind. Its looting is still a sore spot for the Chinese. Yuanmingyuan was purported to be the greatest collection of art and architecture in the entire country, and virtually nothing survived the British destruction. Even the British recognized its beauty, as a participating officer said at the time: “You can scarcely imagine the beauty and magnificence of the places we burnt. It made one’s heart sore to burn them.”

Investigators have spent decades trying to recover the artifacts, with most of their requests falling on deaf ears. One of Elgin’s descendants, showing a complete lack of understanding, said, “These things happen. It’s important to go ahead, rather than look back all the time.”

8 Russo-Japanese War

Fought between two countries with imperialistic ambitions in Manchuria and Korea, the Russo-Japanese war lasted for nearly two years just after the beginning of the 20th century. In the end, Japan emerged victorious, and it was the first major military conflict in modern times in which an Asian country defeated a European nation. As the area known as Manchuria spans territory both in Russia as well as in China, Japanese forces often found themselves on Chinese land.

Though an estimated 3.6 million artifacts were looted in the time between the First Sino-Japanese War and the end of WWII, one of the most sought after relics was stolen during the Russo-Japanese War—the Honglujing Stele. With its construction dating back nearly 1,300 years, the stele is believed to be of the utmost importance in the study of the Bohai Kingdom. Very few people, even Japanese researchers, have been allowed to look at it.

Housed in the Tokyo Imperial Palace for over a century, the Japanese consider the 9-ton Honglujing Stele to be a “trophy” of their victory in the war as well as the property of the emperor. Thus, they’ve rebuffed Chinese demands to return it.

7 Construction Of The East Indian Railway

Much like the more famous Koh-i-Noor diamond, the Sultanganj Buddha has been a point of contention between the Indian and British governments since its removal from India in 1861. It was discovered by E.B. Harris, the local engineer for the British, during the construction of a station yard at the North Indian town of Sultanganj. It was believed to have been buried in an effort to hide it. Harris himself said, “From these discoveries I conclude that the resident monks had only just time to bury the colossal copper statue of Buddha before making their escape from the Vihar.” The Sultanganj Buddha was whisked away to Britain in the following months and brought to Birmingham by an industrialist involved in the construction of the railway.

Atop a list of stolen treasures that the Indian government would like returned, the statue, which dates back as far as AD 500, has remained in Birmingham. Like all British museums, the Birmingham Museum has steadfastly refused to return it, standing by laws which forbid it from returning major artifacts. (Small, in other words less valuable, items are routinely returned, however.) The British maintain that they have proper ownership of the bronze Buddha, claiming that Harris was the only one who realized its value and saved it from being melted down by the locals.

6 The Morean War

Though the Republic of Venice longer exists, and its naval commander, Franceso Morosini, is more well-known for his destruction and subsequent looting of the Parthenon in Athens, they were also responsible for the theft of a number of artifacts, chief among them being the Piraeus Lion. Thanks to their veneration of Saint Mark, their patron saint, the Venetians would often search for depictions of lions to loot during their conquests.

During the Great Turkish War, a conflict waged between the Ottoman Empire and a collection of European nations collectively known as the Holy League. Various smaller wars between the countries broke out as well. One of them was known as the Morean War, and it was basically between Venice and the Ottoman Empire. As the war raged on, the Venetians and Morosini found themselves in Athens and were determined to take the city. Once they succeeded, the looting began, with the most valuable monument being the white marble lion located in Piraeus, the Athenian harbor.

With its construction dating back to the fourth century BC, the Piraeus Lion had stood in the Greek city for nearly 1,500 years before Morosini and his Venetian soldiers looted it and brought it to the Venetian Arsenal, where it remains to this day.

5 Napoleon’s Conquest Of Italy

Setting an example for future dictators like Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin, Napoleon Bonaparte wished to fill his newly constructed Louvre museum with a virtual encyclopedia of artistic history. He, and much of France’s elite, believed that the French people had better taste and would appreciate the plundered artifacts better than anyone else. Setting themselves apart from most entries on this list, however, they actually stole from fellow Europeans.

First on Napoleon’s long list of victims, which included one of the first coordinated lootings of Egypt, was Italy. The Louvre, briefly known as the Musee Napoleon, was to be the home for the spoils of war, an idea which owes its origins to the Convention Nationale, which deemed valuable works of art as viable for payment for war debts. Some of Italy’s greatest works, including Correggio’s Madonna of St. Jerome and Raphael’s Transfiguration, found their way to France thanks to that decision.

When he was done looting, Napoleon referred to the plundered art as harvest, saying that they would have “all that there is of the beautiful in Italy.” Although they initially felt the legality of their acquisition to be beyond reproach, the French government returned many of the paintings after Napoleon’s abdication and subsequent exile. Some, however still remain in Paris.

