History

History  History

History  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

10 Incredible Accomplishments That Ruined Their Creator’s Lives

As the great philosopher Rodney Dangerfield pointed out, some people “get no respect.” One would think after inventing a permanent part of pop culture for generations, one might finally be entitled to some respect. Even that’s not true. In fact, as these following 10 people show, sometimes one only gets properly celebrated after having their entire life destroyed.

SEE ALSO: Top 10 Things Americans Get Wrong About Their Own History

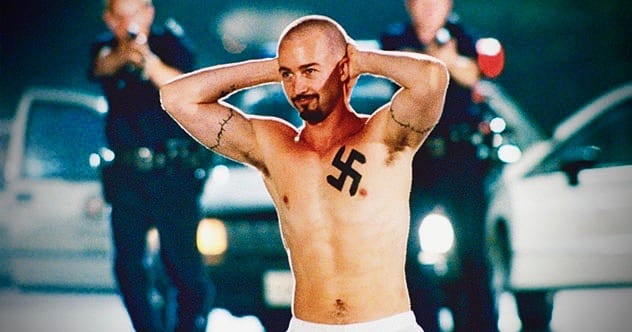

10 Tony Kaye Went Down in American History X

Tony Kaye has good ideas. Most of them have nothing to do with American History X though. Previously known for directing music videos, American History X was Kaye’s chance to become a household star. The resulting film was a lauded triumph. The movie’s dark and mature tale of the glorification of violence led to cartoonish antics off screen.

The Oscar nominated finished product was unrecognizable from Kaye’s original vision. The first edit barely clocked in at 95 minutes. New Line Cinema insisted he recut. Kaye refused. To stretch out the run time and emotional weight, Edward Norton secretly inserted more clips of his performance. Kaye felt so betrayed he ordered his name be taken off the credits and replaced with the pseudonym “Humpty Dumpty”. Obviously not wanting their deft look on neo-Nazism to be associated with a clumsy egg, New Line kicked Kaye out. Accompanied by a priest, a rabbi, and a Tibetan monk, Kaye barged into the office demanding to be brought back on board. Sounding like a literal joke, the studio denied his request.

To besmirch the movie’s reputation, Kaye published full-page ads insulting Norton and the studio. Financially ruining himself, the 35 ads cost Kaye nearly 1 million dollars. Persona non grata in Hollywood, Kaye’s filmography afterwards is a scattershot collection of half-finished projects and moments of genius. 20 years later, Tony Kaye has never made a movie as celebrated as American History X. Because of American History X, he never will again.[1]

9 Napoleon Dynamite Blew Up in Efren Ramirez’s Face

Power corrupts. Absolute power corrupts absolutely. The power of a fictional school president in a bizarre indie flick from 2004 corrupts bizarrely. Efren Ramirez has found moderate success over the years with the quirky movie Napoleon Dynamite and its short lived animated spinoff. He will always be most recognized as Pedro Sanchez, even if a lot of people cannot recognize Efren Ramirez.

Everything about Napoleon Dynamite’s success was unlikely. However, the most statistically improbable thing about the movie is that both of the main protagonists are sets of identical twins. Jon Heder and his brother Dan remained close during Napoeleon’s height. Efren and Carlos did not.

Wanting to cash in on the fame, Carlos crashed public appearances by posing as his brother. Likely overestimating the frequency of necessary Pedro sightings, Carlos says Efren sanctioned these hijinks when Efren was too busy to attend himself. Carlos has confessed that on at least one occasion he attended without Efren’s knowledge, “to get back at him for a personal matter which involved the girl I was dating at the time.” Neither Carlos or Efren have specified what Carlos meant by that. Luckily thanks to Napoleon Dynamite, Efren has a history of dealing with love triangles.

