History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Most Lucrative Art Crimes in History

Art museums are a criminal’s dream as they house art that is as easy to transport as a piece of paper. Art crime can be a lucrative enterprise with billions of dollars up for grabs yearly, second only to drug dealing. Art theft is one of the world’s most lucrative and common forms of illicit trafficking earning art criminals approximately $9 billion in profits annually.

While the rest of the world sees art crime as thrilling Hollywood blockbusters, it is as true as the smirk on Mona Lisa’s face. Here are ten of the most lucrative art crimes in history.

Related: 10 Incredibly Odd Things That People Have Stolen

10 Panels from the Ghent Altarpiece (1934)

In 1934, two panels of the 15th-century Ghent Altarpiece by Jan and Hubert Van Eyck were stolen on the night of April 10. The thieves sliced the panel vertically in half. The first half was the backside, containing a grisaille painting of Saint John the Baptist. It was left in a checked-luggage department of the Ghent train station as a sign of good faith by the thief who sought a ransom of $22,300 for the other side of the panel that depicted the Righteous Judges.

The suspected thief, Arsene Goedertier, who had sent an anonymous letter asking for ransom, died before revealing the location of the painting. It remains missing. But this was not the first theft of this 12-panel painting. Over the course of its 588-year history, it—or pieces of it—has been stolen on more than a dozen occasions, including by both Napoleon and Hitler

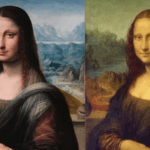

9 The Mona Lisa Theft and Vandalism

Leonardo da Vinci’s painting, the Mona Lisa, is probably the most famous in the world and is known for its reputation for art robbery and vandalism. Vincenzo Peruggia, an Italian carpenter, and two colleagues stole and fled with the painting on a train in 1911. Perugia held on to the painting, putting it under the floorboards of his Paris apartment at one point.

After two years, he tried to sell the art piece to a dealer in Florence in an attempt to bring it back to Italy as a lost treasure. The sale backfired when the dealer called the director of the Uffizi Galleries, who regained the work and called the police.

The second art crime involving the Mona Lisa was in 1956 when a vandal tried to rip the painting using a razor blade. No damage was done to the painting. In the same year, a rock was tossed at the painting by a Bolivian named Hugo Unjaga Villegas. A speck of paint was knocked off from the painting and was later repaired by experts.

In 1974, 25-year ole Tomoko Yonezu, a Japanese woman, tried spraying painting the canvas in red. She successfully sprayed between 20 and 30 droplets of the paint onto Leonardo’s painting, but it was not damaged.

In 2009, a Russian woman smashed a teacup against the painting because she was denied French citizenship. But Mona Lisa was not damaged.

Lastly, in 2022, Mona Lisa was caked during protests against climate change by a 36-year-old man disguised as a woman in a wheelchair.

8 Canada’s Largest Art Heist Involving 18 Paintings (1972)

This heist could be compared to a Hollywood thriller. Thieves entered the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts at 2 am through the skylight. They bound and gagged three guards and made off with 18 paintings and 39 pieces of jewelry. The stolen art included works by Rubens, Rembrandt, and Delacroix. The museum had been doing repairs on the skylight, so it’s possible that the thieves were studying the museum, looking for the best point of entry. They stole around $2 million worth of art.

At that time, the Rembrandt alone was worth one million dollars. You can imagine the worth of the paintings today because, by 2003, the Globe and Mail estimated that the Rembrandt painting was almost 20 times its worth in 1972. They also suggested that the Montreal mafia could have been involved in the heist.

The paintings have never been found.

7 The Storm on the Sea of Galilee

The Storm on the Sea of Galilee by Rembrandt van Rohn is believed to be Rembrandt’s only seascape depicting Jesus and the miracle of calming the Sea of Galilee. Rembrandt painted The Storm on the Sea of Galilee in 1633, and it is one of the most valuable missing artworks in the world.

