Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

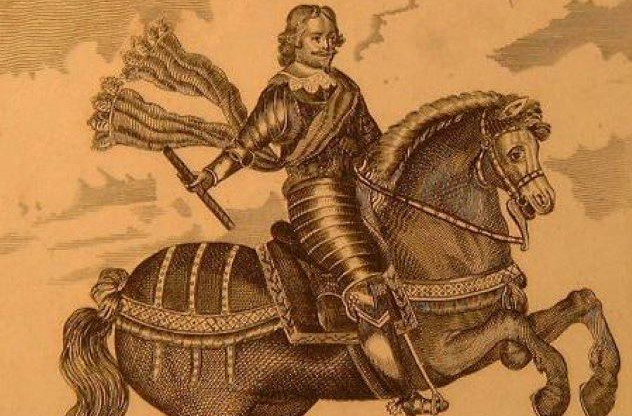

10 Truly Hardcore Scottish Mercenary Fighters

Colombia, Poland, Venezuela, Ireland, Sweden, Morocco—the list goes on. For hundreds of years, Scottish soldiers have taken the opportunity to earn money by fighting in foreign lands. In other words, they were mercenaries. Sometimes these Scottish soldiers of fortune supported established monarchs, while on other occasions, they fought with rebels anxious to upend the status quo. But wherever they went and whoever they fought, the results most often were tales well worth the telling.

Related: 10 Fascinating Stories From Legendary Mercenaries

10 Peter McAleese

A Glaswegian born in 1942, Peter Maltese led a band of mercenary fighters to Colombia in 1989. McAleese had an impressive pedigree for his role as the commander of a motley bunch of soldiers of fortune. He’d served with Britain’s feted elite force, the SAS. In a documentary film about his life, McAleese reinforced his image as an all-around tough guy, saying, “I was trained to kill by the Army, but the fighting instinct came from Glasgow.”

McAleese left the army in 1969 and drifted into the shadowy world of mercenary fighters, seeing action in African hotspots such as Angola and what was then Rhodesia and is now Zimbabwe. But why did he travel to Colombia? In a barely credible turn of events, he’d been hired by the Cali Cartel to kill the leader of its main rival, the Medellin Cartel. In other words, McAleese’s mission was no less than to assassinate Pablo Escobar. The Scotsman and his buddies were to helicopter into Escobar’s compound. But McAleese’s chopper crashed in the Andes, injuring him badly. The plot was aborted. McAleese escaped and died in 2021, aged 79. Escobar was killed in a gun battle in 1993.[1]

9 Gregor MacGregor, Prince of Poyais

Born on Christmas Eve 1786, Gregor MacGregor launched his military career conventionally enough by joining the British Army’s 57th Foot Regiment while still only a 16-year-old. The young man saw action in the Napoleonic Wars and eventually attained the rank of major before hanging up his sword in 1810. For his next adventure, his eyes turned to South America, and he arrived in Venezuela in 1812.

MacGregor was acquainted with the revolutionary leader General Francisco de Miranda, who accepted him into his forces as a colonel in the fight against the Spanish colonialists. MacGregor, who had awarded himself a knighthood, rose to be a general in the Venezuelan Army. His exploits included an attempt to seize Florida from the Spanish and a bid to found a colony in Nicaragua.

His most grandiose scheme, however, saw him taking the title of Prince of Poyais as he developed a colony in the Bay of Honduras. To do so, he enticed gullible British investors and prospective colonizers with false claims. They lost all their money, and the colony was a total disaster. Somehow, “Prince” Gregor walked away unscathed.[2]

8 Patrick Leopold Gordon of Auchleuchries

Born in the northeast of Scotland in 1635, Patrick Gordon first left his native land while still a teenager. He traveled to the Polish city of what was then Danzig and is now Gdańsk, where he enrolled at a Jesuit college. A war between Poland and Sweden erupted in 1655, and that was when the young Gordon first became a mercenary. It seems he was none too choosy about who his employers were since he fought on both sides during the hostilities.