Efren’s subsequent behavior discounts Carlos theory that this was all in jest. Threatening to sue, Efren issued a cease-and-desist order. Carlos had to pay a 10 million dollar fine if he ever impersonated Pedro again. A rift enveloped the twins. Citing “the magnitude of Napoleon Dynamite and everything that has come along with it,” Carlos says the movie has ruined his life. The two have yet to reconcile.[2]

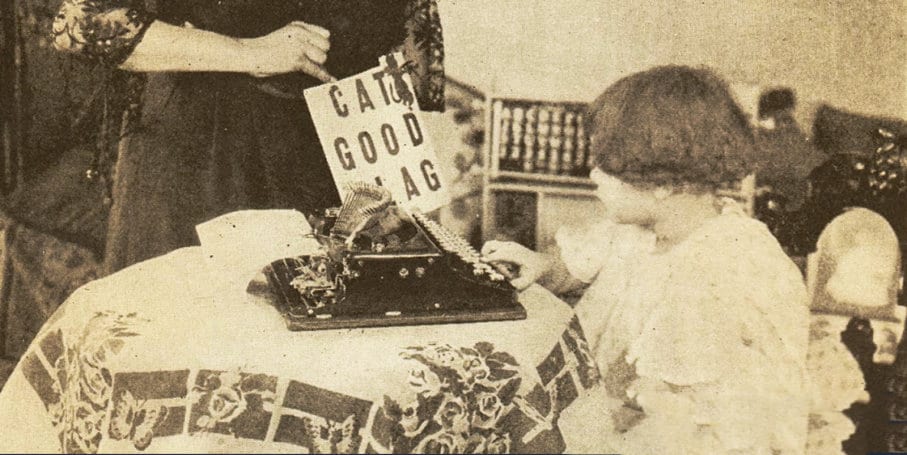

8 Winifred Sackville Stoner Got No Poetic Justice

It is probably the first thing taught in United States History class, even if the author never is. Kindergartners can easily remember the dawn of European expansion in the Americas with the handy mnemonic “In fourteen hundred ninety-two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue”. Winifred Sackville Stoner Jr would hate that people are still quoting her works. Her mother would love it.

Winifried Sackville Stoner Sr was more than your typical stage mom. Fluent in Esperanto, Winifred Stoner Sr. was convinced that the universal language was the best way to educate children. Paraded around the country, Stoner Sr trumpeted Stoner Jr as a child genius. It was hard to disagree. Remarkably, Stoner Jr was talking at one years old, writing at two, and typing at three. Like a lot of details about her prodigy years, Stoner Sr likely exaggerated some facts. Either way, her mother felt vindicated when Stoner Jr’s 1913 poem “History of the United States” earned the 12-year-old child acclaim.

Grown out of childhood, Stoner renounced her years as a prodigy, including her poetry. Looking back on her time in the spotlight, Stoner says her mother’s experiment damaged her for life. Isolated as a prodigy, Stoner rebelled by going through a series of terrible relationships. Her first disastrous marriage was to the 35-year-old French count, Charles de Bruche. Before Stoner Jr could divorce de Bruche, he supposedly died in a car accident in Mexico City. Her four other marriages were equally doomed, including an engagement to Woodrow Wilson’s former Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby, a man more than twice her age. After faking his death, Charles de Bruche returned to try and blackmail Stoner as a bigamist. He had tried similar cons across Europe. For 50 years, she secluded herself from the public and marriage. In nineteen hundred eighty three, Stoner Jr. died lonely.[3]

7 Philo Farnsworth Had Plenty of Reason to Hate Television

It took a lot of work to invent the greatest tool of laziness. Primitive cumbersome television models existed for years before Philo Farnsworth perfected the technology. Drudging up dirt on the gridlike pattern of his ranch, Farnsworth had a major breakthrough. By scanning an image line by line, one could broadcast a clear picture onto any screen. This idea was the literal groundwork for the 1927 “Television System” patent.

