Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

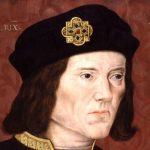

10 Depressing & Tragic Facts about England’s Youngest King

At the age of nine years and three months, Edward VI was crowned King of England at Westminster Abbey. He reigned for six years under the guidance of a Privy council and Lord Protector and was a zealous Protestant king determined to enforce his father’s vision of the Church of England. He died at only fifteen years old and is mostly remembered as a weak and sickly king. That isn’t entirely true, but there are certainly some unfortunate circumstances in his life.

Maybe you’ve read The Prince and the Pauper, and yes, Mark Twain was writing about the boy who eventually became Edward VI, but no switching of identical boys ever took place as far as historians are aware. Whether the real Edward would have been anything like the one in the book is unlikely. However, the riches and doting the prince encountered were certainly real. Of course, being royalty has its perks, but no life escapes sadness, and Edward had plenty of tragedies of his own.

Related: 10 Royal Mysteries Solved by Science

10 Ascended the Throne at Age Nine

Edward was the youngest king to take the English throne at the time of his coronation, and he continues to hold that role to this day. For any regular nine-year-old boy, ruling an entire country might seem a difficult task, but for Edward, well… it was undoubtedly too difficult a task. So a council was set up to help him make decisions and, in most cases, deal with issues on his behalf. He had been a pampered child, and being Henry VIII’s long-wished-for male heir meant he was prepared for the throne from birth. His father referred to him fondly as “this whole realm’s most precious jewel.”

The pressure had certainly been mounting for the nine years leading up to little Edward’s reign, and this was a special situation among Tudors. All the Tudor monarchs before and after Edward had gained the throne by circumstance rather than birth. Henry VII was a usurper who won the crown in war, and the rest became monarchs due to the death of a sibling. In Edward’s case, he was born the heir to the throne and stayed that way until his eventual succession to that throne.[1]

9 Prepared to Be a Copy of his Father

Due to his youth and his father’s strong and unwavering political views, Edward VI would turn out to be an extremely zealous version of his father’s philosophy. This was intentional on Henry’s part, and everything about Edward in his childhood—from his studies to the decorations in his apartments all the way to the very clothes Edward wore—were copies of his father’s. He practiced the same sports Henry VIII is known to have excelled in and was given a strong education in evangelical Protestantism.

It all worked out so that as king, Edward had such a passion and devotion to the Protestant cause that he worked tirelessly to further the success of the Church of England; he published The Common Book of Prayer and issued bans on several traditional Catholic principles.[2]

8 His Father’s Will Left Room for Manipulation

A boy king could not rule on his own, and Henry VIII was well aware of that fact. Rather than appointing a single regent to rule on Edward’s behalf, Henry put into place a council of sixteen men in his will who would fulfill that role. Some sources suggest this final will was heavily doctored and contained a fake signature, with the purpose of removing some of the more religiously zealous council members. It also had two clauses that gave extremely generous rights to the executors of his will, one of which provided for “unfulfilled gifts” to be honored.

In the end, the sixteen men appointed as Edward’s council made allowances for changes to its structure, leading to the rise of Edward Seymour as the king’s “protector.” Seymour, Edward’s maternal uncle, was eventually removed and executed for his manipulations, but not until many years down the road.[3]

7 His Mother Dies When He Was Two Week Old

Edward’s mother, Jane Seymour, the third wife of Henry VIII, died only twelve days after the birth of her son. Initially, she seemed to be recovering well and spent the night following her son’s birth signing announcement letters. She was also seen sitting up in bed hosting the guests of Edward’s christening. With no apparent complications from delivery and a healthy child to show for it, the doctors were quite surprised when four days later, she became pale and weak through the night. Despite this surprising dip in health, she recovered quickly and didn’t experience illness again until three days later. At that point, she deteriorated continuously until her death in the early hours of October 24, 1537.

It is unclear what illness Jane Seymour succumbed to and how Edward eventually felt about the loss of his mother. However, Jane is sometimes considered Henry VIII’s favorite wife (due to her providing a male heir). With that in mind, Edward would likely have had a great fondness for his mother, perhaps influenced by his father’s fondness for her.[4]

6 Edward Had a Fierce and Terrifying Temper

Edward was spoiled severely in his childhood, with constant gifts, rich foods, and everyone in his household doting on him constantly. His father even gifted Edward his own troupe of minstrels with the sole purpose of entertaining him. It might have seemed that nothing he touched, from his cutlery to his schoolbooks, was second-best. He was spoiled to such a point that if he didn’t get his way, the ensuing rage could be incredibly violent. A contemporary account claims that in one such fit, Edward tore a living falcon into four pieces.

Edward started keeping a diary of his innermost thoughts and desires. One entry referred to when he ordered his uncle beheaded, simply stating, “The Duke of Somerset had his head cut off upon Tower Hill between eight and nine o’clock in the morning.” Cutting off his uncle’s head warranted little more notice than a haircut.

