History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Recent Archaeological Finds That Rewrite History

Every year, our knowledge of the past improves a little bit. 2016 has been no different. Scientists have made several discoveries and revelations which have helped us better understand (and, in some cases, drastically altered) our history.

10 Ancient Chinese Beer

We’ve known for a while that the ancient Chinese enjoyed a drink due to evidence of fermented beverages derived from rice found at a 9,000-year-old site in the Henan Province. However, in 2016, we learned that the Chinese were also beer lovers. Archaeologists excavating the Shaanxi Province found beer-making equipment dating to 3400–2900 BC.

This marks the first direct evidence of beer being made on-site in China. Residue found in the vessels also revealed the ingredients of the ancient beer, including broomcorn millet, lily, a grain called Job’s tears, and barley.

The presence of barley was especially surprising as it pushed back the arrival of the crop in China by 1,000 years. According to current evidence, the ancient Chinese used barley for beer centuries before using it for food.

9 A Man And His Dog

Dogs were man’s best friend 7,000 years ago according to evidence found at Blick Mead near Stonehenge. Archaeologist David Jacques found a dog’s tooth that belonged to an animal originally from an area known today as the Vale of York.

The dog served as a companion to a Mesolithic hunter-gatherer. The two undertook a 400-kilometer (250 mi) trip from York to Wiltshire which is now considered the oldest known journey in British history. Jacques argued that the dog was domesticated, part of a human tribe, and most likely used for hunting.

Durham University later confirmed his findings through isotope analysis performed on the tooth enamel. It showed that the dog drank from water in the Vale of York area. They also believe that the dog would have looked similar to a modern Alsatian with wolflike features.

8 King Tut’s Extraterrestrial Dagger

In mid-2016, scientists were able to wrap up a mystery that had been puzzling archaeologists since Howard Carter found King Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922. Among the many items buried with the young pharaoh was a dagger made of iron. This was unusual as ironwork in Egypt 3,300 years ago was incredibly rare and the dagger had not rusted.

An examination with an X-ray fluorescence spectrometer revealed that the metal used for the dagger was of extraterrestrial origin. The high levels of cobalt and nickel matched that of known meteorites recovered from the Red Sea.

Another iron artifact from ancient Egypt was tested in 2013 and was also made using meteorite fragments. Archaeologists suspected this outcome due to ancient texts referencing “iron of the sky.” Now they believe that other items recovered from the pharaoh’s tomb were also made using meteorite iron.

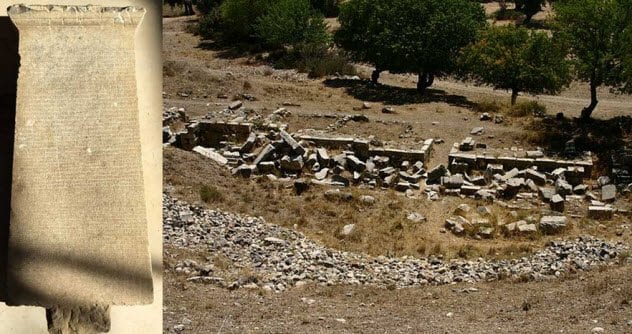

7 Greek Bureaucracy

The ancient city of Teos in modern-day Turkey has been an archaeological boon as hundreds of steles were recovered from the site. One remarkably intact stele features 58 legible lines that represent a 2,200-year-old rental agreement. It shows us that bureaucracy was just as much a part of ancient Greek society as it is today.

The document describes a group of gymnasium students who inherited a piece of land (complete with buildings, altar, and slaves) and then rented it at auction. The official document also mentions a guarantor (in this case, the renter’s father) and witnesses from the city’s administration.

The owners retained the privilege of using the land three days a year as well as annual inspections to ensure that the renters didn’t damage the property. In fact, half the agreement deals with various punishments for damages or not paying rent on time.

6 Neanderthal STDs

A few years ago when scientists mapped out the human genome, they were surprised to discover that we have about 4 percent Neanderthal DNA due to cross-species breeding. However, our ancestors got something else from their Neanderthal cousins—a primitive version of the human papillomavirus (HPV).

Through statistical modeling, scientists were able to recreate the evolutionary steps of the HPV16 virus. When modern humans and Neanderthals split into different species, the virus also split into two distinct strains.

Initially, the HPV16A virus was only carried by Neanderthals and Denisovans. When humans migrated out of Africa, they only carried the B, C, and D strains.

However, when they reached Europe and Asia and started having sex with Neanderthals, they gained the HPV16A strain, too. Further study into our genetic history could explain why the virus can cause cancer in some people but clear right up for others.

