Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

10 Of The Biggest Branches Missing From The Animal Kingdom

The animal kingdom’s real genetic diversity tends to be locked up in small and easily overlooked little critters whose evolutionary journeys were fraught with carnage and apocalypses that devastated all but a handful of lucky modern-day survivors. Other massive groups haven’t been so fortunate. Some of them were out-evolved by more modern and efficient successors; others were simply dealt a bad hand.

What can we learn from these shadows out of time? One of the lasting legacies of the late great Stephen J. Gould is the idea of natural selection’s ultimate futility. Across geological time, it doesn’t really matter how big your brain is or how efficient your circulatory system is. Giant rocks from space don’t tend to care about that.

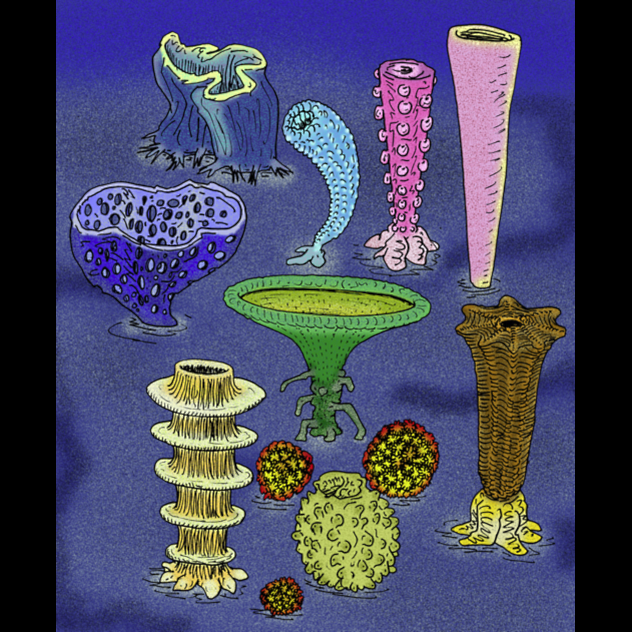

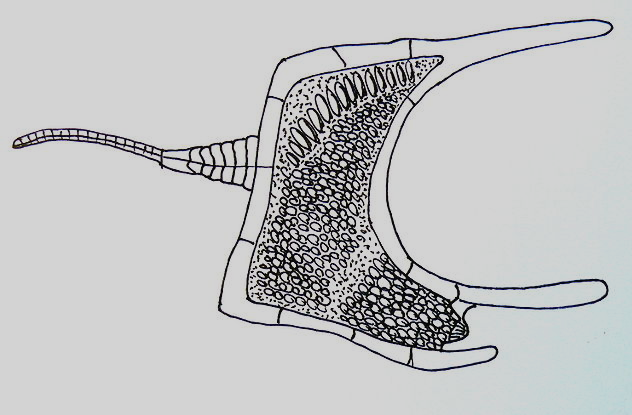

10 Archaeocyathids

Archaeocyathids weren’t long for this world, but they did great things in their brief time. The first archaeocyathids appeared in the fossil record 542 million years ago, in the Precambrian Period. Like modern sea sponges, which they were probably related to, archaeocyathids formed hard, porous calcareous masses, though they were rarely more than 15 centimeters (6 in) high. They formed cup-shaped and tubular structures on the seabed.

Archaeocyathids probably fed even more simply than modern-day sponges, by passively straining food particles from water passing through their porous structures. They also lived in symbiosis with blue-green algae, which they would have fed upon as well.

This group successfully branched out into hundreds of different species, becoming a staple parts of shallow marine seafloor communities in tropical regions around the world. They formed large masses on top of their own accumulated remains, which helped form the first reefs in many areas. Thus, they created important marine habitats across the Lower Cambrian world that would have helped to nudge more familiar animals along their own evolutionary paths.

Within a mere 20–25 million years, by the Middle Cambrian, they had disappeared entirely. No one knows why, but it was likely due to competition with some new kind of browsing predator or better-adapted filter-feeding sponges or corals.