Four years earlier, Vladimir Zworykin patented a similar system. The key difference was that Zworykin’s machine did not work. That hitch did not bother David Sarnoff, head of radio behemoth RCA. Fearful of television’s competition to radio, Sarnoff tried to buy out Farnsworth’s superior technology. The Mormon farmer turned down the proposal. Sarnoff went to war. While suing Farnsworth for patent violation, Zworykin and Sarnoff sent spies to monitor him. Subterfuge was not far enough, so they simply released a line of TVs anyway without Farnsworth’s permission. RCA lost the suit and had to acknowledge Farnsworth owned the rights to the patent. It was a short lived victory. His patent expired in the mid40’s, missing television’s explosion by mere months.

After struggling for decades, he could finally relax and enjoy his invention. With a television in every home, he dreamed that people would “learn about each other.” His utopian vision turned to static. Viewing westerns and gameshows convinced him he “created kind of a monster, a way for people to waste a lot of their lives.” Farnsworth did not have much more life to waste. Stress from his squandered fortune caused a fatal bout of pneumonia. He was 64.[4]

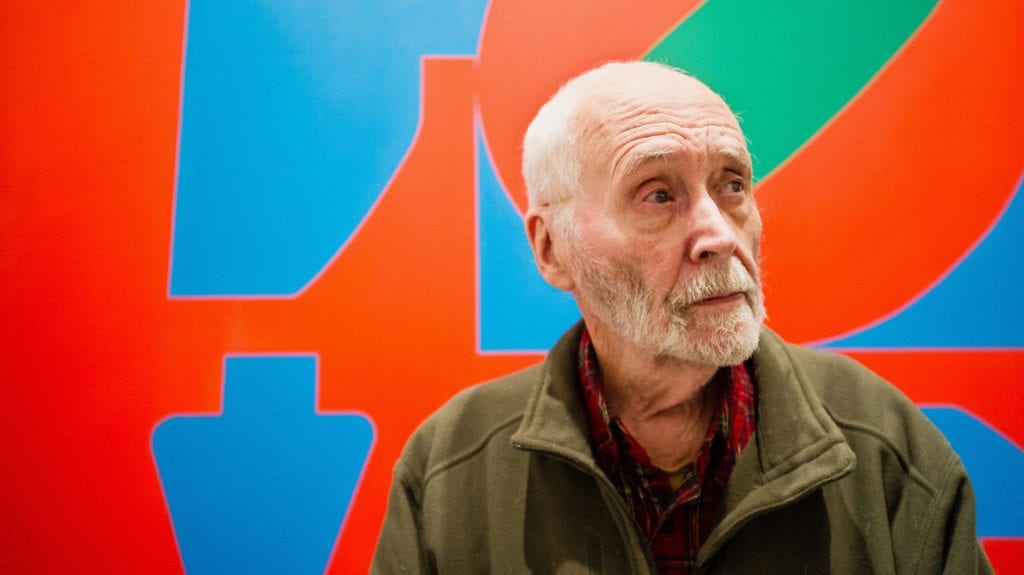

6 Robert Indiana Does Not Love “LOVE”

The simplest ideas are often the most popular. Perhaps no idea is simpler than LOVE. Robert Indiana’s iconic sculpture depicts a L supporting a leaning O stacked on top of a V and E. Like plenty of people, Robert Indiana feelings toward LOVE is complicated.

During the 1960s, Robert Indiana was primed to take over the Pop Art scene. Avoiding the sex and drugs associated with the movement, Indiana embraced the art-form’s ethos by stripping down ideas to their essence. The Museum of Modern Art thought this genre could translate to the limited space of a Christmas card. On a green and blue background, Indiana’s blocky red letters LOVE made their first appearance in 1965. It would not be the last. The image has been slapped on everything from t shirts, magnets, and a particularly popular series of postage stamps in the 1970’s.

