Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Widespread Historical Myths and the Texts That Started Them

Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

Technology

Technology 10 Unsettling Ways Big Brother Is (Likely) Spying on You

Music

Music 10 Chance Encounters That Formed Legendary Bands

Space

Space 10 Asteroids That Sneaked Closer Than Our Satellites

Sport

Sport The 10 Least Credible Superstars in Professional Sports

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 of History’s Greatest Pranks & Hoaxes

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Widespread Historical Myths and the Texts That Started Them

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

Technology

Technology 10 Unsettling Ways Big Brother Is (Likely) Spying on You

Music

Music 10 Chance Encounters That Formed Legendary Bands

Space

Space 10 Asteroids That Sneaked Closer Than Our Satellites

Sport

Sport The 10 Least Credible Superstars in Professional Sports

Top 10 Corpse Medicines That Turned Patients Into Cannibals

From classical Rome to the 20th century, corpse medicine, or medicinal cannibalism, was rampant throughout all levels of European society. Consumption of extracts and concoctions from human brains, flesh, fat, livers, blood, skull, bone, hair, and even sweat were swallowed and topically applied by monarchs, popes, intellectuals, and the everyday person. Writers like Shakespeare wrote about it, physicians prescribed it, apothecaries sold it, and one king made it, while another king ended up as corpse medicine. Europeans could not get enough of it.

Body parts for corpse medicine became a booming business for executioners who would often strip the flesh, bone, blood, fat, and other bits to sell to the clamoring crowds immediately following the execution. Traders supplied corpses from far-flung countries, while gravediggers dug corpses up in the middle of the night to sell to physicians.

As strange—and disturbing—as it sounds, there was a philosophical underpinning to this macabre practice: the consumption of the body meant absorption of the power of the soul and the base essence of creation according to alchemists. Each concoction was touted as a miracle cure, and each was as ghastly as the other.

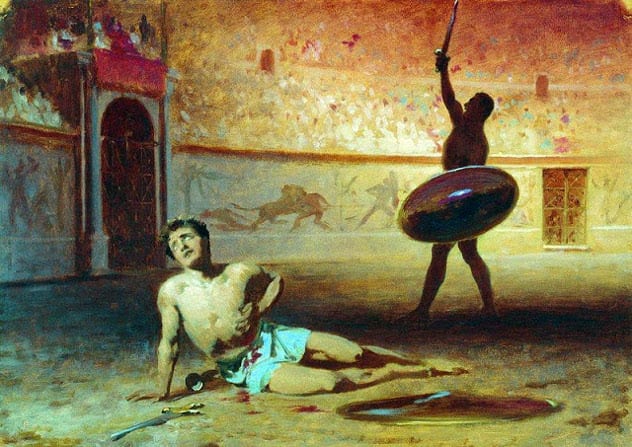

10Gladiator Blood and Liver

Slain gladiators turned the arena from a blood sport into blood medicine during classical Rome. Romans believed they could absorb the gladiator’s vitality and valor by drinking their hot blood.

Epileptics would crowd a fallen gladiator and suck the “living blood” from his open wound. Roman physician Scribonius Largus went to great pseudoscientific lengths to suggest that the liver of a stag killed by a weapon used to vanquish a gladiator could be a magical cure for epilepsy.

It was not long before simply eating the liver of a gladiator was deemed to hold similar curative effects. When gladiator matches were banned in A.D. 400 epileptics found a new blood source at executions.

9Blood of a King and Other Criminals

The idea that epilepsy could be cured by the still-warm blood of the deceased lingered well on into the late 19th century. Crowds of epileptics used cups to catch the blood of freshly decapitated corpses at Scandinavian and German scaffolds. In one account from early 16th century Germany, an impatient member of the crowd snatched a corpse and drank the blood straight from its severed neck.

