Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

10 Horrifying Torture Devices Used At The Castle Of The Counts

Listverse is in Belgium leading up to the World War I centennial at Flanders Field on October 18, and along the way we’re traveling the country and experiencing everything this incredible region has to offer. Follow along on Twitter or Facebook with the hashtag #LVHitsBelgium.

Gravensteen, or the Castle of the Counts, was built in the late 1100s along the Lieve River in Ghent, Belgium. The castle has served many roles throughout history—the royal seat of the counts, a courthouse, even a textile factory—but in the late Middle Ages it went through its darkest period: a house of torture. We got the opportunity to tour the castle and see firsthand the torture devices still inside.

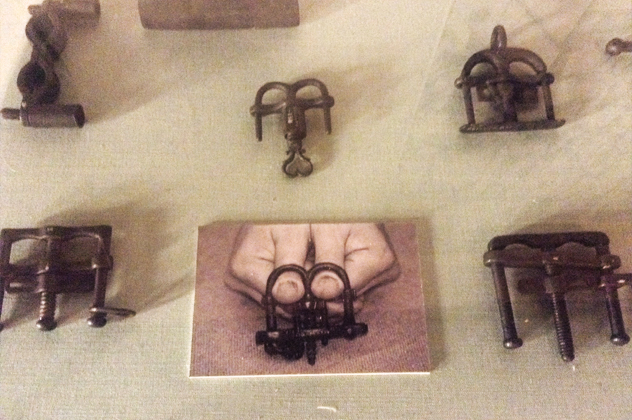

10Thumb Screws

We’ve talked about thumb screws before. When a prisoner in medieval Europe needed to be interrogated, more often than not the thumb screws were the first resort. You’re probably familiar with this torture device—it’s basically a vise designed to clamp down around a prisoner’s thumbs or fingers. As the screw was tightened, it slowly crushed the fingers between two iron bars.

In the Castle of the Counts, thumb screws were tightened just enough to cause excruciating pain, then locked in place with a padlock. Prisoners could be left for days in this state, with no one to hear them scream but the cold stone walls.

If that still didn’t force a confession, the executioner (who was often in charge of interrogation, too) would simply shatter their fingertips with a hammer.

9Spike Collars

Sort of like a more focused iron maiden, the spike collar took torture to heinous new levels. The Castle of the Counts even had a room devoted specifically to enacting the procedure. If you click that link, you can see the crucifix-shaped window at the far end of the room. That was where a priest stood to deliver last rites if the interrogation took a turn for the fatal, which it often did.

So what was it? Essentially, it was an iron collar with needle-like spikes pointing inward. It was placed around a prisoner’s neck while he was standing in the center of a room. The collar was then fastened with ropes to the four walls. If the prisoner moved so much as an inch in either direction, the spikes would impale them through the throat. It looked something like this. Most people didn’t make it past three hours.

8The Limb Cleaver

Granted, this was more often used as a one-time punishment than as a prolonged torture device, but that flesh-hungry blade in the photo above was built for one morbidly specific purpose—chopping off limbs. In the display, this photo was also featured. At the bottom of the illustration is a pile of severed hands and feet, which may or may not have been an exaggerated depiction of the frequency with which the punishment was carried out.

In medieval Ghent, this was considered corporal punishment, similar to spanking a child who didn’t do his homework. It was done to thieves and other minor offenders. The last executioner in Ghent was a man named Jean Guillaume Hannoff. When he died in 1866, his son donated his tools to the city. Among them was the above cleaver as well as his prized hangman’s noose.

7Branding

Branding is one of the older methods of both torture and identification. From animals to human slaves, branding has been around for millennia, and it’s still used today in some livestock industries. The good people at the Castle of the Counts were never ones to reinvent the wheel, but they certainly didn’t stop any wheels from turning.

Branding at the Castle was done as a permanent sentencing. If the judge decided that a prisoner wasn’t to be killed or set free immediately, the sentence usually fell to one of three different types of brands: A “T” brand, for travaux, meant temporary forced labor. A “TP,” for travaux perpetuels, meant lifelong forced labor. And a “TPF” brand, for travaux perpetuels faussaire, meant lifelong forced labor for forgery, which was apparently a pretty serious crime to have its own category.

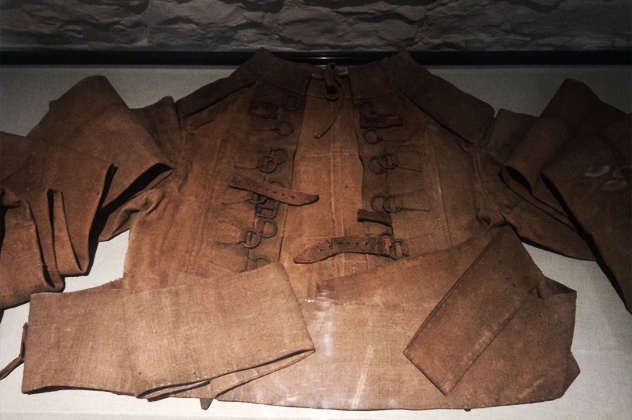

6Straitjacket Contortion

This isn’t the same straitjacket we know and love today, not by a long shot. Made out of leather, Ghent’s “straitjackets” were designed to be as uncomfortable as possible. They didn’t just keep a prisoner contained, they functioned as a complete torture system in and of themselves. The jackets had carefully designed straps on the arms that were meant to connect with buckles on different parts of the jacket. When the jacket was all buckled up, it distorted the prisoner’s body into almost unrecognizable shapes. Longer jackets could also strap onto the legs.

