History

History  History

History  Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

10 Things You Probably Never Knew About Cannibalism

Except in times of famine, cannibalism has very rarely been about food. In most cases, from the medicine-makers of Europe to the tribes of the New World and even psychopaths such as Armin Meiwes, cannibalism has been surprisingly meaningful to those who practiced it. Most of the peoples encountered by the Colonials in the New World after 1492 did not practice cannibalism.

Spanish soldiers were instructed (initially by Queen Isabella of Spain, and later by the Pope) to actively enslave or subdue either the cannibals of the Americas or any infidels who resisted conversion. Tribal cannibalism has most certainly occurred. But the horrors of man-eating in the “civilized world” have sometimes been equally bad.

Related: 10 Facts About Human Cannibalism From Modern Science

10 The Real Cannibals Were the Europeans

It’s true. From the Middle Ages to late Victorian times, Europeans swallowed just about every part of the human body as medicine. In fact, for most people in the time of Shakespeare or Charles II, the big question was not: “Should you eat people for medicine?” so much as “What sort of person should you eat for medicine?” It started off with Egyptian mummies. Medical trade in these human remains began in the fifteenth century. Later in the seventeenth century, when supply dwindled and Egyptian authorities clamped down on the plunder, certain merchants in North Africa baked up dead lepers, beggars, or camels into a “counterfeit mummy” to satisfy continuing demand.

By this time, science preferred new flesh. One recipe of 1609 advised you to “choose the carcass of a red man, whole, clear without blemish, of the age of twenty-four years, that hath been hanged, broke upon a wheel, or thrust-through, having been for one day and night exposed to the open air, in a serene time.” This flesh should be cut into small pieces and sprinkled with powder of myrrh and aloes before being macerated in wine. It should then be “hung up to dry in the air,” after which “it will be like flesh hardened in smoke” and “without stink.”

Among those making or taking various forms of corpse medicine were Emperor Francis I, Elizabeth I’s doctor, John Banister, Charles II, chemist Robert Boyle, the doctor and pioneering neuroscientist Thomas Willis, and a host of aristocratic ladies and gentlemen. For the poor, there was fresh blood: swallowed at beheadings in Austria, Germany, Denmark, and Sweden (though one wonders if this may be propaganda or outright fantasy). You could allegedly see this going on anytime from around 1500 to 1866, and it was used especially by epileptics. In Britain, people were illicitly obtaining skulls for medicine in and even beyond the Victorian age.[1]

9 Famine Cannibalism

Until at least the eighteenth century, this was also grimly true in Europe. After the Reformation, the main reason was that the civilized people of the day were slaughtering each other on an epic scale in various wars. In 1590, with Paris besieged by Henri of Navarre, an emergency famine committee agreed that bread should be made from bones from the charnel house of the Holy Innocents Cemetery. It was available by mid-August, but those eating it apparently died.

In Germany in late 1636, in the village of Steinhaus, a woman allegedly lured a girl of twelve and a boy of five into her house, killed them both, and devoured them with her neighbor. In Heidelberg around this time, men were said to “have digged out of the graves dead bodies, and…eaten them,” while one woman “was found dead, having a man’s head roasted by her, and the rib of a man in her mouth.” Piero Camporesi tells of how, in Picardy during this conflict, the Jesuit G.S. Menochio saw several inhabitants so crazed with hunger that they “ate their own arms and hands and died in despair.” [2]

8 The French Traveler Who Probably Preferred to Live with Cannibals

In the 1550s, the French traveler Jean de Léry spent some time living with the Tupinamba cannibals of Brazil. All too often, once he was home in France, Léry must have wished he was safely back in Brazil with the ferocious cannibals. Beginning on August 24, 1572, in Paris, the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre ultimately claimed the lives of perhaps 5,000 Protestants—slaughtered by Catholics. And shortly after that (writes Frank Lestringant, an academic who admittedly combines allegory with facts), Léry saw a French Protestant executed by Catholics in Auxerre. The victim was not only ritually executed, but also had his heart “plucked out, chopped in pieces, auctioned off, cooked on a grill and finally eaten with much enjoyment.” Though given the extent to which people will lie to defend their position, it is probable that he made up the latter part of that tale.