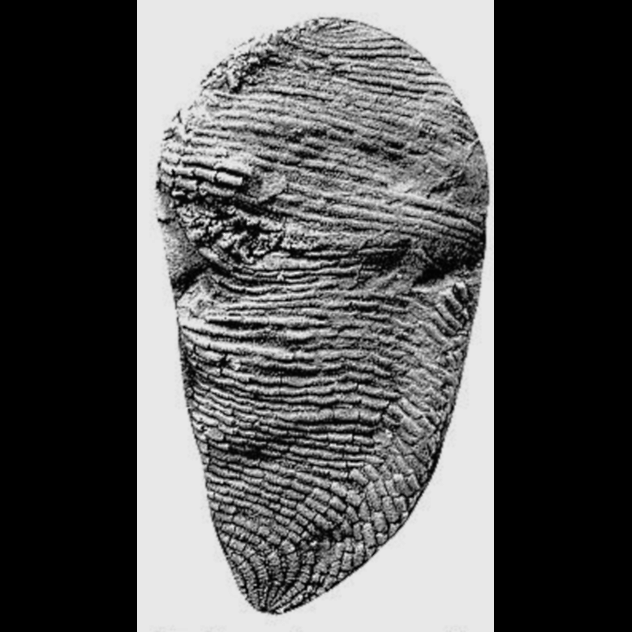

9 Helicoplacoids

The helicoplacoids are known only from the Lower Cambrian period, 525 million years ago. They were some of the first echinoderms, the group that includes modern-day starfishes and sea cucumbers. Helicoplacoids resembled tiny, 3- to 7-centimeter-long (1.2–2.8 in) armored footballs that could stretch and contract their bodies. They had bizarre feeding grooves which spiraled along the lengths of their bodies and were some of the first animals with skeletons.

They are believed to have lived upright in vertical mud burrows in the microbial mats that grew in the shallow, silty bays around Laurentia, the primeval continent that once spanned from British Columbia to California. They fed on plankton and organic detritus from the water above.

In geological terms, the helicoplacoids went extinct rather quickly, lasting only 15 million years. They didn’t survive past the Lower Cambrian. It’s possible that more mobile descendants succeeded them, which perhaps evolved into the starfishes, sea urchins, brittle stars, and sea cucumbers of today. Our contemporary understanding is that helicoplacoids were simply too specialized to life in soft, static mud fields and were unable to survive when burrowing animals evolved and proliferated, rendering their habitat much less dependable and severely altering its water currents.

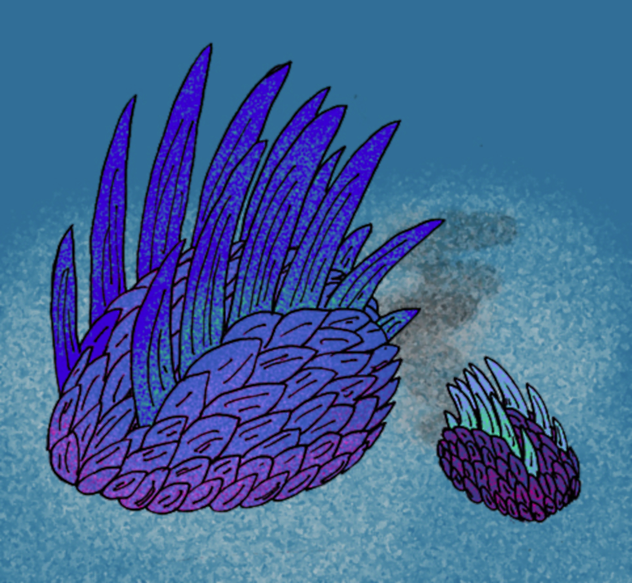

8 Halwaxiids

A particularly confusing array of soft but scale-armored animals arose in the Early Cambrian period, and they continue to perplex paleontologists to this day. This odd family of critters is tentatively believed to be an ancestral form of mollusc, perhaps an ancestor of today’s clams, squids, and snails.

The halwaxiids comprise the slug-like genus Wiwaxia and an associated worm-like genus called Halkieria as well as a handful of other isolated oddities. There is little concrete evidence to prove that these animals were related at all, as their characteristic armor plating could have evolved independently. An example of Wiwaxia is Wiwaxia corrugata, which was 5.5 centimeters (2.2 in) long and had two rows of long, blade-like defensive spines running down its back.

The halwaxiids didn’t survive past the Middle Cambrian (497 million years ago). Some scientists attribute their extinction to the decline of the bacterial seafloor mats upon which they fed, due to the proliferation of burrowing animals, which altered the stability of the Cambrian mud beds forever.

7 Dinocaridids

The dinocaridids, or “terror shrimp,” swam through the Cambrian seas about 515 million years ago. They were sight-based predators with some of the best eyes of any arthropods ever, and they lived in oceans around the world.

Dinocarids were veritable titans in the Cambrian seas. The 1-meter-long (3 ft) genus Anomalocaris had a bizarre whiskered mouth with two long feeding appendages. How exactly they fed continues to baffle scientists. It’s possible that they hunted tiny trilobite species, but it seems more likely that they drifted through the waters like a modern-day whale shark, filter feeding on plankton or browsing on soft-bodied worms.

Some groups indeed moved away from predatory hunting to become specialized filter feeders, harvesting plankton like a baleen whale and growing to immense sizes on this abundant diet. The largest found so far is Aegirocassis benmoulae, which reached 2.1 meters (7 ft) in length, making it one of the largest arthropods ever.

