Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Who's Behind Listverse?

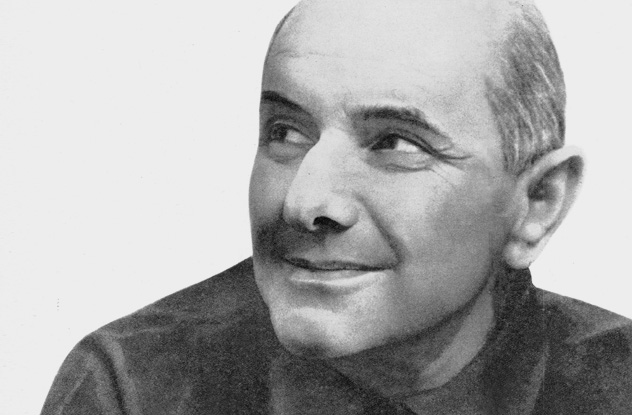

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

10 Amazing Ways People Survived The Holocaust

The Holocaust showed the horrors humans can inflict on one another. Yet the resilience displayed by those who lived through the Nazis’ brutal reign shows the strength of the human spirit. Those who escaped the Holocaust did so through cunning, daring, and the sheer unwillingness to give in to the evil around them.

10Kazimierz Piechowski

Around 1.1 million people were killed in the Auschwitz concentration camps between 1940 and 1945. Though the Nazis were murdering hundreds of people each hour, only 144 were able to escape during the camp’s five years of operation. Among them was Kazimierz Piechowski, whose breakout with three other men reads like a Hollywood drama.

Piechowski had already tried to flee from his native Poland when the Nazis arrived in 1939. The 19-year-old was caught on the Hungarian border on his way to join resistance forces. Eight months later, he was one of the earliest people shipped to Auschwitz, on the second-ever transport.

Piechowski was forced to build parts of the camp. He was also among the workers forced to move the bodies of men, women, and children shot by the SS. The prisoners were forced to work for up to 15 hours each day. Some of the prisoners were given work that granted them access to the list of planned executions. One of Piechowski’s friends, Eugeniusz Bendera, learned that he was scheduled to be shot. Bendera told Piechowski he could organize a car to escape, but a car wasn’t enough.

They had access to the storerooms, where everything from uniforms to ammunition was kept. One morning, Piechowski loosened a bolt on a trapdoor into the storerooms’ coal cellars. It was June 20, 1942, a Saturday—there were fewer Germans around on the weekend. The four plotters gathered containers of kitchen waste and told a guard that they were tasked with taking the waste away. The guard waved them out of the main camp.

The four men stole four SS uniforms. Bendera used a copied key to get into the camp’s garage and stole the fastest car in Auschwitz, which happened to belong to the camp’s commander. They drove for the main gate but didn’t know if they would need a pass to get out. As they approached, the gate remained closed. It fell on Piechowski, in the most senior officer’s uniform, to do one of the most fateful impersonations in history. In his best German, he yelled at the guard to open up, threatening retribution otherwise. The scared guard obeyed.

After two hours driving on back roads through the forest, the four men abandoned their car and set out on foot. Piechowski and Bendera joined the Polish Home Army to fight the Nazis. According to Piechowski, their daring breakout led to one of the most iconic images of the Holocaust—numbered tattoos so that inmates could be permanently identified. According to Piechowski, “No other camp used numbering—it was our escape that led to it.”

9The Stermer Family

In 1962, Frenchman Michel Siffre set a world record for time spent living underground. Yet Siffre’s 205 days had already been beaten by more than a dozen women and children. Starting in 1943, 38 Jews hid beneath the wheat fields of Western Ukraine. They were there for 344 days, but the story remained untold until 1993, when American caver Chris Nicola uncovered it.

Nicola was exploring Priest’s Grotto, the world’s 10th-longest cave at 124 kilometers (77 mi) long. The humidity is 90 percent there, and the temperature hovers around 10 degrees Celsius (50 °F). This was supposed to be a largely untouched spot, but Nicola noticed shoes, buttons, and other signs that people had lived there. Locals said that the items had been there for decades.

Nicola investigated further and encountered the Stermer family, who revealed that they and several other Jewish families had taken refuge in the cave during World War II. They’d been fortunate to find an underground freshwater lake, but food was more difficult. The men of the group had to go above ground to bargain for grain or steal vegetables. Dough and roots were almost their entire diet. They set up a kitchen underground and even a millstone for grinding flour. The hideaways suffered from scurvy and lost up to a third of their bodyweight. Miraculously, no one got seriously ill.