Over the next few years, imitators popped up in cities around the world. Not wanting to disturb the simplicity of the design, Indiana did not put his signature anywhere on the piece. He was totally anonymous. With no recourse to sue for his art, Indiana barely turned a profit. Wrongly assuming he made a fortune, his fellow artists branded him a sell-out. Museums rejected his other work as too commercial. Excluded from the art world, he left New York. For the rest of his life, he isolated himself in the small coastal city of Vinalhaven, Maine. He hated his most famous creation. Robert Indiana wished he could have been known for more. Nevertheless, when it comes to an enormous artistic legacy, all you need is LOVE.[5]

5 A Trip to the Moon Cratered George Melies’ Career

George Melies’ talent was literally out of this world. More than any of his peers, Melies understood the possibilities of film. Trained as a magician, Melies turned his sense of showmanship into surrealistic sketches that pioneered the basics of cinematic special effects. No film better showcased his revolutionary editing and framing techniques than 1902’s A Trip to the Moon. While the shot of a space capsule jutting out of the man in the moon’s eye is endlessly referenced, the other 14 minutes are equally dreamlike. Melies’ life was less whimsical.

A blockbuster in Europe, Melies planned on recouping his special effects laden production budget by distributing the movie in the United States. Like many other inventors before him, Thomas Edison stole Melies’ success. Bootlegs and pirated copies of the movie flooded the market. Using the same business model as those Transmorpher cash grabs, Edison directed his own knockoff film called A Trip to Mars to trick the audience into seeing his version. All of the royalties were funneled to Edison. Flushed with money from ripping off Melies’, Edison used his own production company to muscle Melies’ struggling Star Films into bankruptcy.

When World War One broke out, the neglected reels of Star Films were melted down to become soles for shoes. A large portion of Melies’ movies are now lost forever. Stripped of his rightful earnings and his greatest achievements, Melies spent the last few years selling toys in a train station. Even the father of modern cinema could not get a Hollywood ending.[6]

4 Herman Melville was a Whale of a Failure

For Herman Melville, fame was as elusive as his titular white whale. The saddest part of Moby Dick’s rejection was that Melville had already known success. Both of his first two books, Typee, and Omoo, were instant hits. Churning out one adventure story per year, Melville was heralded as a great new voice in nautical yarns. In the vein of his other stories, Moby Dick was initially another rollicking tale of bold men braving the high seas. Then in 1849, he met Nathaniel Hawthorne. The Scarlet Letter author was the first person to suggest the epic quest could work as an existentialist tome. Over the next two years, Melville studied philosophy and literature. In 1851, those years of introspection resulted in the Great American Novel.

Echoing the thoughts of many future high school students, readers at the time hated the book. Noted editor, Henry F. Chorley, of the London Athenaeum, called it “as much trash belonging to the worst school of Bedlam literature.” Critically and commercially a flop, the book only sold 3,000 copies. Complaining to Hawthorne, Melville said that “dollars damn me” Hawthorne ignored Melville’s pleas, and their friendship crumbled. Melville’s income and popularity sank faster than the Pequod. His follow-up, Pierre, was similarly dismissed. Dejected, the 33-year-old Melville basically retired from writing, only releasing the occasional poem over the next decades.

In 1867, Melville plunged further into alcoholism and depression when his oldest son killed himself. In 1891, the local newspaper summed up the tragic life of the notoriously longwinded author in just six lines. His obituary could not even get his name right. Though wrongfully called “Henry”, Melville’s name lives on.[7]

3 Grant Wood Did Not Live the Simple Life

The parodies are almost as ubiquitous as the original. Through the hundreds of homages to American Gothic, the pitchfork wielding farmer and his wife have stood in for countless types of careers and relationships. Grant Wood never got to experience much of either.

Influenced by European tradition, Wood’s portfolio contains many exaggerated scenes of Iowa farmlife. Modeled after the local dentist Byron McKeeby and his sister, Nan, the couple in his most iconic work were filled with the same admiration of his town. Within weeks of its debut at the Art Institute of Chicago, the art world did not take it that way. Critics embraced the painting as a joke, a satirical take down of middle America. Wood regretted that interpretation, but went along with it as the painting’s popularity soared. Nan expressed similar discontent for the haggard stretched out face of the woman and the age gap in the relationship.

