History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Wildly Unsuitable Olympic Venues for Competitors

Today, we think of Olympic events as being held in state-of-the-art venues built specifically by the host city for that year’s illustrious games. When cities are awarded the opportunity to host, the planning committee gets right to work. The result has given us spectacular Olympic venues where the athletes compete, hoping to win gold.

However, this has not always been the case. Since the Summer Games restarted in 1896, Olympians have sometimes had to take part in conditions that have ranged from inconvenient to downright dangerous. Here are ten instances when Olympic venues were wildly unsuitable!

Related: 10 Amusingly Bizarre Tales From The First Modern Olympics

10 London, 1908

When the British and Australian teams walked out onto the White City Stadium pitch to play the Olympic rugby final, they were confronted with a playing area that posed a potentially bigger problem than the damp grass. Running immediately alongside the pitch was the open-air Olympic swimming pool. Players could cope with the basic conditions, but a possible drop of several feet was more hazardous.

Netting was stretched precariously over the gap to try and catch any erstwhile kicks made toward the pool, and large mattresses were spread along the closest edges of the pool to try and prevent any injuries.

The ball would regularly be kicked out of play into the pool, and it was reported that the Australians were better at handling the slippery ball—ending up 32-to-3 winners. The ball might have taken a battering, but the players at least avoided any pool-related injuries.[1]

9 Tokyo, 1964

Water polo competitors arriving at Tokyo’s Olympic pool found that the water was too shallow. This prompted immediate complaints from some teams about taller players being able to stand on the bottom of the pool, giving them an unfair advantage. The Hungarian coach claimed somewhat exaggeratedly that even his shortest player could stand on the bottom.

Keeping quiet was the Yugoslavian team—the tallest group in the tournament. Their players could easily shoot from a standing position.

The event took place with attempts by the hosts to raise the water levels. Perhaps justice was done in the end—the Yugoslavians only earning silver behind the victorious Hungarians.[2]

8 Athens, 1896 and Antwerp, 1920

Swimmers have often been the hardiest of all Olympic competitors, with conditions ranging from wild at worst to basic at best.

With no Olympic pool, entrants in the first modern Olympic Games had to endure the freezing waters of the Bay of Zea—racing in temperatures that reached up to only 13°C (55°F)—in chilly weather. With all the races taking place over one day, few shelters had been provided, meaning that the swimmers had little chance of warmth. After winning two events, the Hungarian swimmer Alfred Hajos said that the cold was such that “his will to live completely overcame his desire to win.”

The newly built Antwerp pool for the 1920 Summer Games was commended by the IOC president—others disagreed. American swimmer Aileen Riggin remembered that it was disliked intensely by her teammates. She likened it to “a ditch that had just been dug, with an embankment on the side for protection in case of war.” Swimmers reported that the water was black and freezing, with competitors having to wear several layers of clothing just to keep warm after racing.[3]

7 Paris, 1900

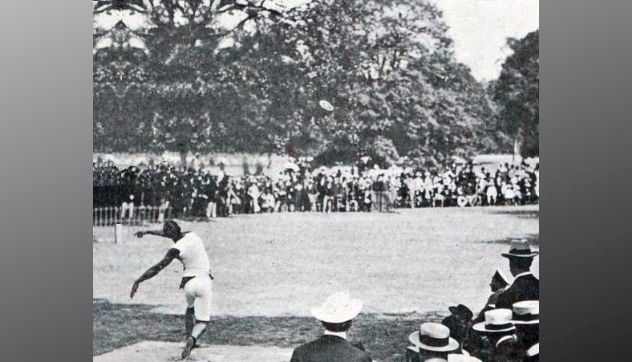

Regarded as one of the worst modern Olympics, the Paris Games were added to the city’s Universal Exposition World Fair almost as an afterthought. The organization, taken out of the IOC’s hands, was shambolic and some venues totally inadequate.

Track and field events took place in areas described as being more suitable for walking and picnics—the general public often wandering through the various competitions being held. The athletics track was an uneven and frequently wet field, with long grass in parts and not always marked properly. Runners in the hurdle races found that they were jumping over broken telegraph poles, while the 400m hurdlers also had to contend with a water jump in the final straight—fortunately, not a lasting novelty.

The discus and hammer throwing events took place in a narrow tree-lined lane. The many attempts which hit the trees were designated as “no throws.” With minimal safety regulations, spectators had to keep a careful watch out for misdirected flying implements.[4]

6 St. Louis, 1904

Like Paris four years earlier, these Summer Games were poorly organized and mismanaged. Similarly, they were added to the city’s World Fair event.

For the swimmers and water polo competitors, facilities were particularly dreadful—with tragic longer-term consequences. An artificial lake, created in the middle of the World Fair to hold life-saving demonstrations, was also used for some of the agricultural exhibits. Cattle grazing nearby would wander into the water, contaminating it. This evidently did not appear to concern the organizers.

