History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Daring Explorers Who Changed The Medieval World

From Columbus to Magellan, the famous travelers of the Age of Exploration have become household names. Before that, we tend to think of the world as a parochial place, with people barely aware of what lay beyond their own backyard. But the truth is that daring explorers flourished in the Middle Ages, crossing vast distances and changing how Medieval people thought about the world.

10Friar Julian

Around 895 A.D., the Hungarians swept out of Eastern Europe, raiding across Europe and establishing themselves firmly in the Carpathian Basin. But they always remembered their distant homeland somewhere across the mountains. In particular, they mourned the Hungarians who had been split from the main group by a Pecheneg attack and left behind before the great migration into Europe. In 1235, King Bela of Hungary asked four Dominican friars to travel east in search of the missing Hungarians and their lost homeland.

Of the four explorers, only a friar named Julian survived the whole journey. He wrote that they had started their search around the Crimea, before trekking across the Caucasus and journeying up the Volga River. According to Julian, he found the Eastern Hungarians living there in a region he called Magna Hungaria (“Great Hungary”). However, by this time Julian had realized that a great threat was brewing. The Mongols were invading Russia and Julian correctly feared that this invincible new force would soon reach Hungary. He hastened back to Europe, where he provided the first detailed warning of the Mongol approach, and the Eastern Hungarians once again passed out of the history books.

9Gunnbjorn Ulfsson

It is fairly well-known that Erik the Red was the first Viking to sail to Greenland and settle there. But Erik did not actually discover Greenland. That honor goes to his relative Gunnbjorn Ulfsson, who reported the existence of a land west of Iceland in the early 10th century.

According to the sagas, Gunnbjorn was sailing to Iceland when he was blown off course by a storm. He reported seeing some skerries (small, uninhabitable islands) rising from the sea to the west and deduced that a larger landmass must lie beyond them. However, modern historians believe that Gunnbjorn was actually seeing the “hillingar,” a well-known mirage caused by “optical ducting” off the Greenland coast.

In any case, Gunnbjorn was right to suspect that a large island lay beyond whatever he saw. This new land was eventually settled by Erik the Red and used by his son Leif as a launch point for his famous voyages to the Americas.

8Rabban Bar Sauma

Often called the Marco Polo of the East, Rabban bar Sauma was born in China in 1220 A.D., not far from modern Beijing. He became a Nestorian Christian monk and became known for his fervent acts of devotion. He eventually decided to undertake a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, requiring him to trek across the Asian landmass. He eventually made it to Baghdad, but a war in the Holy Land meant he could not journey on to Jerusalem.

After a few years in an Armenian monastery, the Mongol ruler of Iran asked Rabban to undertake a diplomatic mission to Europe. The fearless monk was feted in Constantinople and narrowly wriggled out of a difficult situation in Rome, where some cardinals suspected that he was a heretic. He stayed with King Philip of France and made it to the Atlantic Ocean near Bordeaux, where he met with King Edward “Longshanks” of England.

After returning to Persia in triumph, Rabban retired to found a monastery in Azerbaijan. He carefully kept a diary of his travels, providing modern historians with a fascinating outsider’s perspective on Medieval Europe.

7William of Rubruck

After the initial Mongol invasion of Europe, the European powers would send several ambassadors on the long journey to the court of the Great Khan. By far the most insightful was the monk William of Rubruck, who actually was not an ambassador at all and mostly wound up in Mongolia by accident.

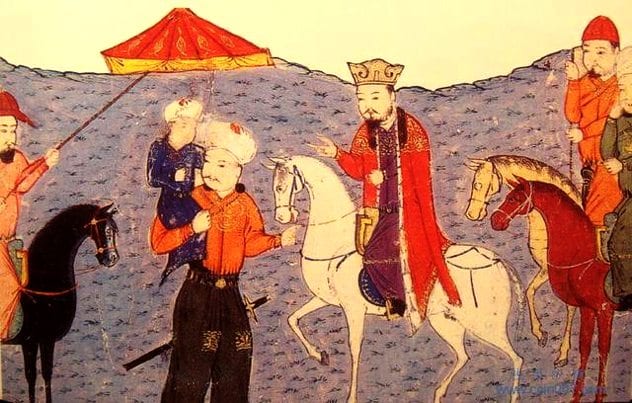

During the Seventh Crusade, William asked King Louis XI of France for permission to travel from Palestine to modern Russia, where he hoped to minister to the Christians enslaved by the Mongols during their attack on Hungary a decade earlier. But when he rocked up in Russia, the Mongols completely misunderstood his mission and assumed he was a formal ambassador. As such, they sent him on to the court of Mongke Khan in Mongolia.

