Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Of The Strangest Things Beetles Can Do

Beetles don’t only outnumber humans—they outnumber everything. One in every four creatures on Earth is a beetle, and if you throw in plants, beetles make up one in five living organisms. There are an estimated three million species of them, with only about one-tenth identified. We’ve used beetles for some very strange purposes, and some of the insects themselves lead truly disgusting lives.

10Live Beetle Bling

The use of live beetles as jewelry dates back to ancient Egypt, when soldiers wore scarabs—supposedly with magic powers—on their uniforms into battle. In Mexico, an ancient Mayan tradition tells of a princess forbidden to marry her true love. A witch doctor turned her into a Maquech beetle so that she could live out her life on her lover’s tunic, near his heart. Mayan women began wearing live Maquech beetles in honor of the legendary princess.

Live Maquech beetle jewelry has been a fashion trend in Mexico since the 1980s. The adult Maquech does not often feed and usually lives two to three years. Rhinestones and jewels are cemented to the beetle’s forewings (“elytra”) along with a gold chain attached to a pin. It is pinned to the shirt or blouse, and the Maquech wanders freely across the wearer’s chest.

The jewelry is, of course, hotly denounced by animal rights groups. The Maquech also cannot be taken across the border into the US, and travelers can be fined up to $500 if they try.

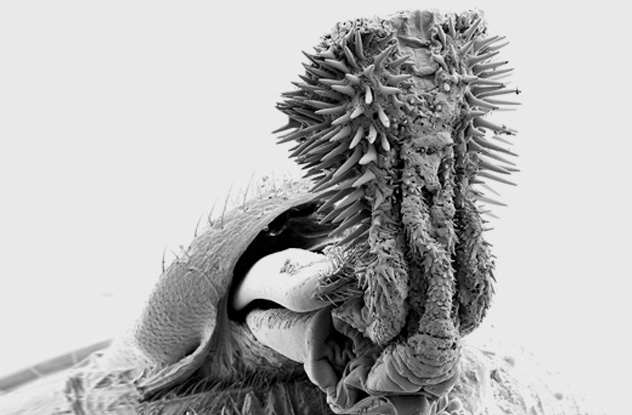

9Spiky Beetle Sex

The female diving beetle’s reproductive tract is a labyrinth. It keeps the sperm of several males alive and inside her for months or even years. This likely allows her body to choose the best sperm for fertilization.

There are about 5,000 species of ladybugs (also called “ladybird bugs” and “lady beetles”). This is apparently confusing to the male ladybug because his aedeagus (penis) will only fit the reproductive tract of a female of his own species, like a key to a lock.

But nothing is scarier than the aedeagus of seed beetles, also known as bean weevils. Their penises are spiked and horned so they can anchor themselves in the female’s reproductive duct. The photo above is an electron microscopic image of a seed beetle’s penis.

Females have developed padding within their ducts to protect them from damage. Some injury, however, does occur, and many scientists speculate that this keeps the female from copulating with another male for a while.

8The Dung Hat

Beetles also extensively use their own feces. The beautiful golden tortoise beetle has an anal fork where feces and dead skin collect into a huge shield shaped like a beaver’s tail. The larvae of leaf beetles have a transparent bubble on their back filled with feces that they carry around to deter enemies.

One of the oddest fecal shields is the one carried by palmetto tortoise beetle larvae, which can be found from Mississippi to Florida, usually feasting on saw palmetto plants. As the larva matures, it spools out its feces into coiled layers that looks like an unkempt Rastafarian hairdo, a bird’s nest, or a straw hat.

7Railroad Worms

Glowworms are not worms but the larvae of several bioluminescent insects. Some are flies or gnats, but the term usually refers to the Lampyridae or Phengodidae families of beetles.

The Lampyridae family, commonly called fireflies or lightning bugs, live in the humid regions of the Americas, Asia, and Europe. They have a dedicated light organ in their abdomens where oxygen combines with luciferin to produce light. A 2010 study found that the light from just 10 fireflies is equivalent to that of a streetlight. Soldiers in World War I trenches used jars filled with European fireflies as lights to illuminate maps and reports.

Female larvae of the Phengodidae family have paired light organs on the side of each body segment, which produce a yellow-green light like coach windows on a train. They also have a bright red light on their head and are thus called Railroad Worms.

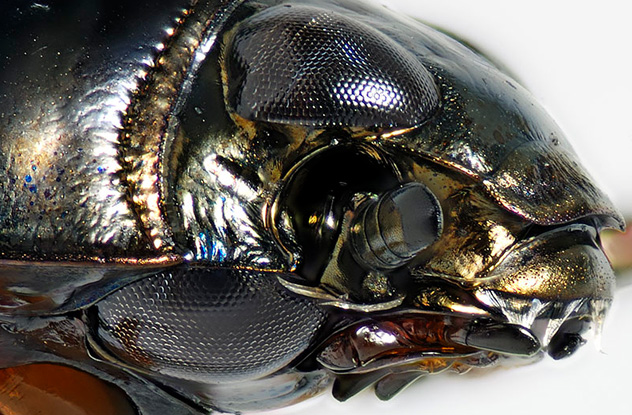

6Beetle Metal

Several beetles are iridescent, giving a shimmering, metal-like look to them and garnering them the title of “living jewels.” The outer surface of these beetles is made of stacks of plate-layers, oriented in different directions to bend and reflect light. Under the plates, a layer of pigment enhances the iridescence.

The genus Spilopyra has some of the most spectacularly hued beetles in the world and is given the rather mundane classification of small leaf-beetles (Chrysomelidae). Unlike many iridescent beetles, members of this genus shine not just on their elytra, but on their head, legs, and even under their belly. One of the most beautiful species in this genus is the rare Spilopyra sumptuosa that hails from Australia and New Guinea. Its colors range between golden-green, purple-blue, and purple-green.

