Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Top 10 Horrifying Artworks That Will Give You Nightmares

The visual arts have gotten a bad rap of late. A tradition starting with Duchamp’s graffitied urinal has led to a procession of “What is art?” pieces that litter galleries all over the world. This “art” is fawned over by people who, were they alive in the mid-19th century, would have invested more in monocles and beaver fur stoles than time learning about the natural world, art, and literature. Once upon a time, this was not the case—art was inspired, and it inspired. In some unexamined corners of today’s cultural landscape, this trend remains. Waiting.

But art was not always the joyous, primary-color explosions of a Van Gogh or the blissfully serene pastel hues of a Monet. Nor was it always the heroic subjects of Greek and Roman marble sculptors or the study of beauty painted by Klimt, Botticelli, or Michelangelo. The darker side of existence has a place too…

“The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance” – Aristotle; read this list with that quote in mind, and you’ll never sleep again.

Related: 10 Shocking Pieces Of Erotic Art From The Ancient World

10 Mad Kate

Heinrich Füssli (1806, Oil)

The unexpected, the uncanny, or, to be more academic, an image that displays “situational ugliness” is foundational in engendering a fear response in people. Famed author and medievalist Umberto Eco wrote of this phenomenon in his book On Ugliness: “The governing principle behind every story about ghosts or other supernatural events, in which we are frightened or horrified by something that isn’t going the way it should…”

Look at her. Things certainly aren’t going the way they should here.

If you look from the bottom of the portrait upward, slowly, one could be forgiven for expecting a rather nice, gentle-looking lady, perhaps waiting for loved ones to join her for a picnic. Look at the periphery—a blue sky, a bit of brush/hedgerow, a sweeping mountainside, and sun rays glinting. Now her face. The wild stare, pupils pointing in directions we don’t expect, wild hair, and a wilder cape flowing upward to a (suddenly, jarringly) jet-black sky. Plus, the title—Mad Kate. She certainly looks it.

This painting exemplifies two core fears we all have—a loss of sanity (autonomy of mind) and coming face-to-face with the unexpected. Who amongst us can claim that they would like to be alone in the wilderness with Mad Kate?[1]

9 Drawings by Abused Children

(Tragically) Ongoing, Mixed Media

The innocence of children is a miracle. When such innocence is exploited, roughly dragged from the child by the predations of an adult, we can all agree that it is among the most heinous of crimes mankind can commit. Objectively evil.

Many children express elements of their trauma via art—the stereotype of kids drawing silly little pictures of stickmen and women standing outside a boxy-looking house with a smiling sun in the top corner is given a tragic bent when the child in question has suffered abuse. Houses are drawn without doors and windows, showing there’s no escape. Pictures of a parent may show them smiling, but their mouth tends to be full of huge, sharp teeth. Sometimes, instead of normal arms, an abusive adult gets depicted with elongated grasping arms or fingers. The child often draws themselves without arms.

When a child is suspected of having been abused, sometimes it is only prominently evident in their drawings. This is, in a way, a good thing—these subtle indicators can lead to authorities or unwitting parents to uncover the perpetrators and have them brought to justice. In another way, it is utterly tragic—a blank piece of paper and a box of crayons should be a chance for kids to express their imagination, bringing their colorful alternate worlds to ours. When their minds are full of unspeakable horrors, it isn’t surprising that’s all they can draw. These “works of art”‘ are the hardest to view but perhaps the most necessary in avoiding further evil.[2]

8 Untitled

Zdzislaw Beksinski (1975, Oil)

Commentators have referred to Polish artist Zdzislaw Bekinski as “The Nightmare Artist.” Can’t argue with that! The work that has been selected here—Untitled (the same “title” that most of his work bares), is one of the hundreds of twisted, spine-gnawing works that plumb the depths of our collective psyche. It’s simply horrific.

Otherworldly, eldritch horrors stalk around madness-inducing landscapes, causing the viewer to thank the Lord that these creations are just paint dragged across the canvas. Having said that, who would hang this on their wall without expecting that one night, if the planets are aligned just right (or, for the owner, wrong), these creatures, twisted agonized humans, and demonic wraiths may begin to slip into our reality?[3]

Sweet dreams are not made of this.