The 10-centmeter-long (4 in) Schinderhannes bartelsi, the last known dinocaridid, disappeared 390 million years ago during the Early Devonian. Perhaps the dinocaridids couldn’t handle increased competition from more modern predatory animals like squid and armored fishes, which became increasingly big players after the end of the Cambrian Period.

6 Blastozoans

The blastozoans represent a vast branch of primeval echinoderms that grew from elongated stalks, somewhat like modern-day sea lilies. They were one of the first forms of echinoderm, arising in the Early Cambrian. They were extremely successful, being much more common than helicoplacoids and other early echinoderms.

One of the most common Early Cambrian forms was the flower-like genus Gogia, which grew on archaeocyathid reefs and trilobite shells around Gondwana, an ancient supercontinent. Gogia was the tallest echinoderm of its day at 10 cenimeters (4 in). The genus was probably restricted in size by the loose, shifting, soupy mud of its time.

Blastozoans underwent a radical diversification over the Ordovician Period (490–434 million years ago), branching out into many kinds with highly diverse forms that became some of the most successful and characteristic animals of their age. Several kinds of blastozoan even made it through a horrendous global glaciation though only a single group would go on to survive until the Late Devonian mass extinction that was unleashed on Earth 70 million years later.

These last holdouts bore the adorably retro sci-fi name of “blastoids,” and they tenaciously clung to life until yet another epic catastrophe in the Permian Period nailed them once and for all. They died out 262 million years ago during the Capitanian Extinction, amid a major drop in global sea levels combined with severe oxygen depletion and marine acidification, the combined effects of which utterly devastated the world’s shallow water coastal habitats. Dr. David Bond of the University of Hull partly attributes the Capitanian Extinction to a massive volcanic eruption centered in Sichuan, China.

5 Homalozoans

The bizarre-looking homalozoans were another broad group of ancestral echinoderms, and many possessed odd, asymmetrical bodies. Homalozoans had flattened bodies with a single armored appendage of unknown function. IT may have been used for feeding, as an anchor to fix their bodies in sediment, or even as a flagella-like tail for swimming. In truth, we know nearly nothing about how homalozoans lived.

There are two recognized orders of homalozoan: The boot-shaped Cornutans first appeared in the Middle Cambrian Period. They were joined by the flattened, symmetrical Ankyroids in the Early Ordovician. The Ankyroids ultimately succeeded the Cornutans, surviving through the Ordovician glaciation and the subsequent mass extinction horrors of the Permian. They made it all the way to the Late Carboniferous Period (323–289 million years ago), though they gradually dwindled away in this epoch, becoming rarer and rarer until they disappeared altogether.

The homalozoans are another raft of divergent echinoderms from the Late Cambrian to Silurian periods that defy easy placement into existing classes and are represented by only a haphazard handful of specimens, some intermediate in form between the two groups and others isolated in structure from anything. Primeval echinoderms collectively yielded immense biodiversity and left a complex, calcareous jumble of bizarre fossils for future taxonomists to unravel.

4 Graptolites

The graptolites were marine superorganisms comprised of many microscopic animals that formed bushy, twig-like, branching colonies that mostly grew on the floor of the Cambrian oceans. Each component animal was connected to the others via a nerve cord.

As with the blastozoans, the Ordovician period proved to be a boom time for graptolites, which expanded and diversified into hundreds of new forms, including strange floating varieties that drifted near the ocean’s surface using inflated air sacs, filter feeding from the water column or attaching themselves to seaweed with filaments. They were some of the first complex multicellular life-forms to exploit the plankton-rich waters of the ocean’s surface as an ecological niche, which they did all over the world.

Over the next 24 million years, during the Silurian Period, graptolites began to decline, with all the floating types going extinct. Some paleontologists suggest that as fish became more and more common and successful, they proved to be too versatile and voracious predators for the graptolites to cope with, and they were subsequently grazed into oblivion.

The last few rare and isolated graptolite colonies on deep ocean seafloors died out 315 million years ago during the Late Carboniferous Period, alongside those poor, forgotten ankyroids. These sorry relics didn’t make it through the next glaciation period and subsequent major continental shifts, which drastically altered marine environments around the world yet again.

3 Edrioasteroids

Edrioasteroids are yet another massive grouping of extinct echinoderms. They vaguely resembled spineless sea urchins that were embedded onto substrates. The first known echinoderm Arkarua, was probably an edrioasteroid, living 600 million years ago in the Late Precambrian and growing 1 centimeter (0.4 in) wide. Edrioasteroids became big players in the Cambrian 15 million years later, though, encrusting soft seabed surfaces around most of the world’s continental coasts.

During the Ordovican, they, too, underwent a massive expansion, evolving to inhabit many different types of hard terrain, including shell pavements and reefs, as they were pushed out of most areas by competition from blastozoans and similar critters. After the Ordovician glaciation, a few varieties had managed to survive virtually unchanged since the Cambrian and were now easily the most primitive echinoderms alive. During the Carboniferous Period, surviving edrioasteroids grew 20 centimeters (8 in) tall and entered a phase of rapid evolution and specialization, free at last from competition with their age-old blastozoan rivals.