Nor was this all. In 1573, Léry found himself in war-torn Sancerre, which endured an appalling siege and severe levels of famine. Lestringant tells of how, in one starving family, a small girl died. Soon after, the elderly grandmother persuaded the child’s parents to eat her. The grandmother was later condemned and executed. Having seen a good deal of cannibalism in Brazil, Léry found himself confronted with the dead girl’s butchered carcass. At this point, his whole body made its own judgment, and he spontaneously vomited at the sight.[3]

7 Warring Christians Were Known to Eat or Drink Each Other

When the Spanish sacked the Dutch city of Naarden in Holland in December 1572, around a hundred citizens seeking to escape into the snowbound fields were overtaken by Spanish soldiers, stripped naked, and hung on trees to freeze to death. And it was here that the invading armies, “becoming more and more insane as the foul work went on,” were said to have “opened the veins of some of their victims, and drank their blood as if it were wine.”

In his unusually enlightened essay “On Cannibals,” the remarkable French thinker Michel de Montaigne insisted that eating a living person was more barbaric than one who was dead. He added that humans at that time had both read about and seen people roasted by degrees and “bit and worried by dogs and swine.” This was done while the victim was aware and alert—and indeed performed “not amongst inveterate and mortal enemies, but neighbours, and fellow citizens, and which is worse, under colour of piety and religion.”

In April 1655, the Protestants of the Piedmontese valleys were massacred by Catholic troops. A high-ranking French soldier, Monsieur du Petit Bourg, later told of soldiers eating boiled human brains, tricking their comrades into consuming “tripe” (in fact, the breasts and genitals of one of the Protestant victims), and roasting a young girl alive on a pike. The soldiers who killed Daniel Cardon of Roccappiata readily ate his brains after frying them in a pan. And having taken out his heart, they would have fried this also, had they not been “frighted by some of the poor peoples’ troops…coming that way.”[4]