But Edward’s diary revealed more than just his cold reaction to his uncle’s execution. Edward VI’s diary provides insight into the kind of man he was becoming—and it wasn’t looking good. The entries reveal a cold, unfeeling boy with almost no emotion at all. Who knows the man and king he would have become had he lived to fully take the reigns of power. Thankfully, we don’t have to think about that.[5]

5 His Relationship with His Sisters Was Complicated

Edward VI had two sisters, both of whom eventually became queens. Mary, the oldest, and twenty-one years his senior, apparently loved Edward dearly and showered him with gifts and affection, even acting in a sort of motherly role. Around the age of nine, he wrote to her that she was his favorite. On the other hand, Elizabeth was only four years older than him, and they had a meaningful childhood bond. Upon learning of their father’s death, Elizabeth and Edward held each other and cried intensely.

However, all this tenderness quickly evaporated when Edward became king, and he focused on having a “kingly” relationship with them rather than a brotherly one. Mary was staunchly Catholic, and this led to dramatic arguments over religion. It became such an issue that Edward decided to write his sister Mary out of the succession. Unfortunately, to remove Mary from the succession on the simplest grounds of legitimacy, he also had to name Elizabeth illegitimate. This went on to cause the succession crisis of 1553 and the death of Edward’s designated heir and cousin, Lady Jane Grey.[6]

4 Edward Had Two Power-Tripping Protectors

Following the arrangement of the council acting for Edward’s regency, the Duke of Somerset (Edward Seymour) emerged as a leading figure and was appointed Lord Protector. Seymour was Edward VI’s uncle through Jane Seymour and was a strong campaigner for more extreme reforms. He desired to break as far away from Catholic tradition as he could go and made intense, sweeping moves against established practices. However, his views led to some groups taking it too far, resulting in rebellion. His failure to stop the uprisings, weakness against his enemies, and lack of military prowess led to his downfall.

One of Seymour’s main opponents, John Dudley (later the Duke of Northumberland), led the demand for his removal. It was Dudley who eventually took over the role of Lord Protector. He wasn’t any better, and in fact, history often refers to him as much worse (he is sometimes called “The Wicked Duke”). Dudley arranged for a sickly Edward to name Lady Jane Grey his heir. After Edward’s death, he even married his boyish son to Jane in the hopes of becoming the father-in-law and controller of England’s first Queen Regent.[7]

3 Edward’s Terrible Illness and Death

In the spring of 1553, Edward contracted measles. He recovered, but his immunity was greatly weakened, and he eventually came down with what historians presume to have been tuberculosis. By May 1553, he was extremely ill, and the Duke of Northumberland acted quickly to ensure his benefit from the succession. On July 1, 1553, Edward was seen in public for the last time, although he appeared extremely thin and “wasted.” He was undoubtedly in immense pain, as at the beginning of July, he whispered the words, “I am glad to die.” On the 6th, he died, and a surgeon who opened his chest after his death declared it was due to a lung disease.

Although this illness lasted barely more than a year, Edward fought the entire time to remain an effective ruler. Whether this was successful is up for debate. Still, his weakness in the final month or two of his life (and ensuing manipulations of Northumberland) ended up setting the stage for a catastrophic succession crisis.[8]

2 His Father’s Will Complicated Edward’s Own Last Wishes

The Succession Act of 1544 allowed Henry VIII to detail in his will any heirs he desired, meaning that although he had declared his daughters Mary and Elizabeth illegitimate, he had the lawful right to name them his heirs, which he did. First would come Edward, then Mary, then Elizabeth, and then a list of other potential heirs (the next four of whom were also women!).

When Edward was about to die and Mary to succeed him, he and his counselors found it very undesirable for a Catholic monarch to take over and erase all his years of Protestant reform. To counter this, Edward wrote his sisters out of the succession in his will and named his cousin Lady Jane Grey heir. Then ensued that succession crisis we’ve been talking about!

In July 1553, Lady Jane was named Queen of England, but only a short while away, so was Mary. The wills of two dead kings were at odds, with Mary claiming legitimacy from her father’s will and Jane claiming legitimacy from her cousin’s. Ultimately, Henry’s will and Mary’s public support and military power ended up putting her on the throne, and Jane lost her head.[9]

1 England’s Return to Catholicism (Temporarily)

Two weeks after the death of Edward VI, and at the age of 37, Mary Tudor became Mary I and began the process of returning England to the Catholic Church. She is often remembered as “Bloody Mary” for her extreme actions in doing so. But she, in fact, killed far fewer people than Henry VIII.

Edward would likely have been devastated to know his careful preparations for keeping England a Protestant nation, as his father had wished, had failed. But this didn’t last long, and only six years later, Elizabeth succeeded her sister as Queen, and again England switched. Eventually, the Act of Settlement in 1701 would mean only Protestants could claim the English and Irish crowns.[10]