Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Fascinating Pre-Columbian Cultures

Thanks to the innate need of human beings to categorize things with seemingly arbitrary criteria and possibly some Eurocentric biases, the varied cultures of the Americas are divided by the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492. Having said that, here are 10 interesting pre-Columbian cultures.

10 Chimu Culture

Occupying much of the northern coast of Peru, the Chimu culture is believed to have arisen sometime in the 10th century AD. Possibly descended from small remnants of the Moche culture, which had flourished in the area centuries earlier, the Chimu built one of the most notable archaeological sites in all of South America: their capital city of Chan Chan, the largest pre-Columbian city on the continent. However, the former great city is now uninhabitable, thanks to a severe lack of water. (A vast network of canals supplied the Chimu people living there with their water.)

Though much of their culture was derived from their agricultural prowess, in no small part due to their ability to create irrigation marvels, the Chimu were also quite proficient with metalworking, specifically with gold and silver. Their pottery has a unique look, a shiny black finish which has been attributed to firing the clay at high temperatures within a closed kiln.

However, as was always the case with smaller cultures, the Chimu were eventually subsumed by their larger neighbor, the Incas. Between the years of 1465 and 1470, consecutive invasions by the great Incan king Pachacuti and his son Topa (aka Tupac) ended the independent rule of the Chimu and they eventually faded out of existence.

As for their religious beliefs, one of their most important deities was Si, the goddess of the Moon. Linked to the production and supply of food (as rainfall and the reproductive nature of the creatures of the sea were believed to be related to the Moon), she was presented with a number of different offerings, including human sacrifices. It was also a sharp contrast to a number of other early cultures, especially the Incas, because the worship of the Sun took a secondary role in the Chimu religion.

9 Hohokam Culture

With their name believed to have derived from the Pima word for “those who have vanished,” it’s no surprise that the Hohokam people are no longer with us. Having lived primarily in present-day Arizona, they first surfaced around AD 200, lasting over one millennium until their disappearance around the 15th century. Their existence is traditionally divided into four distinct periods of development: Pioneer (200–775), Colonial (775–975), Sedentary (975–1150), and Classic (1150–1450).

Like the Chimu of South America, the Hohokam were extremely skilled engineers when it came to irrigation. In fact, they were the greatest builders of canals in pre-Columbian North America. (Mormon pioneers used their canal system when they settled the area around Mesa, Arizona.) Thanks to that incredible skill, they were able to support a larger population than the hunter-gatherer tribes which were also active at the time.

Snaketown, a trading site located along the Gila River, was one of the largest villages the Hohokam people ever built and the first of their villages to be excavated. There, archaeologists uncovered one of the largest courts ever found on which Mesoamericans played the ball game for which they’re famous.

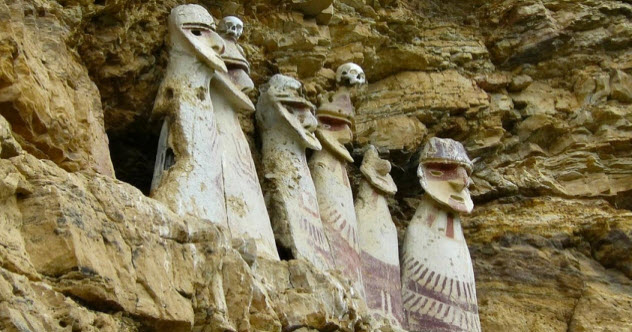

8 Chachapoya Culture

Described to Spanish conquistadors as the “cloud people” by their Incan conquerors, the Chachapoya of northern Peru thrived from about the eighth century AD until their subjugation at the hands of the Incan king Topa near the time of the Spanish arrival. Although the Chachapoya are lauded as fierce warriors and skilled builders, relatively little is known about their civilization.

One of the only sites to have been discovered, the ancient walled city of Kuelap was probably their capital and is the largest stone complex in South America, larger even than Machu Picchu. Kuelap’s construction is believed to have started sometime in the sixth century. Massive stone walls encircle the site, which measures 600 meters (2,000 ft) long and 110 meters (360 ft) wide. (Approximately 3,000 to 4,000 people are theorized to have inhabited Kuelap.)

Unlike many of their neighbors, the Chachapoya do not seem to have been particularly skilled with gold or silver because no artifacts containing those precious metals have yet been uncovered. However, they were incredibly skilled weavers and potters, with beautiful examples of textiles often surrounding their mummified dead.