William was in no position to argue and found himself swept along to Karakorum, where he spoke with Mongke and participated in a formal debate between Christians, Muslims, and Buddhists (everyone ended up blackout drunk before Mongke got around to picking the winner).

He returned to France around 1255, where he wrote a detailed and often humorous account of his travels (a highlight is a lengthy religious discussion with some Buddhists which suddenly ends because “my interpreter was tired and . . . made me stop talking). Among other breakthroughs, he alerted Medieval Europe to the existence of Buddhism and persuaded mapmakers that the Caspian Sea was landlocked.

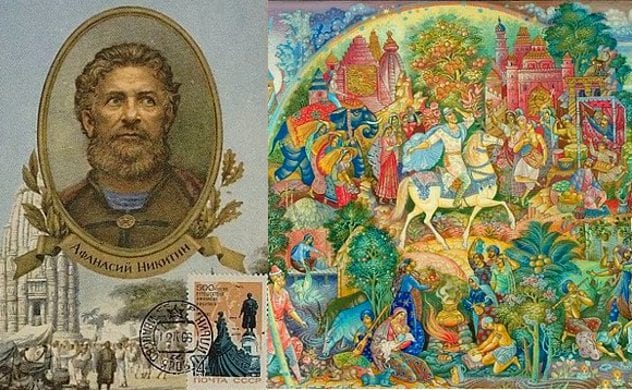

6Afanasy Nikitin

Afanasy Nikitin was a merchant from Tver who became arguably the greatest Russian explorer of the Medieval period. He initially left Tver in 1466 on a trading expedition to the Caucasus but was attacked and robbed on the Volga. With his finances in ruins, he decided to seek opportunities further afield and traveled on through Persia to Hormuz, where he took ship for India.

Nikitin arrived in India in 1469. At that time, the country was virtually unknown in Russia, but he fit in well and traveled widely through the Deccan. He found he got along better with the local Hindus than their Muslim rulers, who kept trying to talk him into converting. He wrote extensive descriptions of the local temples and religious practices and made visits to Calicut and Sri Lanka, where he described the famous Adam’s Peak as a holy site for Hindus, Buddhists, Christians, and Muslims.

In 1472, Nikitin became homesick and decided to make the journey back to Tver. Along the way, he visited Ethiopia and Oman, but he sadly died in Smolensk, Russia, just a short distance from his beloved Tver.

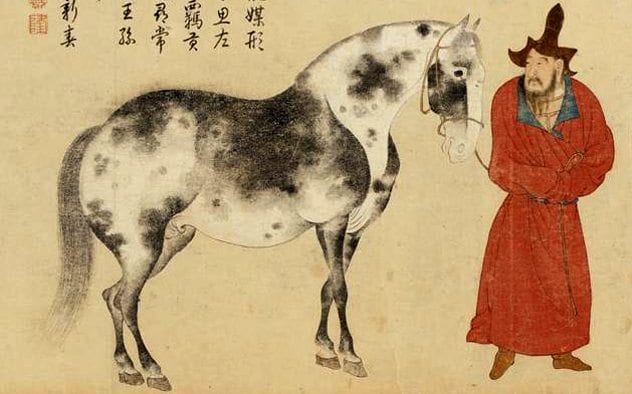

5Li Da and Chen Cheng

Li Da and Chen Cheng were two Chinese eunuchs who undertook a dangerous expedition through Central Asia in the 1410s. Li Da was by far the more experienced traveler, having already made two trips into the heart of Asia. But he did not write about them, so he has been almost forgotten. But Chen Cheng did keep a detailed diary, so he gets all the glory, although he was always subordinate to Li Da.

The two eunuchs set out in 1414, on a diplomatic mission for the Yongle Emperor. They journeyed through a desert for 50 days, then navigated the barren terrain of the world’s second lowest depression, and clambered past the Tian Shan mountains. They waded through salt marshes and lost most of their horses crossing the Syr River. Finally, after 269 days, they reached Herat, presented their gifts to the sultan and went home. Astonishingly, Li Da would make the same journey twice more, always making it through without a scratch.

4Odoric of Pordenone

Beginning in the late 13th century, the Franciscan monks began a determined effort to establish a presence in east Asia. They sent out missionaries like John of Montecorvino, who became the first Catholic Bishop of Peking (Beijing), and Giovanni de’ Marignolli, who journeyed widely through China and India. Perhaps the best traveled of all was Odoric of Pordenone, a Franciscan of Czech extraction who set out for the east around 1316.

After some time in Persia, Odoric preached throughout India before taking ship for modern Indonesia, where he visited Java, Sumatra, and possibly Borneo. Arriving in China, he based himself in Beijing but continued to travel widely (he was particularly impressed with Hangzhou) for the next three years. He then decided to return home via Lhasa, Tibet.