5 Unearthing A Dead Language

Even though it hasn’t been used for almost 2,000 years, Etruscan remains one of the most intriguing dead languages. It had a large influence on Latin which, in turn, influenced many European languages we still speak today. However, samples of Etruscan texts of any significant length are few and far between. Even so, in 2016, archaeologists uncovered a 1.2-meter (4 ft) stele inscribed in Etruscan.

The 2,500-year-old stone slab was found while excavating a temple in Tuscany. It was well-preserved because it was reused as a foundation for the temple. Coincidentally, one other major Etruscan artifact, the Linen Book of Zagreb, also was preserved by being repurposed as mummy wrappings.

Despite its condition, the stele still featured chips and abrasions. So scholars want to clean and preserve it thoroughly before attempting to read it. They suspect that the text is religious and will provide us with new insight into the Etruscan religion.

4 The Elusive Higgs Bison

This year, a new animal species was discovered using a unique method—ancient cave art. Researchers studied paintings from caves in Lascaux and Pergouset and noticed several changes between the bison painted 20,000 years ago and the ones painted 5,000 years later. The changes included different body types and different horns.

While the earlier paintings were reminiscent of the steppe bison, scientists believed that the newer drawings depicted an entirely different species. To confirm their hypothesis, they examined DNA evidence from bison bones and teeth that were recovered from numerous sites across Europe.

These bones and teeth originated between 22,000 and 12,000 years ago. The scientists concluded that, indeed, the later bison was a new species descending from the steppe bison and the aurochs.

The new revelation ends a decade of confusion regarding the sequencing of the steppe bison genome which sometimes had sections out of place. The newly found elusive species has been named the Higgs bison.

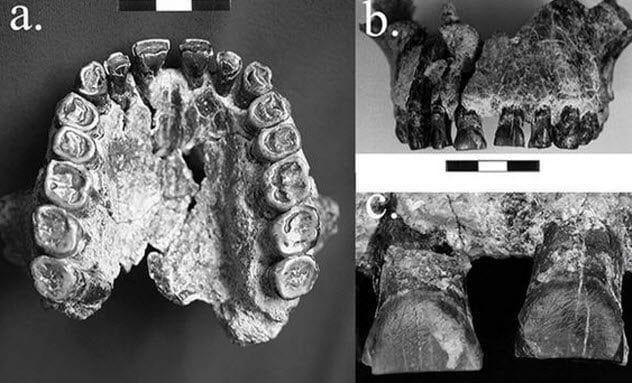

3 First Right-Handed People

A new study in the Journal of Human Evolution gives proof of the first recorded instance of right-handedness in hominins—and it’s not for Homo sapiens. Paleoanthropologist David Frayer has found evidence of this phenomenon in Homo habilis from 1.8 million years ago.

The study looked at teeth fossils from Homo habilis and found scrapes that were indicative of right-handed tool use. Frayer and his team tried to recreate the hominins’ behavior. Modern subjects would hold meat with their mouths and left hands while using their right hands to tear away flesh using stone tools. Scratches left on mouth guards were similar to those found on the fossils.

While not everyone agrees with Frayer’s methods, more significant here is the mere existence of hand dominance in Homo habilis. This trait is still poorly understood in modern humans, and it seems to be much older than we previously thought. Further study might help to explain this phenomenon and provide new insight into the evolution of the human brain.

2 Humanity’s New Mystery Ancestor

New discoveries made on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi suggest that it might have once been inhabited by an as-yet-undetermined hominin. Archaeologists have uncovered hundreds of stone tools which are at least 118,000 years old. However, all evidence indicates that modern humans first set foot on the island between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago.

The existence of a new species of hominin is very plausible. Sulawesi is located near the island of Flores. In 2003, archaeologists found another hominin there called Homo floresiensis (the so-called “hobbits”) which evolved independently on the island before going extinct 50,000 years ago.

Perhaps it is a new ancestor in our evolutionary timeline. Or maybe Homo floresiensis somehow made its way to the neighboring island. Or humans reached Sulawesi much earlier than we think. Archaeologists are now digging for fossils that would enable them to know for sure.

1 The Cannabis Road

Current thinking says that ancient China was the place where cannabis was first used and perhaps cultivated as a crop around 10,000 years ago. However, the Free University of Berlin recently compiled a database of all available archaeological evidence of cannabis that showed Eastern Europe and Japan developing cannabis usage around the same time as China.

Moreover, cannabis use throughout Western Eurasia remains consistent throughout the years while the record is spotty in China until it intensifies in the Bronze Age. Scholars speculate that cannabis had become a tradable commodity by this time and spread throughout Eurasia using a trade network akin to the iconic Silk Road.

The hypothesis is backed up by other crops like wheat that also became more widely available around the same time. Scholars even identified the nomadic Yamnaya culture as the possible ancient dope dealers who, according to DNA studies, traveled this route at that time.