Animals

Animals  Animals

Animals  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Top 10 Bizarre Uses for Human Skin

Leather—the tanned and cured hides of animals—is a vital component in mankind’s history, from practical uses like shoes, straps, saddles, holsters, etc. to car interiors, handbags, briefcases, hooker boots, and BDSM gear (I’m looking at you, Fifty Shades of Grey). The most common leather is cow. The rarest leather is, like Soylent Green, made of people.

Everyone’s heard of books bound in human skin, a staple of horror fiction and supernatural films and TV shows. The practice is called anthropodermic bibliopegy. However, books aren’t the only items on this list. For one reason or another, someone somewhere at some time wanted something wrapped in or made from the skin of hero, victim, killer, or weirdo. You’ll find the top ten of these macabre human leather goods here.

Caveat lector: A few of these items, particularly those pertaining to the French Revolution, are considered apocryphal – likely propaganda – among some historians.

A fifteenth century, undefeated Hussite military commander, Jan Ziska – real name Jan z Trocnova – wouldn’t let a little thing like dying bring an end to his Protestant uprising against the Catholic church. He’d already led his forces into battle to whip the Holy Roman Emperor’s armies, invaded Austria and Moravia, and participated in a civil war even after losing both his eyes! Legendarily, when he lay dying from the plague while on the march to Bohemia, Ziska ordered that after his death, his body should be flayed, and his skin cured and stretched over a drum to continue terrifying the enemy on the battlefield with his sheer badassery.

During the Reign of Terror in an eighteenth century France torn apart by revolution, Saint-Just rose to become a political leader, military commander, and close friend of Robespierre as well as a member of the Committee of Public Safety, which condemned quite a few people to the guillotine. In a story attributed to de la Meuse’s “Anecdotes”, Saint-Just’s romantic advances toward a tall, young, beautiful woman were spurned. In a hell-hath-no-fury moment of madness, he had her arrested, executed, her skin removed by a surgeon, cured by a tanner, and made into a fashionable waistcoat which he wore every day. Another version of the story is that the woman was a thieving maid who got her just desserts.

Henri Pranzini, the late nineteenth century French conman-turned-murderer – nicknamed the “Splendid Darling” – made a splash in more ways than one. He trial caused a worldwide sensation, and he ended his days with a visit to the guillotine. As a grotesque, unconfirmed, but entirely possible coda, it’s said that bits of his body were sold to collectors hungry for a piece of the infamous killer, including one of his teeth knocked out for a woman who had it set into a ring. The report goes that a member of the Sûretè (secret police) got hold of some of Pranzini’s skin as a souvenir du jour, and had a cigar case made from the leather.

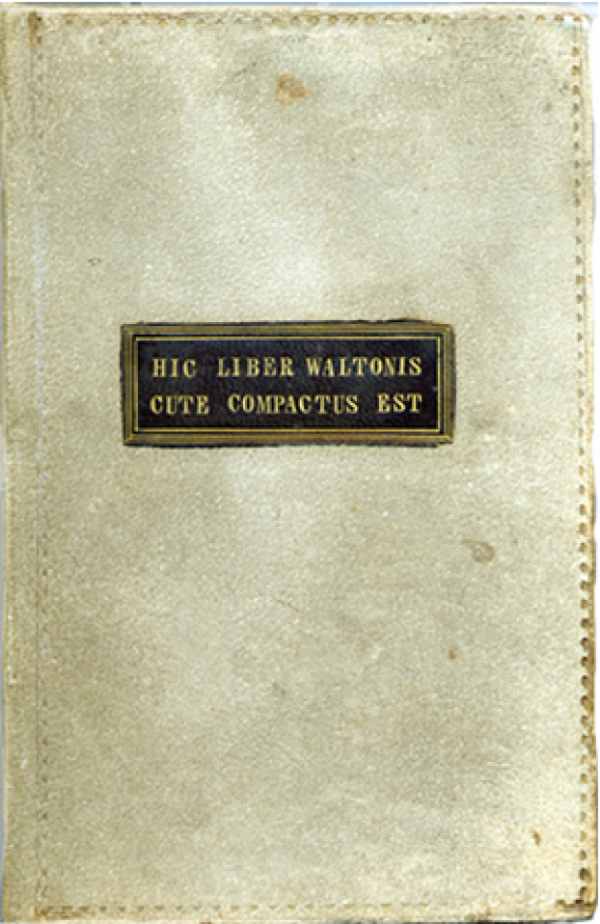

One of the more famous items on this list. Today held in the collection of the Boston Athenaeum library, the book has the title, Hic Liber Waltonis Cute Compactus Est (this book ia bound in Walton’s skin). James Allen – real name, George Walton – was a notorious nineteenth century highwayman who died of tuberculosis while incarcerated in 1837. Before he died, he requested that his skin be removed and used to bind a volume of his autobiography to be presented to John Fenno, a former robbery victim who’d bravely stood up to him after being shot. The book remained in the Fenno family until donated to the library.