In 1661, Gordon walked away from both Poland and Sweden, electing to join the Russian army. With the rank of major, he gave useful service in 1661 by crushing civil disturbances in Moscow. After Peter the Great came to power in 1696, Gordon became a key adviser and even friend to the young Tsar, earning the rank of general. He played an important part in suppressing an attempted palace coup against Peter in 1698. He died a year later.[3]

7 James Francis Edward Keith

Keith was a high-born Scot, the second son of the 9th Earl Marischal of Scotland. Despite that, he was forced to leave his homeland after becoming involved in the unsuccessful Jacobite attempt to seize the British throne in 1715. Fleeing to France, Keith ended up in Spain, where he became an officer in the Spanish Army. But since he was a Protestant in a Catholic country, his prospects were poor, so he left for Russia.

In 1728, Keith was made a colonel of a Russian regiment and fought against the Swedes. After his time with the Russians, it seems that Keith was keen for new pastures, and he joined the Prussian Army, seeing extensive action in the Seven Years’ War that convulsed much of Europe and North America. By now a Field Marshall, Keith fought at the 1758 Battle of Hochkirch in Germany when 80,000 Austrians faced 31,000 Prussians. The Austrians routed the Prussians killing 9,000 of them, including Keith.[4]

6 Archibald Ruthven of Forteviot

Archibald Ruthven was born into a distinguished Scottish family—his father was Lord Ruthven. In 1572, Ruthven sailed for Scandinavia, where he accepted a post in the army of the Swedish king, Johan III. Johan’s first order was that the Scot should return to his homeland to recruit 2,000 mercenaries. In the event, he returned to Sweden with nearly 4,000 soldiers.

Ruthven became embroiled in a bitter dispute about his soldiers’ pay which resulted in the execution of one Scottish officer for embezzlement, Hugh Cahun. Before he was put to death, Cahun accused Ruthven, baselessly as far as we know, of plotting the assassination of King Johan. Apparently in the clear, Ruthven now sailed for Livonia on the Baltic Sea with his troops. There, a bitter dispute with their German allies resulted in the deaths of some 1,500 men. The upshot of this deadly squabble was that Ruthven was again accused of plotting against Johan. Despite his denials, the unfortunate Scot was imprisoned and died in jail.[5]

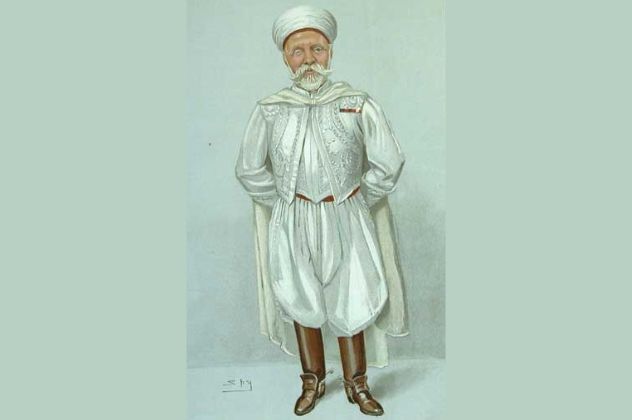

5 Sir Harry Aubrey de Vere Maclean

Born into a well-to-do Scots family in 1848, the splendidly named Sir Harry Aubrey de Vere Maclean joined the British Army in 1869 and saw service in Canada, Gibraltar, and Bermuda. After seven years in the army, Maclean resigned his commission and accepted the position of a drill instructor in the army of the Sultan of Morocco, Mawlay Hassan.

Not long after he arrived in Tangier, Mclean took command of 400 infantry troops, with an increase in pay dependent on him learning Arabic, which he did. Abdul-Aziz succeeded Hussain as the sultan and retained Mclean’s services, sending him on missions to various Moroccan provinces. But life in Morocco was not without its perils; in 1907, the Scotsman was kidnapped and held for ransom for seven months. The following year Abdul-Aziz was deposed by his own brother Mawlay Abdul-Hafiz. The new sultan was minded to keep Mclean on, but the two couldn’t agree on a contract, so Mclean resigned, living out his days in Tangier until his death in 1920.[6]

4 Peter Duffy

Raised in the northern Scottish town of Elgin, Peter Duffy was born into some privilege in 1941. He was sent to Gordonstoun, the same private school that King Charles attended a few years after. Later in life, Duffy was second-in-command of a group of mercenaries who went to engineer a coup in Seychelles Island in 1981.