Lastly, since nearly their entire population was decimated by diseases brought by the Spaniards (some estimates guess as much as 90 percent) and firsthand accounts are almost nonexistent, one of their characteristics has raised a lot of controversy. Spanish and Incan contemporaries described the Chachapoya as “white and tall,” leading some to theorize that they were descended from anyone from the Vikings to the lost tribes of Israel.

7 Huastec Civilization

Considered by many to be an offshoot of the Maya (though not necessarily from the Mayan civilization), the Huastec of northern Mexico seem to have sprung up around 1000 BC, although no one is completely sure. In fact, their origin myth is that the first of the Huastec people came by sea, settling in a place named Tamoanchan, although the exact location remains shrouded in the fog of history. This might help to explain why they were so adept at catching sea creatures, using large fishing nets and clay weights to help them.

One site we have located is called Tamtoc. It was first inhabited in 900 BC and remained in use until just before the 16th century AD. Located in the north-central region of Mexico, Tamtoc was one of the most important pre-Columbian urban centers, encompassing an area of more than 900 acres.

The most important discovery made at the site is Monument 32 (aka the Tamtoc calendar stone). Displaying complicated imagery believed to represent, among other things, the lunar cycle, the stone shows that their civilization had a firm grasp on astronomy. Known to their contemporaries as great farmers and traders, the Huastec remained independent for hundreds of years before they were conquered by the Aztecs in the 1300s. Later Spanish visitors observed that the Huastec generally didn’t wear clothing of any kind.

6 Canari Culture

Widely regarded as some of the fiercest fighters in the area, the Canari civilization existed in southern Ecuador from AD 500 to AD 1533 when they were taken over by the Inca Empire and its leader, Huayna Capac. Thanks to their heavy resistance, the Canari were punished severely by the Incas, who spread them out to more remote areas than any other tribe they conquered. In fact, just before the Spanish invasion, the Canari were castigated for their involvement, or lack thereof, in an Incan civil war. The victorious leader killed many Canari who were believed to have sided with the enemy.

However, once the Spanish invasion was in full swing, the Canari supported the conquistadors, helping them greatly during the siege of Cuzco in 1536–37. This eventually proved fruitless as less than 30 years later, Spanish records show no examples of preferential treatment given to the Canari over any other tribe.

As for their origin, it is distinctly non-Incan but not really known. Their origin myth involves their ancestors arising from a lagoon. Another point of interest about their mythology: The Canari, like a multitude of other cultures, had a flood myth. In their version, only two brothers survived, eventually finding a pair of parrots which brought them food and drink. One of the parrots was later captured, turning into a beautiful woman who became the ancestress of the Canari people.

5 Clovis Culture

Named for the New Mexico town in which evidence of their culture was first discovered, the Clovis people have been thought since the 1930s to be the progenitors of all Native American populations. This has since been proven by genetic evidence found in the only human skeleton associated with the Clovis culture, which was a small boy found in Montana. About 80 percent of the current Native American population can trace its origins to him.

Much of the evidence of the Clovis occupation of North America is based on what are called “Clovis points,” fluted projectiles made of a variety of stones, including jasper and obsidian. Dating to around 13,500 years old, their exact use, whether on spears or darts, has not been determined.

The “Clovis first” theory has fallen out of favor with many scientists because evidence of the existence of multiple cultures predating the Clovis by hundreds of years has since been discovered. However, one point must be made: There is no DNA evidence to suggest the earlier peoples are genetically different than the Clovis culture, just that there was at least one migration before what is traditionally known as the Clovis migration. Additionally, even though the fluted projectiles found at the older sites are different than those made by the Clovis culture, it could simply be the evolution of technology at work.

4 Taino Civilization

When Columbus arrived in 1492, the Taino people were the first he encountered. At the time of his arrival, they were the dominant civilization in a number of Central American countries, including Cuba, Jamaica, and, of course, Hispaniola. On the island of Hispaniola, some scholars estimate that the native Taino population might have reached as high as three million people, although one million is more likely. Some believe that the entire civilization numbered as high as three to six million.

As for their culture, the Taino never developed a written language of their own, although they were quite accomplished in a number of different areas. However, various Taino words eventually entered the world lexicon, including their words for “barbecue,” “hammock,” “tobacco,” and “cannibal.”