Sadly, as is a recurring theme here, this all amounted to very little in the broad scheme of things, when the edrioasteroids faced the full brunt of a worldwide holocaust called the Great Dying 251 million years ago, which smashed any survivor into so much kitty litter and erasing their divergent line of animal life forever in just 100,000 years.

The Great Dying was a catastrophe that made the dinosaur KT Extinction look like a bad day at the office, ending about 90 percent of all life in the oceans. Our own protomammalian ancestors somehow made it through, only to emerge into a strange new world. Science is still unsure about what caused the Great Dying, but a 2002 dig found evidence suggesting that a rock the size of Mount Everest struck Earth at this time, perhaps impacting in Australia, which would have contributed to the already horrendous oceanic acidification and deoxygenation as well as the continental shifts of the time.

God hates echinoderms.

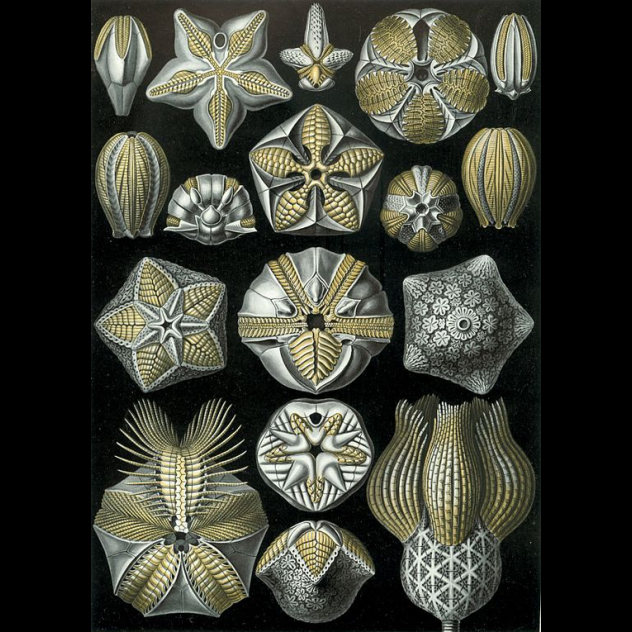

2 Trilobites

A much more familiar animal would meet the Grim Reaper’s scythe during the Great Dying, too—the trilobite. Their total diversity dwarfs that of any other group on this list, with more than 20,000 species so far known to science. They ranged in size from 2 millimeters to 70 centimeters (28 in). Trilobites first arose 521 million years ago, in the Cambrian, and would survive for nearly 300 million years. They lived in marine environments all around the world, where they occupied a broad swathe of different ecological roles, living variously as swimming plankton, crawling predators, and deep sea scavengers.

After their heyday in the Ordovician period, when they were the most common arthropods in the oceans, they entered a slow and inexorable decline as they weathered a series of one apocalypse after another after another. There was only a single trilobite order left by the Carboniferous Period. Due to a host of horrendous environmental and geological pressures unleashed upon the world’s dying oceans in the Permian, it was eventually whittled down to two families.

Nothing about trilobites made them particularly unfit for continued survival, but the Great Dying had all the warmth and tolerance of a junior high PE teacher. Their story is one of hopeless adversity in the face of incontrovertible misfortune and utterly inescapable cosmic cataclysm.

1 Conodonts

Conodonts arose in the Late Cambrian, 500 million years ago. Despite vaguely resembling fish, they are very much in a class of their own, as they never evolved proper backbones. These wormy, eel-like animals were extremely successful, living in oceanic waters around the world at different depths and temperatures. Most conodonts were tiny, with the largest varieties only reaching into the tens of centimeters in length. There are currently about 1,500 known species of conodont. Many were likely sluggish, bottom-dwelling scavengers, while others were adapted for more active, predatory roles.

Just like trilobites, conodonts were at their peak during the Ordovician before entering a long, slow decline that spanned many eons. Miraculously, some survived even longer than the trilobites, making it through the Great Dying and into the Triassic Period. The last conodonts died out 200 million years ago, during the Late Triassic. No one knows what happened to them for sure, as there was no single catastrophe associated with this time, but they probably declined due to ongoing sea level changes and frequent periods of oxygen depletion and exposure to geothermal chemicals. Just like the trilobites before them, the last survivors were whittled down by a never-ending run of environmental tragedies.

The very last conodonts to survive were deep-water animals called the gondollelids, which had degenerated to be as small, simple, and innocuous as they could possibly be. Inevitably, they, too, gave up the ghost for good.

Graham is still working at growing a real backbone. Email him at [email protected].