Gathering firewood was most dangerous. The men had to chop down trees in the dark, but it was noisy. One day after getting grain, some of the Jews were followed back to the cave by Ukrainian police. They were saved by a sack of food lodged in the cave entrance. The authorities believed the Jews were armed and had multiple entrances, so they just waited. No one left the cave for six weeks, and the Nazi collaborators eventually gave up.

When the Germans were forced away by the Red Army, one of the group’s surface helpers dropped a note in a bottle into the cave entrance. “It was unbelievable to think that I could go outside, go around in daylight, and nobody was going to kill me,” said Shulim Stermer, who was in his twenties at the time. All of the 38 people that entered the cave came out alive.

8Leo Bretholz

Leo Bretholz was 17 when he was forced to flee from his home in Austria. It was 1938, and Jewish men were being arrested daily by the Nazis. Bretholz’s mother bought him a train ticket to Trier, near Germany’s border with Luxembourg. The young runaway forded the Sauer River to escape Germany and crossed to Belgium. But that was only the start of seven years of extreme running, hiding, and a lot of escaping.

Bretholz slept in ditches, found refuge in monasteries, and hid with his people in Jewish ghettos. He was arrested in 1940 and escaped by digging under a fence. He was captured by the Nazis a further six times, but he made his most spectacular getaway in 1942. On November 5, he was crammed into a cattle car on a Nazi train headed for Auschwitz. Along with another man, he spent the day prying at the bars of his cell. Then, when darkness fell, he leaped from the moving train. He needed to wait for the train to slow on a bend and avoid the searchlights operated by Nazi guards at those points in the track.

In the late 1940s, Bretholz joined a Jewish resistance group fighting the Nazis, forging IDs, and hunting down German troops. He moved to the US after the war and became a key witness in lawsuits aiming to get compensation from the French rail company that had been complicit in transporting Jews to their deaths. He wrote a book with a title inspired by his great escape, Leap Into Darkness.

7The Sobibor Breakout

One-third of the six million Jews killed in the Holocaust died in three camps in east Poland between March 1942 and October 1943. At one of these, Sobibor, victims were shipped in on a train and were told they were being showered to prevent disease. The prisoners would often celebrate this news after so many hours crammed into a rail car. Then they were led into a gas chamber.

The Nazis kept 600 “work Jews” alive, but they would continually kill and replace these men to prevent a chance at rebellion. By the summer of 1943, the Soviets were nearing the camps, and Himmler wanted to erase all trace of them. The Jewish workers realized that their deaths were inevitable when trains stopped arriving. Some managed to make a run for it, but 10 Jews were executed for each escapee. A minefield was laid around the camp. A mass outbreak was the only option left.

The Jews made a plan to break out in October when the camp’s toughest SS officer was on leave. At 4:00 PM on October 14, the schemers lured 11 guards into individual traps. The camp’s phone lines were cut. But as the daily roll of the prisoners was being called, a guard found one of his dead colleagues and raised the alarm. One of the leaders of the rebellion leaped on a table and told everyone to run, telling the crowd to “let the world know what has happened here.”

During the escape, 250 people were killed by the Nazis. Among the 58 that survived was 16-year-old Thomas Blatt, who was shot and left for dead by a farmer during his escape. He moved to California and has published works and given interviews about his experiences. He testified in 2009 against one of the camp guards, Jan Demjanjuk, and also became one of the few survivors to privately interview someone behind the atrocities.

6The Arshanskaya Sisters

In the winter of 1941, Nazi troops invaded the Ukrainian city of Kharkov. Many Jews died, some hung from lampposts. The soldiers forced thousands to march 20 kilometers (12 mi) out of the city. The Arshanskaya sisters, 14-year-old Zhanna and 12-year-old Frina, were among 13,000 people crammed into an old tractor factory designed to house 1,800.

The girls’ father bribed a Ukrainian guard with a golden pocket watch to secure the release of one of his daughters. He told Zhanna to run, since the older girl had more chance of surviving. Zhanna never saw her father again but was reunited with Frina within a few days. The younger girl never revealed how she was able to get away. The sisters found their way to an orphanage, where the staff created fake identities for them.