Their pottery was exquisite, but to their eventual detriment, they were extremely generous. Columbus later wrote about them: “They will give all that they do possess for anything that is given to them, exchanging things even for bits of broken crockery. [ . . . ] They should be good servants.”

Unfortunately, the fate which befell the Taino people was all too common among Native American populations. Within 50 years, very little of their civilization existed, with many of them succumbing to disease, starvation, and slavery. Some estimates of their decimation range as high as 85 percent. Many of the women ended up marrying the conquistadors who enslaved them, creating a new mestizo people from which some claim to be descended today.

3 Mixtec Civilization

Thanks in large part to the lucky preservation of many of their codices, the Mixtec civilization is one of the best understood of the pre-Columbian cultures. With a political system reminiscent of ancient Greece, the Mixtec did not have a centralized capital as many of the other cultures possessed.

The Mixtec civilization consisted of a number of city-states, each governed by its own king. If there was such a thing as a capital for the Mixtec, it would probably have been Tilantongo, a site of extensive ruins. Their cities were also highly socially stratified, with kingship passing down through familial connections and a working class and servant class which mostly worked for the benefit of the elite.

Existing even to this day in the Oaxaca Valley of southern Mexico, the Mixtec culture first developed in AD 600. Its eventual demise as an independent nation occurred in the late 15th and 16th centuries at the hands of either the Aztecs or the Spanish.

Their artistic ability was renowned by their neighboring tribes, and they were active traders, having developed a knack for metalwork and creating turquoise jewelry. Their writing system can best be described as pictographic, with the Vienna Codex as one of the most famous of them all, containing painted pictures on deerskin.

Eight Deer Jaguar Claw, a notable ruler in the 11th century, contributed the most to the expansion of the Mixtec civilization. The Codex Zouche-Nuttall stated that he conquered a number of cities until he was sacrificed for trying to set up a monarchy-like form of government for the civilization.

2 Tarascan State

Archaeological evidence has shown that sometime in the 13th century, a rather large group of people moved into what is present-day Michoacan, a state in western Mexico. Warrior-like in nature, they dominated the inhabitants of the area, eventually establishing their own complex system of governance: a collection of city-states controlled by a centralized king. Later expansions of their territory were won through the dominance of their professional armies, which enabled them to defeat the Aztecs in various wars around the end of the 15th century.

After the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan was captured by Hernan Cortes in 1521, the Spanish turned their sights on Tarascan territory after hearing rumors about untapped gold and silver deposits in the area. For nearly a decade, the Tarascan people, under the rule of Tangaxuan II, paid tribute to the Spanish and lived in relative peace with their invaders.

However, that all changed in 1530 with the murder of their leader. In the decades that followed, warfare, slavery, and disease ravaged the population, with unrest lasting until a Spanish bishop named Vasco de Quiroga began to address some of their issues and gained their friendship.

As for their culture and way of life, the Tarascan people were curious examples in that they didn’t trade much with their neighbors. In fact, very little evidence has been found showing any exchanges taking place between the Tarascan state and the Aztec Empire. However, this may be explained by the vast amount of land and luxury resources controlled by the Tarascans, making trade a pointless exercise for them.

In addition, much of their culture was similar to other Mesoamerican cultures, although they never developed a writing system or a sophisticated calendar system. Ceramic pottery was their strong suit, though, with the Spanish even writing about their skills as craftsmen.

1 Totonac Civilization

The first natives to greet Cortes when he landed in Mexico, the Totonac had just been made a tributary of the Aztec Empire. Generations of men had fought in battles against them, but they were finally defeated and quickly grew tired of it.

Like a handful of other tribes, the Totonac saw Cortes as a way to free themselves from Aztec tyranny once and for all, so they threw their allegiance behind the Spanish. In addition, the Totonac was one of the earliest civilizations to begin converting to Christianity as Cortes was disgusted by human sacrifice and sought to convert the natives as soon as possible.

Though they were safe from war at the hands of the Spanish, the Totonac still succumbed to the diseases which were brought over and their population was decimated. However, thousands of them survived. Their descendants still live mainly around the towns of Puebla and Veracruz in southern Mexico. The influence of the Totonac civilization is still felt as some scholars believe they were the builders behind some of the greatest Mesoamerican cities, including Teotihuacan and El Tajin.