7 Gas

Edward Hopper (1940, Oil)

Artist Charles Burchfield once commented that American painter Edward Hopper’s work was an “honest presentation of the American scene…Hopper does not insist upon what the beholder shall feel.” Well, Charlie boy, we cannot say what exactly Hopper meant for the viewer when he painted Gas, but once you consider the statement:

“This is Purgatory!”

Then it’s hard not to see that in the work. So too with the sentences “A murder is about to occur” or “A natural disaster is moments away.” The overwhelming sense of foreboding in this particular piece is impressive, given that Hopper often relied on a darker palette and hefty use of shadow, bland/dank interior settings, or night-time city scenes. Not in Gas—here, we’re outside. It’s bright daytime. It’s just a gas station. But, as though Hopper had infused the oil paints themselves with creeping dread, there’s something very wrong with this scene. Or it’s just an old gas station. Well, every slasher flick has one…[4]

6This Is Worse

Francisco Goya (1815, Drypoint)

There are many visual artists who have attempted to capture the essence of unfettered warfare throughout the centuries—Otto Dix’s stylized depictions of wounded soldiers after WWI, J.M.W. Turner’s Battle of Trafalgar captures naval warfare during the Napoleonic era, and, of course, Pablo Picasso’s cubist nightmare Guernica, heralding a new age of war in the skies. But Francisco Goya’s seminal series of drypoint drawings, The Disasters of War, are perhaps the most visceral, the most shocking snapshots of what a war on the home front, coupled with corruption and an immiserated populace, can look like.

Most of the scenes are clearly things that Goya himself witnessed (or at least heard about)—the piece titled For a Clasp Knife, for instance, shows a garroted priest with a note pinned to his chest, describing the nature of his crime, referenced in the title. Almost every piece in this series, minus a few more allegorical/fantastical pieces, are artistically rendered acts of war correspondence.

This is Worse is the goriest picture in the series, and the most affecting—a massacred Spaniard has been placed on a gnarled tree stump, his anus and shoulder pierced by broken branches, pinning him in place like a side of meat in a butcher’s window. The dead man’s head is turned toward the viewer, mouth open as though wailing yet not detracting from the stark realism in the piece. Behind this foreground scene, French troops conduct further atrocities.

The scene is based on an event in 1808 near Chinchón, Spain—French troops retaliated for the killing of two of their number by local rebels by massacring the men of Chinchón. If you ever wanted to know the true horrors that can occur in war without witnessing it yourself, this series, and this picture, in particular, can get you close. Be warned.[5]

5 The Various Paintings Concerning John the Baptist’s Beheading—Caravaggio (1607-1610, Oils)

For those of you who prefer your Bible stories acted out by animated fruit and veg, don’t seek out these paintings…or go on the internet ever, for that matter!

Caravaggio, that crazy murderous Italian who just so happened to be one of the most transcendently talented artists ever to have put brush to canvas, knew how to work a miracle. To be able to simultaneously horrify and delight in one work is a skill far beyond most artists. These works, all depicting one Biblical scene, are stunningly beautiful. And chillingly gruesome.

Violence and the divine go hand-in-hand in these works, bringing the tale to life in a way words simply cannot. Also, one shouldn’t be surprised when learning of the artist’s penchant for brawling, dueling, murdering, and throwing plates of artichokes in tavern owners’ faces. Okay, he only did that once.[6]

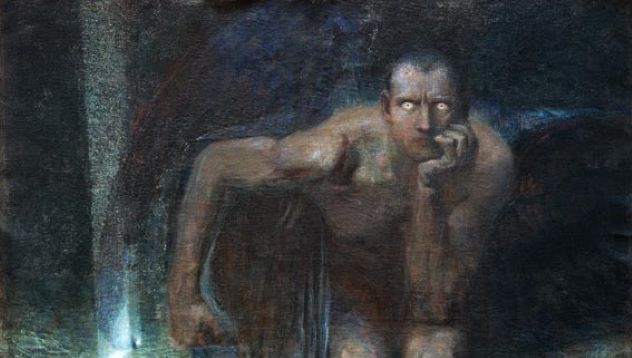

4 Lucifer

Franz Von Stuck (1891, Oil)

The idea of the devil has become sanitized in pop culture over the last 100-or-so years. From corporate mascot for cigarette companies to sympathetic lead character in TV shows and name-checked in thousands of pop songs, Old Nick has become rather cool. Or even kitsch.