The FBI claimed in 2013 that a gang and not one person conducted the theft. However, there has been no announcement since then concerning the art piece. A $5 million reward has been placed for information leading to the recovery of the painting.

6 Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (1990)

Thirteen masterpieces worth half a billion dollars were stolen on March 18, 1990, by two thieves disguised as policemen at Isabella Steward Gardner Museum, Boston; the heist remains the largest unsolved art crime in history, three decades later.

The two thieves stole the works by Edgar Degas, Jan van Eyck, Vermeer, and Rembrandt within 81 minutes. The Concert, painted by Vermeer in 1664, was one of the paintings stolen. The piece’s value was estimated at $200 million, and it holds the record of the world’s most valuable and unrecovered artwork.

All attempts to capture the thieves have not been fruitful, and the museum put out a $10 million reward for any information that could lead to the recovery of the art pieces. The combined value of the missing artwork has been approximated at $1 billion.

5 A Benvenuto Cellini Masterpiece (2003)

Renaissance master Benvenuto Cellini’s The Saliera, a 1543 golden sale cellar sculpture featuring land and sea, was removed from its case at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna in 2003. The process set off an alarm misconstrued by a security guard as an accident.

The worth of the art piece was valued at $60 million by Wilfried Seipel, the museum’s director at the time, who termed the theft a catastrophe. Robert Mang, a security expert, was found to be the thief in 2006 after he made two attempts to receive $12 million in ramson for the artwork.

4 J.M.W Turner Paintings (1994)

Although insurance is never an interesting topic for an art museum, it played a major role in this heist. In 1994 two J.M.W. Turner paintings were stolen at Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt while on loan from the Tate Britain.

Frankfurt police had caught and charged the art thieves, but the men had no information about where the art currently was. The art was insured for 24 million pounds, and the Tate was paid out their insurance claim. As a true power move, the Tate repurchased the rights to the lost Turners in hopes that when the art was found, they would be the rightful owners of the art.

Eventually, the Tate paid various “fees” for information about the missing Turners. And in 2000 and 2002, the Tate finally had both Turners back in their hands.

3 Van Gogh’s Still Life in Giza (2010)

The Mohamed Mahmood Khalil Museum in Giza, Egypt, held the 1887 still life of Vincent van Gogh’s Poppy Flowers. Although it was next to impossible to steal the artwork, in 2010, the museum received only nine visitors when the artwork was cut from its frame and removed from the institution.

The theft’s success was helped by the painting’s alarm and other alarms in the museum that did not work that day. The painting is said to be worth between $50 million and $55 million. The piece is still missing to this day.

While some people engage in art crime for its thrill, it can also be lucrative, earning the individual hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars. However, institutions, government authorities, and collectors are collaborating to curb art crimes.

2 Art Forgery

Art forgery is a multimillion dollars enterprise. As a result, more people are passing off work as the production of other people. Forgery is enabled by the unavailability of dating and authentication methods to potential buyers and dealers. Then you have the really good forgers who are even fooling the experts. Without the proper protocols and personnel in place, art forgery will always be common.

Some common forgery prey include Dalu, Picasso, Matisse, and Klee because of their artwork’s intense popularity and prolific output. Forgers intentionally incorporate hidden messages or flaws that protect them from future forgery claims. Forgers have been known to earn enough notoriety that their fakes become high-priced collectibles on their merit alone.

Michelangelo started selling “Roman antiquities” he carved, aged, buried, and then ostentatiously dug up. He got caught when he sold a fake cherub to the Pope’s nephew, but his work was so good, and he was already well-known, so rather than paying the piper, it turned into a succès de scandale and helped his reputation.

1 Fraud

The art industry is poorly regulated, making it easy to get away with slimy scams. Larry Salander, a former New York City gallerist, was recently sentenced to a six-to-18-year prison term for defrauding investors, artists, and clients.

It is believed that he gained approximately $120 million using various tactics such as selling unauthorized works, providing false sales information, neglecting to inform consigners when a sale was occurring, and securing loans and retaining payments rather than transmitting them.