Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Technology

Technology 10 Hilariously Over-Engineered Solutions to Simple Problems

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Ironic News Stories Straight out of an Alanis Morissette Song

Politics

Politics 10 Lesser-Known Far-Right Groups of the 21st Century

History

History Ten Revealing Facts about Daily Domestic Life in the Old West

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Products Surprisingly Made by Inmates

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Dragged out of Retirement for One Key Role

Creepy

Creepy 10 Lesser-Known Shapeshifter Legends from Around the World

Animals

Animals 10 Amazing Animal Tales from the Ancient World

Gaming

Gaming 10 Game Characters Everyone Hated Playing

Crime

Crime 10 Terrifying Serial Killers from Centuries Ago

Technology

Technology 10 Hilariously Over-Engineered Solutions to Simple Problems

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Ironic News Stories Straight out of an Alanis Morissette Song

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Politics

Politics 10 Lesser-Known Far-Right Groups of the 21st Century

History

History Ten Revealing Facts about Daily Domestic Life in the Old West

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Products Surprisingly Made by Inmates

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Dragged out of Retirement for One Key Role

Creepy

Creepy 10 Lesser-Known Shapeshifter Legends from Around the World

Animals

Animals 10 Amazing Animal Tales from the Ancient World

Gaming

Gaming 10 Game Characters Everyone Hated Playing

10 Things You Thought You Knew About The Romans (But Don’t)

The Romans are often portrayed as a civilization given over to debauchery and decadence, a once-great empire gorging itself on food, alcohol, and sex while watching people fight to the death in the gladiator arena.

In fact, Roman society was based on a strict rule of law, which, although not democratic, took account of the rights of ordinary Roman citizens. Citizens were expected to live their lives according to a moral code, mos maiorum, which set out the virtues expected of them—including integrity, frugality, sincerity, perseverance, and public service.[1]

So who can we blame for this misconception? Kirk Douglas? Hollywood just loves a man in a toga, and historical accuracy is optional, right? Here are ten things you thought you knew about the Romans that are just plain wrong.

10 They Didn’t Build Vomitoriums So They Could Eat A Lot

According to popular myth, vomitoriums were purpose-built rooms added to the side of feasting halls where guests could go to vomit when their stomachs became too full, thus making some room and enabling them to return to the table and carry on eating, which, when you think about it, it ludicrous. Who would want a special room for throwing up?

The Romans did have vomitoriums. Lots of them.[2] And they were often attached to the side of feasting halls. So what were they? They are anterooms, a room into which crowds leaving the main hall may “spew forth.” In other words, vomitoriums were lobbies, exits, and passageways.

The Colosseum in Rome had 80 vomitoria. That should have been a clue. For future reference, just because a word in one language sounds a little bit like another word in a different language, we should not jump to conclusions. And although the Romans certainly did have elaborate banquets, there is no evidence that they habitually made themselves sick during them. And if they did, they probably used the bathroom.

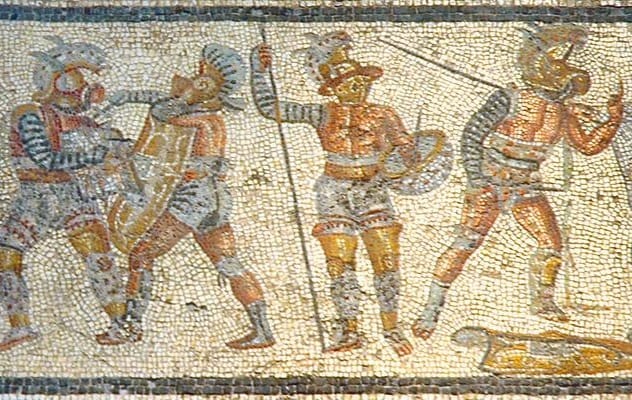

9 Thumbs Up/Down Was Not A Thing

There is a widely held belief that when gladiators fought in the arena, the emperor, or sometimes the crowd, would decide the fate of the defeated man. Thumbs up, he lives. Thumbs down, he dies. Who is responsible for this misconception? Kirk Douglas? Or was it Joaquin Phoenix in that other film about a gladiator?

In Rome, the thumbs down signified “swords down,” or “stop fighting,” which meant that the losing gladiator would live to fight another day. In fact, fighting to the death rarely occurred. The gladiators were highly skilled and had undergone intensive training. Killing them regularly would have meant that a lot of time and money had been wasted.

Most commonly, the gladiator fight was one of endurance. Wielding those swords is tiring, after all. As long as one gladiator was the clear victor, either because the other was wounded or exhausted, the fight was decided. Very occasionally, sponsors would pay extra for a death match and would have to pay compensation to the trainer on the losing side for lost income.