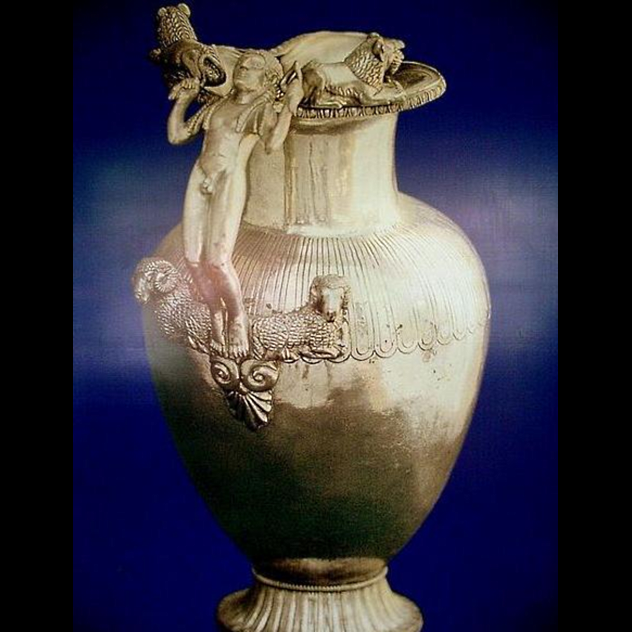

4 Excavation Of The Karun Treasure

While they weren’t personally involved in the excavation and eventual theft and export of nearly 200 pieces from the Karun Treasure, the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art was well aware that they were illicitly obtained and are just as culpable. In fact, they knew from the beginning. Thomas Hoving, the director of the Met, said in his memoirs, “If the Turks come up with the proof from there side, we’ll give the East Greek treasure back. [ . . . ]We took our chances when we bought the material.” (This was very much in the middle of the “don’t ask, don’t tell” period for US museums.)

Collectively known as the Karun Treasure or the Lydian Hoard, the pieces were discovered in 1965, looted from Iron Age burial mounds in western Turkey. Nearly 2,500 years old, the 363 artifacts were unearthed by local treasure hunters and smuggled out of the country over the following two years. Though they were briefly displayed at the Met during the 1980s, the pieces were eventually returned to Turkey in 1993.

To add even more intrigue to this story, one of the most prized pieces in the collection, a hippocamp brooch purported to belong to King Croesus of Lydia, was found to be a replica in 2006. The director of the museum in which they were held later admitted to swapping out the real one in order to settle gambling debts. (He blamed his bad luck on an ancient curse said to reside in the brooch.) It was eventually found a few years later and returned to the museum.

3 Looting Of Berlin During WWII

Though Russia has since returned a handful of the artifacts that their armed forces looted during the aftermath of Nazi Germany’s surrender, many of them still remain locked away in Russian museums and private collections. (However, if you ask Russia, they’ll say that over 90 percent of them have been returned.) Chief among them is Priam’s Treasure, a collection of artifacts discovered at Hisarlik, which is generally accepted to be site of ancient Troy.

Unearthed by an amateur archaeologist named Heinrich Schliemann, the find dates back 4,500 years, centuries before the originally purported owner, King Priam of Troy, was said to have lived. Originally illegally smuggled out of Turkey, the collection of copper artifacts, which includes an exquisite diadem known as the “Jewels of Helen,” found their way to Berlin, where they remained until the Soviets looted them in 1945. Seen by the Russians as the spoils of war (or “trophy art”) the very existence of Priam’s Treasure was denied for decades before it finally turned up in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow in 1993.

The artifacts’ return, either to Germany or Turkey, seems unlikely, as the Russian government has deemed the artwork and artifacts that they’ve kept as payment for the “moral crimes” which Nazi Germany perpetrated on the Russian people. To sum up their attitude, the longtime director of the Pushkin Museum said in an interview in 2012: “A country is liable, with its own cultural treasures, for the damage it inflicts on the cultural heritage of another nation.”

2 Amarna Excavation

Dating back 3,500 years, the bust of Queen Nefertiti, wife of the infamous pharaoh Akhenaten, was discovered by a German archaeologist named Ludwig Borchardt on December 6, 1912. Found in the remains of Thutmose’s workshop in the dig site known as Amarna, the bust was smuggled out of the country and hidden from Egyptian authorities, who had agreed to split the found artifacts. Germany disputes this version of events, claiming that everything was legal and aboveboard.

Recognizing the value of the piece, which has since gone on to gain a reputation as an icon of feminine beauty, Borchardt was said to have “wanted to save the bust for us,” according to a secretary in the German Oriental Company, who was present at the time. It was initially kept in the private residence of the excavation’s financier. Later, it was displayed as a counterpoint to Tutankhamun’s funerary mask, which had brought worldwide acclaim to the British when it was showcased.

Egyptian efforts to repatriate the bust have proved fruitless over the decades, as countless German officials have refused to give the notion a second glance. Adolf Hitler himself declared: “I will never relinquish the head of the Queen,” as it was one of his favorite pieces.

1 Benin Expedition Of 1897

A punitive expedition in retaliation for an attack on the British military known as the Benin Massacre, the Benin Expedition of 1897 was led by Rear-Admiral Harry Rawson, and it had the express intent of destroying every Benin town or village and plundering anything of value along the way as reparations. By the end of Britain’s reign of destruction, the Kingdom of Benin was no more, wiped off the face of the Earth.

When Benin artifacts finally made their way to London, their reception was incredible, with every museum from Europe and the United States hoping to get their hands on a piece of the treasure. (Germany was especially enamored with the looted artwork.) Perhaps the most noteworthy of all the artwork are the Benin Bronzes, a collection of more than 1,000 metal plaques which commemorate the battles, kings, queens, and mythology of the Edo people. They date back to the 13th century AD. Europeans became enamored with African culture after their “discovery,” astonished that a culture so “primitive” and “savage” could have produced something of such high quality.