Zhanna had been playing the piano since she was five. When a local piano tuner heard her play, he offered the two girls a place with a musical troupe that entertained the occupying Nazi forces. The girls began hiding in the spotlight, providing entertainment for the people who had tried to condemn them to death. “We were a precious commodity for the Germans,” Zhanna later said.

Their value to the Nazis saved their lives. They were ratted out as Jews, but the soldiers declared that there was no proof and kept the girls around. By the end of the war, the musical troupe was taken to the Nazi heartland of Berlin.

When the liberators arrived in 1945, the girls were taken to a camp run by American officer Larry Dawson. His brother was an accomplished musician, and the Holocaust was no barrier to love stories. Zhanna married David Dawson after moving to the United States. She has one memento from her life before the Nazis arrived: a sheet of her favorite music. Zhanna grabbed it and kept it with her when her family was forced from their home. It is kept in a safety deposit box, as a treasure for future generations of her family.

5Stanislaw Jerzy Lec

The Polish poet Stanislaw Jerzy Lec was a journalist working in Poland when the Nazis invaded. He tried to flee to Romania but was caught and wound up at the Ternopil concentration camp, where he was led into the woods, given a shovel, and forced to dig his final resting place.

The guards who had taken Lec became bored and hungry. One of them was forced to stand with the prisoner while the rest left to get supper. Lec waited until the right moment and killed his captor with a blow to the neck. He later captured the moment with the following poem:

He who had dug his own grave

looks attentively

at the gravedigger’s work,

but not pedantically:

for this one

digs a grave

not for himself

Donning the dead man’s SS uniform, Lec made his way to Warsaw, where he met members of the Polish resistance. There, he put his literary skills to use publishing underground newspapers. He was also fluent in German and wrote leaflets for the resistance. He ended the war as a major in the Polish army and fought in battles pushing back against the Nazis.

4Yoram Friedman

Yoram Friedman was five years old when Nazi troops arrived in his Polish hometown of Blonie. It was 1939, and within three years, Friedman and his family were forced into the infamous Warsaw Ghetto. About three-quarters of the 400,000 Jews who lived in the Ghetto were killed by the Nazis. Yet Friedman was smuggled out, leaving him to try to keep himself alive in Nazi-occupied Poland at the age of eight.

He initially joined a group of Jewish orphans who survived by raiding farms, but that didn’t last. Alone again, he knocked on the doors of Polish farmers to beg for help. After being rejected and beaten, he was taken in by a Catholic woman named Magda. She taught Friedman Catholic prayers, renamed him, and warned him never to urinate around Poles because it would reveal that he was circumcised. Local villagers nonetheless suspected that Magda was housing a Jew and reported her to the SS. Her home was burned to the ground, but Friedman was able to get away.

He lived in the wild, tying himself to branches high in trees to sleep. He ate wild berries and whatever animals he could catch. A seemingly miraculous chance meeting with his father lasted only moments, when the elder Friedman was caught by Nazis and shot in a potato field.

Friedman resumed his Catholic identity, going by the name of Jurek, and he found work on a farm. His arm got caught in a wheat grinder one day, and local doctors refused to treat him when they realized he was Jewish, so he lost his right arm entirely. Yet Friedman overcame even this, finding a place in an orphanage when the Soviets arrived in Poland.

Three years later, he was found by a Jewish agency and arrived in Israel. Despite being illiterate at that point, teenage Friedman went on to earn a master’s degree in math and spent his life as a teacher. In 2013 a film, Run Boy Run, was produced based on his story.

3Rolf Joseph

The Joseph brothers, Rolph and Alfred, had everything against them. They were teenagers in a Jewish family when Hitler came to power, and they lived in Berlin. Their father had fought for Germany during World War I, so they clung to hope that the family would be okay in his home city. But by the 1940s, the boys were left on their own, their parents arrested and shipped away by the Nazi regime.

No one who knew the brothers could shelter them together. So they lived separately but met every Wednesday at 11:00 AM, until one morning in 1942. Rolf was accosted by a German soldier and was taken away for interrogation. He was locked in a cell by the Gestapo and whipped for hours to reveal his hiding place and the whereabouts of his brother. Rolf held out, and he was on a train to Auschwitz the next day.