Franz Von Stuck’s hypnotizingly stark portrait of Lucifer forces the viewer to really think of the original character himself. Or, rather, the central figure himself demands so, with his bright, staring eyes amongst the painting’s gloom. Imagine being Lucifer, cast down from Heaven, never accepting or understanding his own nature, doomed to be the losing adversary for eternity. The longer you look, the longer you consider this, the more that older concept of the devil begins to re-emerge. This fallen angel is forced to wonder how his fate could be what it is. That is what those eyes portray—madness and futility.[7]

Or is it that he is tempting you to join him in perpetual wonder as to the injustice of existence.

Those eyes.

3 Head of Medusa

Peter Paul Reubens (1617–1618, Oil)

The aforementioned Caravaggio is often considered to have painted the seminal, most horrific depiction of this mythological Gorgon’s severed head.

Wrong, it’s Reubens.

Look at all those damned snakes. You don’t have to be afraid of these bitey little buggers to squirm at the sight of the dripping blood forming into new baby snakes. You don’t have to fear wild animals to be confused about why there are two random spiders and a salamander in the bottom corner. The horrific scene brings new drama to this classic myth—Perseus had to bundle this gruesome, venomous pile of no-thank-you-very-much into a sack. Would you put your hands anywhere near this?[8]

2 Gin Lane

William Hogarth (1751, Etching and Engraving)

If the history of the early 20th century U.S. taught us anything, it is that alcohol prohibition doesn’t work. But earlier works that demonized hard alcohol like Gin Lane made a powerful point about the devil’s mouthwash—it can be ruinous. But far from being a puritanical, preachy song or poem, the etching titled Gin Lane depicts a harrowing scene of degradation and abandon that, if everyone planning a drinking binge was forced to stare at for five minutes before hitting the town, would make you think twice about ordering shots.

It’s a companion piece to another etching called Beer Street; this other print shows happy and hale Londoners enjoying life and working hard. The propagandistic message here is that English ale is nourishing and pure, unlike that corrupting foreign gin.

Gin Lane depicts a terrible scene—death, decay, and debauchery are all acted out by devilish-looking gin-quaffing denizens of London’s St. Giles district. The central image is of a syphilitic prostitute, addled on gin, who lets her screaming baby drop to its inevitable death. The image echoes many real examples recorded during the era—a case from 1734 reported that one Judith Dufour strangled her daughter to death using some newly acquired clothes given to the girl at a workhouse. Dufour stripped her murdered child and sold the clothes for 1s. 4d. (1 shilling, 4 pennies).[9]

To buy gin.

1 The Dead Lovers (aka The Rotting Pair)

Unnamed Master from Swabia/Upper Rhine (c. 1470, Oil)

For centuries, Memento Mori—Latin for “remember that you have to die”—has been a mainstay in European art. Little symbols like skulls or hourglasses found obscured in paintings or on sculptures remind the viewer that while alive, we all await death. This reminder of the ever-presence of our own mortality is also present in this piece.

A bit on the nose, don’t you think?

As opposed to the artfully obscured skull that can only be viewed from a certain angle in Hans Holbein’s famous The Ambassadors, this piece by an unnamed German master slaps you in the eyes. The painting was once an obverse depiction of a handsome young married couple (this painting now resides in the Cleveland Museum of Art in Ohio, U.S.), showing the young pair as rotting corpses, their cadaverous forms getting ravaged by snakes, frogs, and all manner of scavenging beasties. The couple still shows a closeness, even in their decrepit form, highlighting that, as much as we do all eventually die, love is eternal. Could’ve suggested this without painting a wedding gift showing the couple as zombies, mind you. Different strokes, I guess.[10]