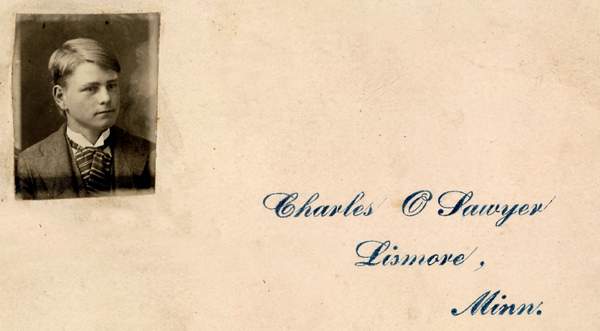

The nineteenth century body snatchers and murderers, William Burke and his partner, William Hare, killed seventeen people in Edinburgh, Scotland, and sold their bodies to a doctor for dissection. Burke was convicted and hanged, but didn’t go peacefully to his grave. His body was dissected – his skeleton and death mask are in the University of Edinburgh’s Anatomical Museum – and other parts of his corpse made into useful items such as the binding of a pocketbook, and a very elegant calling card case made from the skin of his left hand, now on display at the Police Information Centre on Edinburgh’s Royal Mile.

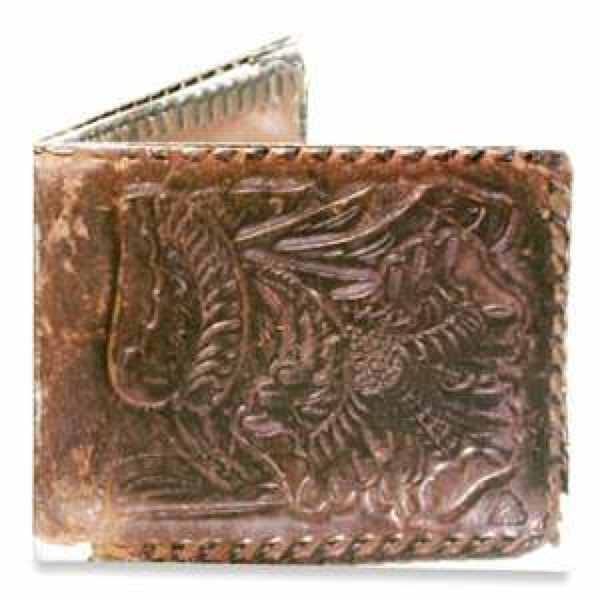

In Morristown, New Jersey, in 1833, French immigrant Antoine LeBlanc battered three people to death, stuffed a pillowcase full of their valuables, and fled the blood splattered scene. He was caught, convicted, and sentenced to hang. The judge also ordered that the infamous killer’s body be dissected after death. According to reports, LeBlanc was flayed, his skin tanned, and some made into wallets and change purses. Other strips of the skin signed by Sheriff Ludlow (the man who’d caught LeBlanc) were sold as mementoes to curiosity seekers. Long considered mere rumor, the stories were proved plausible in 1979 when LeBlanc’s death mask and what appeared to be a human leather wallet were discovered in the house of the town’s unofficial historian and collector of nineteenth century artifacts.

![]()

In this case, the skins’ unwitting donors are unknown. In 1876, Mr. Mahrenholz of H&A Mahrenholz in New York, a shoemaker who enjoyed experimenting on various types of leather including catfish and anaconda, procured the stomach, back, and buttock skins of a pair of unidentified elderly men who’d died and been previously dissected. After tanning the pieces of skin in dog manure and water – yes, there was a roaring trade in dog poop gathered and sold to tanneries, it was called “pure” – he made a handsome display boot and sent it to the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. where it remains in their collection.

Around 1633, the French king Louis XIII founded the Cabinet du Roi, a private museum or cabinet of curiosities at the Palace of Versailles containing some interesting oddities. In the late eighteenth century, it’s reported by Valmont De Bomare in his Dictionnaire that a Paris surgeon, Pierre Sue, donated a pair of slippers made of human skin to the Cabinet du Roi, which already contained a human leather belt (nipple still visible). Eugène Sue, a descendent of Pierre, continued the family tradition by having an 1854 volume of Le Mystères de Paris bound in peau de femme – the skin of a woman who loved him.

A noted Dutch physician and botanist in Leyden in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, Hermann Boerhaave is said to have owned a private collection of curiosities – including what’s been reported as a pair of ladies’ high heeled shoes made from leather obtained from the skin of an anonymous, executed male criminal. The contributor’s nipples were neatly centered on the uppers to form a grisly accent. How Boerhaave acquired this fashionable footwear is not known, but in Notes and Queries Volume II, Series II (1856), Henry Stephens wrote about seeing the shoes himself in 1818.

During the French Revolution, as the story goes, someone noticed that a potentially valuable resource was being wasted – the corpses of people executed by the guillotine. Accordingly, the Committee of Public Safety gave permission to use the castle of Muedon outside Paris as a tannery to process leather from human skin. Quite a number of gentlemen allegedly wore breeches and boots made from the product, which is said to have been supple and high quality. In fact, if you believe the author Montgaillard, men’s skins were preferred for fashion, having the texture of chamois. Women’s skins were too soft to be very useful.

Over the centuries, a few of the deceased have taken on new life by contributing body parts to dentures, fertilizer, fashion, the decorative arts, and other pursuits. Does the thought make you shudder? You’re in good company. The living will probably always have a morbid fascination for objects made from the dead … perhaps a reminder of our own mortality.