Scientists are not certain why beetles are iridescent. Unlike birds, beetles use chemicals rather than colors to attract mates. Science has determined that the iridescent colors do not advertise a beetle’s presence to predators. They remain remarkably well camouflaged.

5Navigating, Poop-Dancing Beetles

Competition among dung beetles is so stiff that some beetles cling to a mammal’s buttocks, waiting for first dibs on the next load. And once the load drops, the competition grows even fiercer. A beetle could roll itself a nice, tasty ball of dung, only to have it stolen by a marauding neighbor.

It must transport the ball to its burrow, where it can dine and gestate its young. To ensure that the dung rolls in a straight line (to avoid circling around and returning to the poop paddy bedlam), the dung beetle climbs atop its ball and does a little dance. It circles around, finding a bearing, then climbs down and begins pushing (or dragging) the ball with its back feet.

During the day, polarized light appears symmetrically around the Sun. Humans can’t see this, but dung beetles have special receptors in their eyes that allow them to detect it and get their bearing for their dance. At night, the beetles use the fainter polarized light around the Moon. On moonless nights, they use the Milky Way.

4Retro Body Types

Many beetles’ bodies have the same physical structure as their prehistoric ancestors. One family of beetles has developed a body type similar to a fellow arthropod: the extinct trilobite. The female trilobite beetle has a plated, segmented exoskeleton for protection just as the prehistoric trilobite did. Unlike the ancient version, the beetle can retract her miniscule head under her flat armor.

Some have claimed that trilobite beetles are bioluminescent, but they are likely mistaking the beetles with firefly larvae, which have a similar body type. The trilobite beetle’s head is visible, while the firefly larva has a plate covering its head.

The male grows an ordinary beetle body and can fly. The female stays in her larval trilobite form her entire life and is wingless. She is also 10 times the size of her male counterpart, usually 6 centimeters (2.4 in) to his 5 millimeters (0.2 in). The male and female copulate for a full five hours. Then the male dies.

3Beetle Ghouls

The male and female gravedigger beetles spend their honeymoon hunting for just the right dead bird or rodent. They then transport the carcass to a more appropriate locale by carrying it, rolling it, or by lying under the carcass and walking it forward as if on a conveyor belt.

Once they’ve found the perfect spot, they bury the carcass. They dig a hole under the corpse and cover it with topsoil. The male stays above ground, spending his short life guarding the burial plot. Within the grave, the female constructs a brood chamber adjacent to the carcass. She then removes the fur or feathers, debones it, and secretes a preservative to keep the meat fresh.

She lays eggs within the corpse. Once they hatch, the mother eats and regurgitates the carcass meat into the larvae’s mouths. She also carries on her body tiny arachnid mites that feed on fly eggs so that her offspring need not compete with maggots.

2The Better To See You—And You, And You, And You

The whirligig beetle would make James Bond green with envy. It can function as either a motorboat, a submarine, or an aircraft. The whirligig’s family name, Gyrinidae, is Latin for “circle,” and it spends much of its days paddling in circles on the surface of ponds and lakes.

The beetle has four long, orange, flattened legs that can make 60 strokes a second. The beetles gather in groups and move in what appears to be a chaotic way. In reality, each whirligig has a specific placement in the group, and they communicate continuously with one another to maintain that placement.

When frightened, they dive underwater and use an air bubble attached to the tip of their abdomen to stay under for extended periods. In the autumn, the adults fly off in search of another water hole. The close-up of its head looks like the nose of a spaceship. On the head, four compound eyes can be seen, one set on top of its head and one set underneath, allowing it to see above and below the water.

1Spanish Fly

The legendary aphrodisiac Spanish fly is not made of flies but of beetles, specifically blister beetles. These beetles secrete a milky fluid called cantharidin from their leg joints to ward off predators. Females cover fertilized eggs with cantharidin to protect them. Males give the female a packet of sperm to use at her leisure. To make his packet more desirable, he’ll throw in drops of cantharidin.

Cantharidin is a colorless, odorless solid at room temperature. It’s a poisonous irritant and causes blisters if it touches the skin. If swallowed, it can strip the lining from the stomach. It is as toxic as strychnine and has no known antidote.

According to legend, the blister beetle can be ground up and sprinkled into a woman’s drink and to make her feel aroused. In reality, it may kill her. The notorious Marquis de Sade gave prostitutes chocolates laced with Spanish fly. They survived, but de Sade was charged with attempted murder.

Men, on the other hand, can derive at least one benefit from taking Spanish fly. Cantharidin does not lose its irritant qualities as it’s digested. Eventually, it’s excreted in the man’s urine, but as he passes it, his urethra swells extensively. It thus causes a long-lasting, painful erection. He can suffer from extreme abdominal pain, respiratory and heart failure, renal failure, bloody urine, convulsions, coma, and death. But he’ll have that erection.

+George Harrison And The Beetles

Famous guitarist George Harrison famously once said that his biggest break in life was joining The Beatles. His second-biggest break was quitting the band.

Harrison was an avid gardener. After his death in 2001, a pine tree was planted in Los Angeles’s Griffith Park in his memory, complete with a plaque and flower bed. By 2013, the pine tree had grown to 3 meters (10 ft). It was then killed by infestations, probably by Dendroctonus ponderosae or Coccinella magnifica.

That’s right: The George Harrison Memorial Tree was felled by a beetle.

Steve is the author of 366 Days in Abraham Lincoln’s Presidency: The Private, Political, and Military Decisions of America’s Greatest President.