It was in this dirty pool that the swimming and water polo events took place. Only three teams, all American, entered the latter event—eventually won by the New York Athletic Club. Although held at the far end of the lake, the foolishness of playing in such filthy water would later prove devastating. Within a year, four of the water polo players died of typhus.[5]

5 Berlin, 1936

Until the 1948 Games, basketball tournaments were held outside. No problem if the weather was fine—but then came Berlin.

Matches in the 1936 Olympics were played on sandy tennis courts. On the day of the final, it rained…and rained, turning the court into a quagmire and making scoring ridiculously hard. When the ball hit the water-soaked ground, it wouldn’t move. Plus, the lumpy ball made passing difficult.

The finalists, USA and Canada, both wanted the match postponed, but the German organizers insisted that the match go ahead as scheduled. In an interview many years later, one of the Canadian players said that “Michael Jordan could have slipped from foul line to foul line and scored a basket without taking any steps.” At the end of the inevitably low-scoring final, the USA had triumphed by 19 points to 8. Canadian player, Jim Stewart, had the ball in his possession at the final whistle and managed to smuggle it off of the court—to keep as a souvenir, with the help of his watching wife. His teammates didn’t object. It was like a soggy, muddy football (soccer ball for you Americans). Nobody else wanted it.[6]

4 London, 1948

Known as the “Austerity Games,” war-torn London hosted the first Olympics in twelve years.

The running track was only laid at Wembley’s Empire Stadium two weeks before the start of the Games. What the organizers hadn’t planned for was the athletics program running late into the day. A real problem since the stadium had no infield lighting.

On a soggy Friday evening, the second and final day of the decathlon was due to finish at 6 pm—delays meant that darkness had descended with three events still to go. The eventual winner, 17-year-old Bob Mathias from the USA, had already spent time with discus officials searching on hands and knees for a dislodged flag marker hole. Just after 9 pm, he started the pole vault on his own as his rivals had already finished. Assisted by a teammate who pointed a flashlight up into the night sky at the bar, Mathias recorded the winning height.

A solo win in the javelin followed, although the no-throw foul line was not visible in the gloom. At 10.30 pm, the 1500 meters was run in driving rain, with some car lights helping to illuminate the track. Although coming in third in the race, Mathias had eventually beaten the dark and all other obstacles to become an Olympic champion—the youngest to ever win decathlon gold.[7]

3 St. Louis, 1904

Back to St. Louis, it wasn’t only the competitors in the water who faced problems. Similarly, poor organization turned the Games’ toughest event into a near farce—only luck prevented a more serious situation from occurring.

The marathon course was an unreasonable endurance test, particularly for the many inexperienced competitors. Starting in heat approaching 35°C (95°F), the unpaved roads were thick with dust. The runners had to climb seven steep hills and negotiate rough, stony ground while also dodging pedestrians and other obstacles.

Several athletes collapsed after inhaling too much dust, including one who nearly died from the effects. To make matters worse, only two water stops were available.

The shambles continued to the end. American Fred Lorz was declared the winner but was found to have had a lift in a car mid-way through the race for ten miles. His totally exhausted teammate, Tom Hicks, was then awarded the win—only finishing with some help and being given a “medicinal” concoction of brandy, eggs, and strychnine along the route. A potentially fatal tonic had it not been for help from doctors immediately after the race. [8]

2 Beijing, 2008

Even more recent games are not exempt from poor planning. Beijing’s Games posed a potentially serious problem for all competitors—the most polluted Olympics in history. The IOC was sufficiently worried in the year leading up to the start to think about postponing some endurance events.

As the Olympics began, evening showers and changes in wind direction helped to ease the pollution, although the sun could barely be seen through the smog at times. Competitors often struggled in the heat and humidity, with added rest breaks being taken. The football finals saw stoppages after 30 minutes in each half. Athletes suffering from asthma were particularly affected. Some medal contenders decided not to risk their health, including marathon world-record-holder Haile Gebrselassie, who pulled out earlier in the year. and 2004 cycling silver medallist Sergio Paulinho due to respiratory difficulties.[9]

1 POW “Olympics,” 1944

Taking a slight liberty here, but if anything demonstrates how the “Olympic spirit” could overcome appalling conditions, then the POW “Olympic Games” must be the best example.

War had caused the cancellation of the 1940 Tokyo and 1944 London Games, but Polish prisoners of war in German-controlled camps were determined to have their own Olympics. A similar event earlier in 1940 had to be held in secret—the discovery of the activities would have resulted in severe punishments for the POWs from Stalag XIII A in Nuremberg.

In 1944, however, the guards gave permission for an “Olympics” to be held in the harsh environment of Woldenberg Camp—with certain limitations. Nevertheless, the Polish POWs enthusiastically made up an Olympic flag from old bedsheets along with paper medals and special stamps.

The many events included track and field events, basketball, football, handball, and volleyball. The boxing tournament was popular but was cut short due to injuries caused by the weakened physical state of the prisoners. Unsurprisingly, the camp authorities would not allow pole vaulting, fencing, javelin, or archery events to take place. In all, 369 prisoners participated in 464 competitions, including some deemed social and cultural as was common in the Games at that time.[10]