Prisoners weren’t usually kept in these for very long—a few days at the most—but the way the jacket twisted their limbs and spines often had lasting effects.

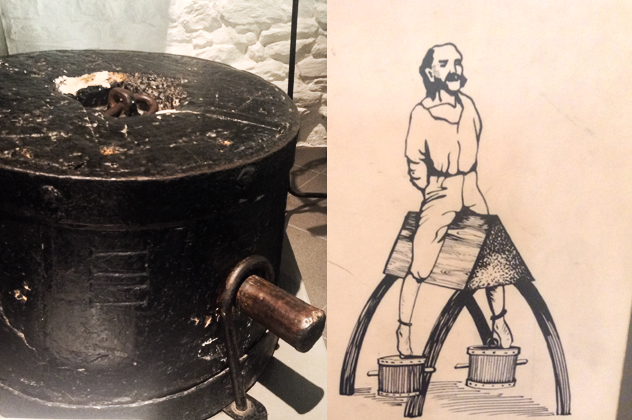

5The Mule

Sometimes called a “Spanish donkey,” this torture device is made just like a carpenter’s sawhorse, except that the top of the horizontal board rises to a sharp peak. Prisoners were made to straddle the mule while heavy weights were tied to their feet. One of the actual weights can be seen on the left side in the above photo.

The pain was, by all accounts, excruciating beyond description since the person’s entire weight was forced to a point right on their genitals. And the more serious the crime, the heavier the weights were. Supposedly, a similar device was also used by Union soldiers on Confederate prisoners during the American Civil War. Many of the victims were permanently crippled afterward.

4Mask Of Infamy

Sometimes, punishment doesn’t have to be inflicted in a lonesome dungeon. Sometimes, the public can be just as thorough in exacting swift justice. That was the idea behind masks of infamy—the mask itself, although very uncomfortable, didn’t cause any pain. Instead, prisoners were chained into the ridiculous iron masks and tied to a post in a public square where the townspeople could hurl stones and insults at them.

Masks of infamy were designed to look as silly as possible to further humiliate the wearer. And although the punishment was relatively benign, the iron could still reach roasting temperatures in the open sun on a hot day. There were likely hundreds of variations on the masks all across Europe, but in general, it’s believed that the masks with big, goofy ears (like the one above) were used for “silly” people, while masks with pig snouts were used for people who had committed a dirty crime, although there’s no indication of what exactly constituted a “dirty” crime.

3Textile Mills

From the Middle Ages until the 19th century, Ghent was a powerhouse in the Northern European textile industry. For about 500 years, it was the second largest city in Europe, right behind Paris. These days, it only has a population of about 250,000, and that’s thanks in a large part to the near collapse of its textile reign. But in its heyday, it had a comparatively large number of prisoners, and all those prisoners meant tons of free labor in its booming textile mills.

Textile mills, especially the water-powered mills operating in Ghent at the time, were incredibly dangerous. Working a mill wasn’t always a death sentence, but people often got crushed by the machinery or knocked out by the leather straps that powered the wheels. Prisoners were the obvious choice because, well, they were disposable.

One of the practices during the time was to stamp outbound cloth with a seal indicating the destination and the name of the company that had manufactured it. And if you ever come across a piece of cloth with one of the above seals on it, you’ll know it was made by prisoners at the Castle of the Counts.

2The Wheel

The wheel saw plenty of use throughout Europe during the Middle Ages, and it was a favored torture device at the Castle of the Counts. It worked in one of two ways—sometimes, the prisoner would be strapped to the wheel and slowly turned over a fire. The few moments of relief at the top of the turn gave the prisoner a chance to confess his crimes before the wheel brought him back over the scorching flames.

In the Castle, however, the preferred method was to hang the prisoner over the wheel after it had been wrapped with a strip of iron spikes. The wheel was spun so that the spikes scraped across the prisoner’s back, and if they needed to increase the pain, the torturers just had to lower the prisoner a fraction of an inch so that the spikes dug deeper into his (or her) back.

1Pressure Belts

The idea of extended prison sentences didn’t really come about until the 18th century. Before that, prisoners were held for a couple days, possibly tortured to induce a confession, and then taken before a judge for sentencing.

Pressure belts were one of the ways guards kept prisoners in check during the long hours before their trials. The belts had an iron collar that went around the neck, and chains ran from that to a wide iron belt that circled the waist. Wrist shackles were welded to the belt, and the belt itself could be cinched as tight as the guards saw fit. They were often tightened to the point of constricting the prisoner’s breathing. And since the wrist shackles were attached to the belt, tightening it forced the wrists to bend in painfully, turning it into a twisted crossover between a straitjacket and an iron corset.