The troubled legacy extended to the world outside the painting. Internationally known as the personification of Midwestern values, Wood faced growing scrutiny about his bachelorhood. A closeted gay man, Wood claimed that he forwent marriage to take care of his sister and widowed mother. Unable to hide his sexuality, he got into a sham marriage in 1935. The marriage drained him emotionally, financially, and artistically. Wood refused to paint for years.

Outed in Time magazine, Wood was fired from teaching at the University of Iowa in 1941. His few remaining months were not much better. In 1942, Wood died from pancreatic cancer, a day before his 51st birthday.[8]

2 A.A. Milne’s Story is Sadder than Eeyore’s

Winnie the Pooh is the essence of innocence. His origin is as lovable as he is. A.A. Milne told his son, Christopher Robin, fantastical adventures of the boy and his teddy bear. The only people who could possibly dislike Winnie the Pooh just happen to be everyone involved with making it.

Winnie the Pooh was far from A.A. Milne’s first story. All totaled, Milne wrote seven novels, five nonfiction books and 34 plays. Readers abandoned him when he did not write about Hundred Acres woods. Pigeonholed as a children’s writer, Milne hated the character, because he felt he could never fully write what he wanted to again. These limitations do not come close to his son’s existential crisis.

Despite entertaining millions of children, A.A. Milne was not as similarly affectionate with his only child. Locked in his office, A.A. Milne abandoned the real Christopher Robin most days in his office to write with the one in the book. As the namesake of the character, Christopher Robin could not escape the association. While attending boarding school in 1930, the other students constantly taunted him, physically and verbally.

After school, Christopher Robin struggled to find a job, in part because of depression from “the empty fame of being his son.” Much to his parent’s protest, the inspiration for one of children’s literature most wholesome characters fixed his sadness by having sex with his first cousin, Lesley de Selincourt. The schism in the family finally ruptured when Christopher Robin publicly announced he never felt close to his parents. Not really disproving his claim, his mom and dad cut off all ties. In the last fifteen years of her life, he only spoke to his mother once. Laying on her deathbed, his mother refused to see him.[9]

1 George Ferris’ Wild Ride

What goes up must come down. If anybody would understand this, it would be George Ferris. With his eponymous invention, the Ferris Wheel, George Ferris has brought joy to thousands. The Ferris Wheel only brought him despair.

The Ferris Wheel was built out of spite. In 1891, Chicago needed an innovative display for their upcoming world’s fair. The director wanted something that could surpass the recently erected Eiffel Tower. Engineers around the country submitted proposals. Most of them amounted to constructing larger towers. The most creative was George Ferris’ unwieldy contraption of a series of carriages revolving every five minutes. Chicago dismissed the plan as structurally unsound. Ferris knew it could work. On Nov. 29, 1892, they made a deal. The World’s fair would display the prototype, but Ferris would have to fund it on his own. 29 weeks and $250,000 later, Ferris revealed his exhibition. Crowds adored it. George Ferris had reached his peak.

The downturn followed quickly. Amusement parks across the U.S. packaged their own models without compensating Ferris. For the next three years, Ferris fought against the imitators in court with little success. Falling deeper in debt, Ferris kept investing in bigger versions of his machine. Nobody was buying. With no money left, George’s wife divorced him in 1896, directly increasing his rampant alcoholism. Later that year, George Ferris died alone in Pittsburgh’s Mercy Hospital. Faced with a litany of medical issues, Ferris never sought help. He let himself succumb. He was 37. Nobody claimed his ashes for 15 months. 10 years later, his original Ferris Wheel went out too. Dismantled in bankruptcy court, the remnants were dynamited in 1906. The scraps of one of America’s greatest technical marvels were unceremoniously dumped in a landfill.[10]

For more lists just like this one check out 10 Artists Who Hated Their Own Masterpieces, and 10 Famous People Who Have Hated The Fame.