After returning to Italy, he dictated his biography from his sickbed (which may explain why they abruptly end after Tibet). He died in Udine in 1331. His memoirs became enormously influential—but not in the way he might have hoped. An unknown hack rewrote them to add all sorts of ludicrous events and fantastical beasts and published them as “The Travels Of Sir John Mandeville,” which became a smash medieval bestseller.

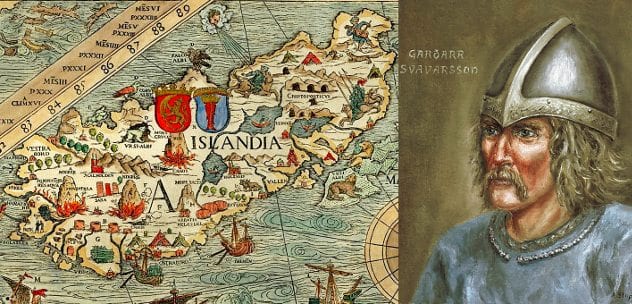

3Naddodd and Gardar

According to the saga of Ari the Wise, the first Viking to discover Iceland was a settler in the Faroe Islands called Naddodd, who was blown off course by a storm to a place he called “Snowland.” This accidental discovery was followed up by a Swede named Gardar Svarsson, who explored the coast of the island and wintered there before sailing back to Scandinavia, full of praise for the new land. Thanks to Gardar’s daring and Naddodd’s ability not to die in a storm, the Vikings would quickly settle in Iceland, where their descendants remain to this day.

Oddly, the sagas insist that Noddodd and Gardar were not the first Europeans to reach Iceland. According to Ari, Scottish or Irish monks known as Papar were already living as hermits in Iceland when the Norse arrived, but they quickly left as “they did not want to share the land with heathens,” leaving behind “Irish books.” Of course, Ari was writing 250 years later, and supporting evidence for the Papar’s existence is thin, so use your best judgment there.

2Benjamin of Tudela

Very little is known about Benjamin of Tudela since his travelogue remains the only source for his life. He was a Jew who set out from Tudela in Spain around 1160 and kept a careful record of his travels. After journeying through Barcelona and southern France, he spent some time in Rome before traveling south through Greece to Constantinople.

From Constantinople, he took ship for the Holy Land and journeyed through Palestine and Syria to Baghdad and Persia. His writings then describe Sri Lanka and China, but the descriptions become fantastical, and most historians believe he did not make it farther than the Persian Gulf.

Benjamin’s primary value to historians was his focus on the Jewish communities he encountered everywhere on his travels, which tended to be ignored by later travelers. His writing remains the best travelogue of this hidden Medieval world.

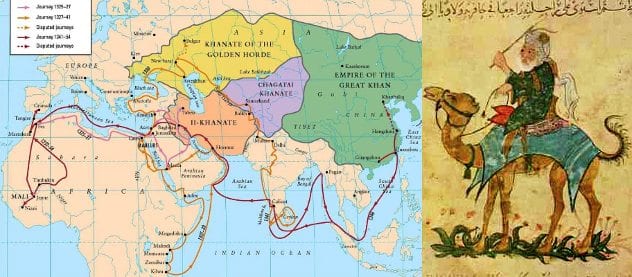

1Ibn Battutah

It is impossible to write about medieval travelers without mentioning Ibn Battutah, the greatest traveler of his age and arguably of all time. While most medieval explorers journeyed for trade, diplomacy, or religion, Ibn Battutah simply loved traveling: he was a natural tourist. As a result, it has been seriously suggested that he covered more miles than anyone else until the invention of the steam engine.

Born into a wealthy Moroccan family, Ibn Battutah was sent on a pilgrimage to Mecca as a youth. It was supposed to prepare him for a career as an Islamic judge, but instead, it awakened his wanderlust. Instead of returning home, he crisscrossed the Middle East and then sailed down the East African coast to modern Tanzania.

Running low on funds, Ibn Battutah then decided to journey to Delhi, where he had heard the sultan was extremely generous. Typically, he went via Turkey, Crimea, Constantinople, and the Volga River in what is now Russia. Finally, he reached Afghanistan and crossed the Hindu Kush into India, where the sultan showered him with gifts and sent him on a diplomatic mission to China.

Unfortunately, he was robbed, caught in a war, and shipwrecked (in that order), losing all the gifts the sultan had asked him to present to the Chinese court. Too afraid to return to Delhi, he spent a few years hiding out in the Maldives, then visited Sri Lanka, Bengal, and Sumatra, before finally making it to China around 1345.

Returning to the Middle East two years later, he found the region ravaged by the black plague and quickly returned to Morocco. After a quick jaunt to Spain, he embarked on his last great journey, crossing the Sahara and exploring the Malian Empire. In 1353, he returned to Morocco, wrote his memoirs, and promptly vanished from history.