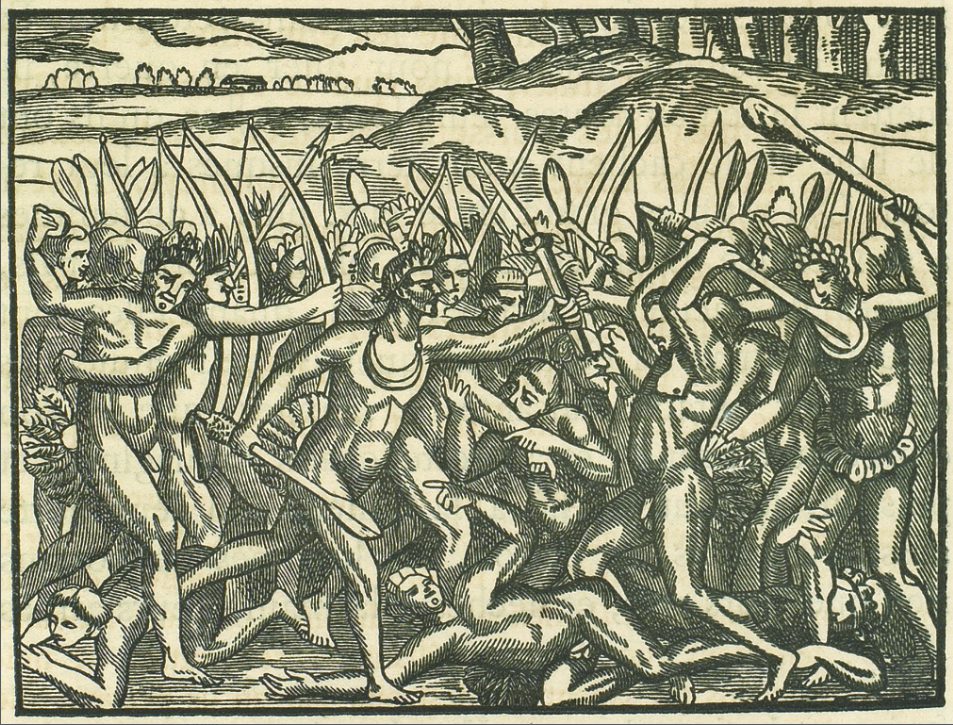

6 Much Supposedly “Savage Cannibalism” of the Americas Was Entirely Consensual

The best-known Christian accounts of “savage cannibalism—often with lurid images—tended to focus on violent man-eating: exo-cannibalism. But a great deal of tribal cannibalism was purely internal and consensual. For example, in funerary cannibalism (or endo-cannibalism), a tribe ate its dead as a form of mourning. Such rites were highly sober, complex, and essentially religious.

This is vividly clear in accounts of Brazilian Wari’ cannibalism given by anthropologist Beth Conklin. Wari’ funeral cannibalism took place relatively recently—perhaps as late as the 1960s—until stamped out by invasive Christian missionaries. The eating of the dead was part of a somber and elaborate ceremony: the corpse was painted with red annatto, and the firewood for cooking was decorated with the feathers of vultures and macaws. The mourners sang and burned the house of the deceased.

There was no question of simple appetite here. In fact, in the case of a dead tribal elder, the long mourning period meant flesh was probably putrid by the time it was consumed. Mourners might have to force down this rank flesh and even vomit but did so out of respect for the spirit of the deceased. Interestingly, the Wari’ were horrified by the notion of Christian burial, the imprisoning of a corpse in cold, dank earth—something which they considered to be polluting.[5]

5 Like the Mafia or Academics, Savage Cannibals Only Killed Their Own

As for exo-cannibalism? Aggressive man-eating was practiced against rival tribes as part of a radical aggravation of violence and hatred. Thanks to another dauntless French traveler, André Thevet, we know how complex and religious this kind of cannibalism was. The Tupinamba would assemble the entire tribe to eat such a captive. After he was clubbed to death and roasted, every tribe member would eat something, leaving only a cleanly picked skeleton some hours after his death. But by this time, the captive victim had actually lived with his enemy hosts for a year. He had his own house and a new wife from the tribe and had even fathered a child. This child, too, would be eaten along with the father. The key to this strange puzzle is “incorporation.” In every possible way, the enemy captive was absorbed into the victors’ tribe: first socially and symbolically, and then quite literally.

Similarly, Peggy Reeves Sanday has emphasized the complex social and religious character of Tupinamba rituals. The aggressive participants might at one stage be “howling at the tops of their voices…their eyes flashing with rage and fury,” while at another, the watching Jesuits were struck by the fact that the torturers’ faces clearly expressed “gentleness and humanity” toward their tormented captive. Equally, the ceremony was very carefully controlled and prolonged, with the victim being intermittently revived so that he should not die before the appointed time.

Despite suffering pain and exhaustion seemingly beyond the limits of human endurance, their victim would essentially cooperate in the whole proceeding because he shared certain basic religious beliefs with his tormentors. He must, for example, show extraordinary courage, knowing as he did that, after the tortures at daybreak, he was being watched by the sun god.[6]

4 Chinese Cannibalism (I): How much do you love your mother-in-law?

Surprisingly, until recently, China also had some startling examples of both consensual and violent cannibalism. Daniel Korn, Mark Radice, and Charlie Hawes explain how, for centuries, the traditions of filial piety known as ko ku and ko kan involved the daughter-in-law treating her sick, elderly in-law through cannibalism. If you ever have to do one of these yourself, choose ko ku. The “donor” takes a very sharp knife, slices off part of their upper arm or thigh, and mixes it into soup, which produces a miraculous recovery in the recipient.