Duffy’s commander was “Mad” Mike Hoare, a notorious mercenary of many years. Hoare and Duffy led a group of fighters drawn from ex-Rhodesian soldiers and ex-South African special forces. Armed to the teeth, the men flew into Seychelles aboard a commercial flight. Unfortunately for Duffy and his comrades, an airport official noticed an AK-47 in one man’s luggage. A gunfight ensued, and Duffy and others made good their escape by hijacking an Air India plane, leaving behind one dead comrade. Several of the conspirators were tried the next year in South Africa. Duffy got five years, Hoare 10. Duffy died a broken man in 1981.[7]

3 George Sinclair

In 1612, Captain George Sinclair sailed from Scotland with a troop of Scottish mercenaries that he’d recruited in Caithness in the Scottish Highlands. They were to join the cause of King Charles IX of Sweden, who was fighting his neighbor Christian IV of Denmark. Sinclair and some 300 men landed in Norway with the intention of marching to Sweden.

The Scots had not bargained for the possibility that the Norwegians might not take kindly to a mercenary force tramping across their country. As it happened, the Norwegians were not at all happy. Seven days after Sinclair and his men had arrived on Norwegian soil, a local force launched a deadly ambush. As the Scots entered a narrow valley, the Norwegians rolled boulders down the slopes to block their escape routes. Once the rocks had been unleashed, musketeers picked off the mercenaries, killing more than 150. Sinclair was shot dead by a man named Berdon Sejelstad. The Scotsman’s wife and child, who had unwisely accompanied the ill-fated expedition, were also killed, although not before the woman had stabbed one of the Norwegians to death.[8]

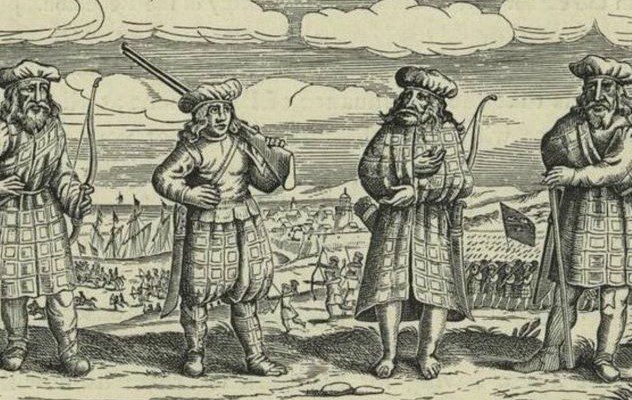

2 Redshanks

The Redshanks were mercenaries mostly recruited from the islands of the Hebrides off the coast of northwest Scotland, although mainland Highlanders joined in as well. In the 16th century, they went to fight for the Irish as they opposed the English invaders of the Emerald Isle. Life in the Highlands and islands of Scotland could be very tough, and men were glad to earn money paid to those who fought for Irish lords.

In one case, a regiment of Highland fighters came as a kind of wedding present. That was in 1569 when the Scottish Lady Agnes Campbell, daughter of the Earl of Argyll, married the Irish nobleman and chief Turlough Luineach O’Neill. She brought 1,200 Scottish mercenaries to the marriage. Unsurprisingly, the English were none too happy about the continual influx of Highland warriors arriving in Ireland. From the late 16th century, the English authorities began to pay off Highland clan chieftains. The payments—bribes might be the correct word—were made on the condition that the chiefs kept their men at home.[9]

1 Alexander Leslie of Auchintoul

Alexander Leslie of Auchintoul was born into a landowning Scots family in 1590—Auchintoul is in the northeast of Scotland. Leslie started out fighting for the Poles in 1618 when he was captured by the Russians. They released him, and by 1629, he was employed by the Swedes. The Swedish king, Gustav II Adolf, sent him to Moscow, and Leslie tarried there in the service of the Tsar.

The Smolensk War, a conflict between Poland and Russia, broke out in 1632, and Leslie brought regiments of mercenaries from European countries, including England and Scotland, to fight for the Tsar. Returning to Scotland in 1637, Leslie embroiled himself in the Civil War of the time, on the wrong side. Captured in battle in the Scottish Borders, he narrowly escaped execution, the fate of many of his comrades. However, he was banished and never allowed to return to Scotland. Leslie returned to Russia, where he achieved the rank of general, the first Scot to do so. His achievements included seizing Smolensk from Polish control in 1654.[10]