Consumption was not limited to the blood of common criminals. On January 30, 1649, Charles I of England, was beheaded for treason. Crowds rushed forward and washed their hands in the King’s blood. A monarch’s touch was thought to cure the “king’s evil,” which was the name given to swollen lymph nodes caused by tuberculosis, but it seems his blood was even better. After Charles I lost his head, the enterprising executioner reportedly made money auctioning off blood-soaked sand and bits of Charles’s hair.

8The King’s Drops

While Charles I became corpse medicine, his grandson, Charles II, made his own. Apparently a skilled chemist, Charles II bought the recipe for a popular tincture called “Goddard’s Drops” and made it in his own laboratory. Jonathan Goddard, the physician who invented it, reportedly earned a handsome fee of £6,000, and for close to two hundred years the tincture became popularized as “the King’s Drops.”

The recipe was suitably vile: two pounds of hartshorn, two pounds of dried viper, two pounds of ivory, and five pounds of a human skull. The ingredients were minced and then distilled into the final liquid form. The human skull was the active ingredient and had an important spiritual purpose. Alchemists reasoned that a sudden, violent death trapped the soul within human remains, including the skull. Thus, consumption gave the recipient the vital life force of the deceased.

The King’s Drops’ success as a so-called miracle cure of nervous complaints, convulsions, and apoplexy is somewhat dubious. Instead, it could be deadly. Documents show that it knocked off a few important people. In the case of the English MP, Sir Edward Walpole, the King’s Drops brought on convulsions rather than cured them. Walpole was described as “the saddest spectacle” as he succumbed to the potency of the King’s Drops.

It seems that its only medical success was as a stimulant. Distilled hartshorn turns to ammonia which was a key ingredient in smelling salts. But most of the time, the King’s Drops just appeared to have little effect. On February 6, 1685, Charles II had it hastily administered to him on his deathbed to no avail.

Despite this, the King’s Drops remained popular with the privileged and lower classes. It even appeared as a medical recipe in the cookery book The Cook’s Oracle (1823), which detailed how to distil your home supply of human skull to treat your child’s convulsions.

7Skull’s Moss

The dubious curative powers of human skull extended to the mildew or moss that grew on unburied human skulls. Called usnea, it was found in plentiful supply on exposed skulls on the battlefield. Soldiers met the required violent end needed to maintain the “vitality,” or life essence, within the body. Somehow this soul essence was absorbed into the skull moss under the influence of “celestial orbs.”

Usnea was used extensively during the 17th and 18th centuries. As a powder, people stuffed it up their noses to stem nosebleeds or used it internally for wide-ranging concerns from epilepsy to menstrual problems. The “father of medicine,” Sir Francis Bacon, proposed its use as part of a wound salve to be rubbed on a weapon. The idea was that rubbing the blade of the weapon would heal the wound it caused.

6Distilled Brain Mash

In The Art of Distillation (1651), physician and alchemist John French described a particularly revolting preparation of an equally revolting remedy—brain tincture. In a matter-of-fact way, French lays out the process for aspiring practitioners.

In The Art of Distillation (1651), physician and alchemist John French described a particularly revolting preparation of an equally revolting remedy—brain tincture. In a matter-of-fact way, French lays out the process for aspiring practitioners.

“[T]ake the brains of a young man that hath died a violent death, together with the membranes, arteries, veins, nerves, [and] all the pith of the back,” and “bruise these in a stone mortar till they become a kind of pap.” Once mashed, the brain paste was covered in “spirit of wine,” then left to “digest” in horse poo for six months before finally being distilled into an unassuming liquid. French most probably had a fresh supply of young male heads from his work as an army physician, and plenty of left-overs from dissections done at the Savoy Hospital, where he prepared his brain mash.

Like other corpse remedies, this was not a fad, and references to its use can be found throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. An even nastier version from the 1730s involved the smashing of human brains, hearts, and bladder stones with breast milk and warm blood.