Rolf grabbed a pair of pliers from a toolbox in the van that transported him to the train station. He used them to work himself out of his handcuffs. Rolf and his fellow prisoners were able to break a plank away from the side of their cattle car and jump from the train.

Yet Rolf’s freedom was short-lived. On the way to Berlin, he was betrayed to the Gestapo and arrested again. He was beaten so severely that he developed epilepsy. But Rolf was unbreakable, and he hatched a plan. When he was left alone, he scratched himself and convinced his guards that he was suffering from scarlet fever. The Germans, fearful of catching something, moved Rolf to a hospital. A guard stood outside Rolf’s third-floor room, so he jumped out of the window.

Despite breaking part of his spine, Rolf crawled through the city to his old hiding place. His brother was there, and the old woman who had taken them in moved them to some land she owned in Berlin’s outskirts. The brothers were liberated by the Soviets in 1945, and Rolf went on to become an engineer.

2The Chiger Family

One of the largest Jewish ghettos created by the Nazis was in Lwow, Poland. When the Nazis invaded, 200,000 Jews lived in the city, half of them refugees from Germany. In June 1943, the Germans liquidated the ghetto, killing thousands of Jews in the process. Weeks before, a small group led by a man named Ignacy Chiger had dug their way through the floor of their building, using only cutlery. They wanted to find a place to hide, but before they could find a new home, they were found by Polish sewer workers. Among them was Leopold Socha, chief supervisor of the city’s entire sewage system.

Socha was sympathetic to their plight, but surviving in the sewers was hellish. The city’s sewage system drained into the fast-moving River Poltwa. Early in their 14-month stay underground, the children’s uncle slipped into the river and was washed away to his death. The sewer was shared with the city’s rats, who tried to steal the group’s food. Five weeks into the stay, the group was discovered by unfriendly workers and had to run into the darkness. They were lucky enough to bump into the workers who knew them, who guided them deeper to a new hiding place.

When it rained heavily, their area of the sewer would flood and leave only a few inches of space. The parents held their children with faces pressed against the ceiling to breathe. Krystyna Chiger developed a phobia of rain. “I would sit and listen to hear if it was raining, and panic as soon as I heard rain drops,” she said later. Both her children developed measles, but both miraculously survived. One of the women was pregnant when they entered the sewers. When their baby was born, its cries threatened to give away the group’s existence. Giving testimony in 1947, Krystyna described how “they covered this child with a washbasin. It suffocated and was thrown into the Poltwa.”

Out of 21 who entered the sewers originally, only 10 survived. Krystyna was overjoyed when the Soviets arrived and she could leave the sewers. Brother Pawelek, too young to remember much of life out of the sewers, was scared of the light and people. He cried to go back underground.

1Michael Kutz

Michael Kutz was 10 when the Nazis arrived in Nieswiez, Belarus in June 1941. At first, they forced the town’s 4,500 Jews to work. Kutz cleaned streets and toilets by day. At night he sneaked out and traded textiles for food, to feed him and his mother. On October 30, the Nazis made every Jew gather in the town square. Those who could work were placed in one group to be kept alive. The rest, including the children, were to be shot.

Nazi soldiers marched the condemned 5 kilometers (3 mi) into the countryside. Many were shot on the way. The Jews were forced to undress completely and lined up beside a mass grave. Yet the Nazis didn’t shoot all of their captives before burying them. They ordered those remaining to jump into the pit to be buried alive.

Kutz hesitated, and an officer smashed his head with a rifle. The young boy fell in and was slowly buried beneath the dead and the dying. He later recalled. “I tried as a kid to throw away dead bodies, dead parts of bodies and everything, and to be able to breathe, and then it was quiet.”

Kutz crawled up through the pit of bodies and saw that no one was there. He ran, still completely naked. He didn’t stop until he reached a convent, where the nuns gave him clothes and some food. They were too fearful to harbor a Jewish runaway, though, and Kutz was on his own.

He eventually met up with some Russian resistance fighters, who were impressed by Kutz’s survival of the pits. They spent the next three years living in the forest, fighting the invading force. Only 12 other Jews from his town survived.

Kutz wrote an autobiography, If, By Miracle. The title was inspired by the last words from his mother, whispered to him during their march to the death pit. “If, by miracle, you survive, you must bear witness,” she told him. Through the hunger, rough sleeping, and difficulty of fighting, he says his mother’s final words inspired him to go on.