Despite the evident risks, gladiators were celebrities. Slaves could win their freedom, and those who made it to the end of their career in one piece could earn a good living as a trainer. In 2007, archaeologists found the remains of a gladiator graveyard. Some skeletons showed wounds that had healed, showing that they had been treated afterward, though others suffered lethal blows from swords and tridents. Those skeletons with hammer blows to the head are thought not to have received their injuries in the ring but to have been badly wounded and thus put out of their misery later.[3]

That was nice of them.

8 They Didn’t Speak Only Latin

Wait, what? It is commonly assumed that everyone in ancient Rome spoke Latin, but that is not true. Latin was the official written language of Rome, but many languages were spoken, both in Rome itself and across its wide empire. Some of the more common languages spoken in Rome were Greek, Oscan, and Etruscan.[4]

Latin was the uniform language across the empire, but there were many local variations. In the early 14th century, Dante Alighieri identified over 1,000 variations of Latin spoken in Italy alone. It was only in written documents that any uniformity existed. Even the Roman patricians probably weren’t speaking Latin all the time, and Greek was considered the language of the educated elite.

Because of the vast distance that the Roman Empire covered, a single language was essential for the orderly business of government, so Latin was used throughout the Roman world for official business, but it is not true that all Roman citizens habitually spoke Latin.

7 Plebs Were Not Poor And Ignorant

Today, the word “pleb” is considered an insult, and to be plebeian is to be low-class. In 2014, a British MP was alleged to have called a policeman a pleb, causing a scandal that forced him to resign his ministerial post.

In Rome, however, to be a plebeian simply meant to be an ordinary citizen, as opposed to the patrician ruling class. Although originally excluded from public office, plebeians fought hard for their rights and, on more than one occasion, even withdrew from the state and formed their own governance until such time as their rights were respected.

The patricians were descendants of the original ruling families and thus formed a Roman aristocracy. Like the upper classes everywhere, they were to discover that class does not always equate to money, and being on top today does not mean you will stay that way forever.[5] The plebeians gradually asserted their rights until they had equal status with the patricians, and the old order crumbled away.

6 They Didn’t Wear Togas All The Time

Whenever there is a Hollywood movie about Rome, they immediately break out the togas, making the costume department’s job easy. In actual fact, there was a wide variety of styles of toga across the empire and through the ages.

A toga is, simply, a long piece of cloth which is worn draped over the shoulder. It was only to be worn by men, and usually then only on grand occasions. Early togas were simple in design, while later versions were elaborate, heavy, and often cumbersome garments. A hierarchy of togas existed, almost like a uniform, so that citizens could tell the social rank of the wearer. The emperor’s toga, of course, was purple.

For everyday wear, however, the Romans favored something a little more practical. They often wore a tunic made from linen or wool.[6] Soldiers wore leather coats, and some even favored bearskins or the pelts of big cats. Short tunics, however, indicated a low-born person or a slave.

Women, slaves, and those who had been exiled from Rome were all forbidden to wear a toga. Toward the end of Roman rule, citizens even began to wear trousers, which had been previously reserved only for barbarians.

5 They Didn’t Salt Carthage

Rome and Carthage (now part of Tunisia), fought three wars over the course of roughly a century. Carthage was finally destroyed in 146 BC, with 50,000 prisoners of war sold into slavery by the Roman victors.

The Third Punic War was certainly bitter and bloody. And when Rome won, the city of Carthage was razed to the ground, “leaving not one stone on top of another.” However, the story that the Roman army salted the earth, rendering the ground infertile for generations, appears to be a myth. The story of the salting symbolized the total destruction of the enemy and was well-known to later scholars, but there is no evidence in contemporaneous accounts that the land was actually salted.

In any case, salt was a valuable mineral. Vast quantities would have been required to do anything more than fleeting damage to soil, and it is unlikely that, having sold its citizens into slavery and razed its buildings to the ground, the Romans would have spent money, time, and effort digging salt into Carthage’s soil.[7]

4 Nero Did Not Fiddle While Rome Burned

When it comes to biographers, it pays to get someone who likes you. According to Nero’s biographer, Suetonius, Nero “practised every sort of obscenity,” from incest to murder, with cruelty to animals thrown in.

Suetonius goes on to describe how, when fire swept across Rome in AD 64, Nero climbed to the top of the city walls dressed in theatrical clothes and wept while reciting lines from an epic poem about the destruction of Troy. A later historian, Cassius Dio, elaborated on the story, and the theatrical clothes became “cithara player’s garb.” The cithara was an early precursor of the lute, itself a forerunner to guitars.