5Human Fat Ointment

Human fat became big business for executioners during 17th and 18th century Europe. In Paris, people would bypass the local apothecaries and line up at the scaffold for their personal jar of rendered human fat. Viewing the dismemberment and carving up of the corpse at least would have reassured the public they were receiving the genuine article, and not some animal fat knockoff. The human grease was touted as a great painkiller for aches, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, and was even used to treat breast cancer.

It was popular among the elites as well. Queen Elizabeth I smeared the unguent of human fat over her face to treat pits left by smallpox. A recipe from the 18th century for human fat unguent describes a pretty toxic ointment of human fat and beeswax mixed with turpentine. There is a distinct possibility that a similar recipe was used by the queen. This, along with her use of lead-based makeup, may have accounted for her death in 1603—rumored to be from blood poisoning.

4Sweat of a Dying Man

English physician George Thomson (c. 1619-1676), was well-known for using every conceivable part of the human corpse, including a prescription of urine for plague, and the consumption of human afterbirth to combat excessive menstrual bleeding. But nothing was weirder than his cure for hemorrhoids. The sweat of a dying man (presumably induced from the terror of the scaffold) could be rubbed over your piles. If the executioner did not have sweat on tap, then the touch of the severed hand from the executed could apparently make your hemorrhoids miraculously disappear.

3Honey Mummy

Mellified Man was basically the art of turning a man into candy. Reported by Chinese physician Li Shih-Chen in his book, Chinese Materia Medica (1597), mellified man was a by-product of an Arabian mummification process. The recipe is simple enough: take one aged male volunteer. Bathe him in honey, feed him nothing but honey (apparently, the volunteer would defecate only honey after a while), then when he dies from this diet, encase and seal him in honey for 100 years.

After 100 years, he would be rock hard candy that would be administered to heal broken or weakened bones. According to one source, this honey mummy confection was available throughout Europe and China. It is difficult to determine for sure, but not a stretch considering Europeans were consuming a mummy of a different kind for over 600 years.

2Mummy Powder

Egyptian Mummy took Europe by storm as a cure for everything and anything including blood clots, poisoning, epilepsy, stomach ulcers, and broken bones. Various products existed: “treacle of mummy,” “balsam of mummy,” tinctures, and its most popular form, mummy powder.

Labeled in apothecaries across Europe as mumia, the powder became a staple medical aid from the 12th century to the 20th century. Early medical texts abound with its prolific use across Europe. Mummy powder is even referenced as a product in the archives of the pharmaceutical giant, Merck.

It was believed mummies were embalmed in bitumen. Bitumen removed from mummies was believed to have medicinal qualities, but it was not long before the flesh itself was considered to carry the health benefits. When supplies of genuine Egyptian mummy ran low, a fraudulent business replaced it. Recently deceased corpses were baked in the sun to age and emulate mummification.

Physicians swore by it, but there was one noteworthy detractor, French surgeon Ambroise Pare (c. 1510–1590) who disparaged mummy powder’s usefulness along with another snake oil of the day, unicorn powder.

1Red Tincture of 24-Year-Old Man

“Mummy” as medicine was eventually extended, legally, to include the flesh of recently deceased men prepared in a kind of pseudo-mummification process. “Red tincture” was a particularly strange version in the recommendation of using a corpse of a specific age and complexion. Developed by German physician Oswald Croll, it soon became a popular remedy used in London during the late 1600s. Translations of Croll’s original work describe how to make it. “Choose the carcass of a red man [ruddish complexion], while, clear without blemish, of the age of twenty-four years, that hath been hanged, broke upon a wheel, or thrust-through, having been for one day and night exposed to the open air, in a serene time.”

The flesh would be cut into chunks, powdered with myrrh and aloe, then softened in wine. Then it was hung up for two days to dry in the sun and absorb the effects of the moon, before being smoked, and finally distilled. Apparently, the stench of the liquid was disguised with the sweet aromas of wine and elderflower.

Daniel is a museum anthropologist and bioarchaeologist who moonlights as a freelance writer.