Ko kan is a bit more serious. The donor cuts open their own midriff and (not without some effort) locates their liver. They then carve out a piece and feed it the same way to the ailing in-law. The authors noted that the liver has astonishing powers of regeneration so that donors may, in fact, have been able to survive this ritual. The recipient of these gourmet specialties was never supposed to know that they were not ordinary food.[7]

3 Chinese Cannibalism (II): How much do you hate your class enemies?

And exo-cannibalism? Hawes reveals how, in the later 1960s, in the throes of China’s violent Cultural Revolution, hatred of new class enemies reached visceral intensity in a very short space of time. How bad was it? At a school in Wuxuan Province, students turned against their teachers. The Head of the Chinese Department, Wu Shufang, was condemned as a class enemy and beaten to death. Another teacher was forced to cut out Shufang’s liver, which was cooked in strips over a fire in the schoolyard. Before long, the cannibalism had spread until “the schoolyard was full of the smell of students cooking their teachers.”

In another incident, a young man was attacked and tortured because he was the son of an ex-landlord. While still barely alive, he was bound to a telegraph pole and taken down to the river. The attackers cut open his stomach and removed his liver; the cavity was still so hot that they had to pour river water in to cool it. Once again, the liver of the landlord’s son made a “revolutionary feast for the villagers involved.” In all, some 10,000 people are thought to have taken part in cannibalism in these episodes, with up to 100 victims being eaten. These fiercely guarded internal secrets were revealed by Zheng Yi, a former Red Guard member, now in permanent exile as a result.[8]

2 And the Prize for the Nastiest Cannibals in the World Goes to…

Here are two strong contenders. The seventeenth-century French author, César Rochefort, claimed that “the inhabitants of the Country of Antis” in South America were crueler than tigers. When eating “a person of quality”:

These unmerciful people, having stripped him, fasten him stark naked to a post and cut and slash him all over the body… In this cruel execution they do not presently dismember him, but they only take the flesh from the parts which have most, as the calf of the leg, the thighs, the buttocks, and the arms; that done, they all pell-mell, men, women, and children, dye themselves with the blood of that wretched person; and not staying for the roasting or boiling of the flesh they had taken away, they devour it like so many cormorants, or rather swallow it down without any chewing… Thus the wretch sees himself eaten alive, and buried in the bellies of his enemies…

Once again, however, even this had a certain degree of honor involved—it was a person of quality who got the very worst treatment, and he was accorded respect by the Antis if he kept silent during his ordeal.

With this in mind, the top prize may go to the cannibals of the Solomon Islands. Earle Labor vividly describes the time Jack London and his wife Charmian spent there in the summer of 1908. A little more than a century ago, some Solomon Islanders still seemed to have been eating people and to have regarded them without any ritual or religious interest, but merely as tasty food. One recipe for “long pig”‘ (writes Labor) called for “breaking the bones and crushing the joints of victims…then staking them, still living, up to their necks in running water, often for days, until they were considered sufficiently tenderized for cooking.”[9]

1 Cannibal Myths

As we have seen, potentially one of the biggest distortions in history across the past 500 years was the description of “savage cannibals” by those who were practicing it on an industrial scale back in Europe. The tendency to debase tribal peoples in this way prompted the historian William Arens to try and deny that cannibalism had ever been practiced by any tribe—a perhaps well-meaning attempt that has now generally been discredited.

What is also interesting is how cannibalism acted as a kind of imaginative whirlpool, sucking in other lurid transgressions or phenomena. So in 1688, we hear of the Chirihuana, a Peruvian people who not only devoured their enemies but allegedly “went naked, and promiscuously used coition without regard either to sisters, daughters or mothers.” For their part, however, the Chirihuana were equally contemptuous of the Spanish viceroy, Francisco de Toledo. Forced to flee the region and carried in a litter by Spaniards and Indians, Toledo departed with the Chirihuana shouting “curses and reproaches, saying, ‘throw down that old woman from her basket, that we may eat her alive.’”

Even darker still was the tale (recounted by Francis Bacon, among others) that at the siege of Naples by the French in 1494, certain “wicked merchants barrelled up man’s flesh (of some that had been lately slain in Barbary) and sold it for tuna.”[10]