So, it might be thought possible that the emperor was so unconcerned for the citizens of Rome that he practiced the fiddle while watching the flames engulf them. When Shakespeare wrote Henry VI, Nero was still playing a lute while “beholding the towns burn.” However, the lute had become a fiddle in 1649, when playwright George Daniel wrote, “Let Nero fiddle out Rome’s obsequies.”[8]

And that was it.

Nero’s biographer took advantage of the prevailing mood when he wrote his description of the emperor’s bizarre behavior, as Nero was not a popular ruler. There was even as suspicion that the fire was rather auspicious, since Nero had been wanting to build himself a new palace and needed to make some space. This may have been the case, but there seems to be some evidence that Nero was not actually in Rome at the time of the fire, and the whole episode was made up.

3 The Romans Didn’t Invent The Nazi Salute

There is a common belief that the Nazi salute is derived from that of the Roman Empire—arm extended slightly upward with palm facing down. However, there is very little evidence for this. There are no documents from the period describing the form the salute took, though it is all but certain there was one.

The myth of the Roman salute may have begun with the painting Oath of the Horatii (shown above) in 1784, which shows a group of soldiers in the same pose, but there is nothing to suggest that this is anything other than the painter’s artistic license at work. Early films (yes, Hollywood again) reinforced the idea. Mussolini’s fascist party, no doubt with the idea of harking back to a glorious Italian past, copied what he believed to be the salute of his forefathers.[9]

And Hitler, well, pinched the idea from him. He also pinched the swastika from the Buddhists (one of many religions to use the symbol), but that is a different list.

2 Caligula Never Made His Horse A Consul

The name Caligula conjures up all sorts of images, not all of them pleasant. So many myths surround his life that it is difficult to know which of them are really true. Contemporaneous accounts of his rule come to us mainly from the writer Seneca, who may have been biased due to the fact that the emperor almost had him put to death in AD 39 for associating with conspirators.

We do know that Caligula was made emperor at the age of only 25. He began well enough, declaring an amnesty for anyone imprisoned under the previous emperor, abolishing taxes, and organizing some Roman games. However, he fell ill a few months later, possibly as a result of taking too many baths or perhaps because of the large amounts of sex he was having. Whatever the cause, he contracted a “brain fever,” from which he never fully recovered.[10]

He began to show signs of paranoia. He had some of his closest advisors killed. He banished his wife and forced his father-in-law to commit suicide. Rumors spread that Caligula had slept with his own sister, but there is little proof of that, except that they were said to be close. Caligula had himself declared a living god and took to sitting around in his temple waiting to be presented with offerings. He spent less time on the governance of Rome and more on entertainment of all kinds. He once had hundreds of ships tied together to make a bridge so that he could ride over the Bay of Naples on his horse.

Caligula was certainly fond of his horse, which is possibly the source of the rumor that Caligula had made the animal a consul and was taking its advice. However, there is no contemporary evidence that he ever promoted his steed to government. A writing by Suetonius states that Caligula proclaimed his intention to do so, not that he actually did. Knowing Caligula, it’s anyone’s guess as to whether he looked to the horse for advice, though.

Caligula died in AD 41 after having, somewhat foolishly, announced that he planned to move to Alexandria in Egypt, where he believed he would be worshiped as a living god. He was stabbed to death by three of his guards.

1 Gladiators Were Not All Slaves

The myth of the gladiator as handsome slave, with or without a dimple on his chin, is only partially true. Some gladiators were slaves; others were convicted criminals. But some were men who volunteered for the arena, attracted by the fame and the money that it brought.[11] Most were common working men, but some were patricians who had lost their fortunes. And some gladiators were women.

The first recorded gladiatorial games were held in 264 BC. In 174 BC, 74 men were recorded fighting in games lasting three days. In 73 BC, a slave by the name of (guess who) Spartacus led a revolt among gladiators, but still the games grew in popularity. Caligula put his own twist on the games by having criminals thrown to wild animals in the center of the arena.

By AD 112, the sport was so popular that when Emperor Trajan hosted Roman games to celebrate his victory in Dacia, 10,000 gladiators—men, women, rich, poor, slave, and free—all fought in games which lasted months.

Ward Hazell is a writer who travels, and an occasional travel writer.

Read more facts you may not have known about the Roman Empire on 10 Facts About Ancient Rome That Are Rarely Covered In School and Top 10 Recent Surprising Glimpses Into The Ancient Roman World.