Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Flops That Found Their Way to Cult Classic Status

History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

10 Sultry, Scandalous And Riotous Affairs From Early Theater

There’s always been something a little bit different about the people in the theater. Whether they live onstage or backstage, there’s something a little more exotic about them. They’re a little different, spending much of their time wrapped in imaginary worlds with imaginary characters. In the end, though, most of them provide a pretty unblinking look at the real world, and sometimes the real world just can’t handle that.

10 Charlotte Charke

When writing her memoirs, Charlotte Charke (wearing pink in the picture above) says, “I am certain, there is no one in the world more fit than myself to be laughed at.” What was certain was that 18th-century London had no idea what to make of Charke and her alter ego, Charles Brown. While it definitely wasn’t strange to see cross-dressing on the stage, Charke went a few steps further in creating Charles Brown as an extension of her everyday, offstage self. As Charles, she dressed like a man and stepped into roles and attitudes traditionally reserved for men.

A playwright and actress, Charke was known for wearing pants, riding horses during the day, and poking fun at those who thought she was scandalous in her writing. In the theater at night, she was fond of what were called “breeches roles”; she was well known for her portrayals of male characters, bringing them to the stage in a fashion that wasn’t a woman playing a man, but simply a male character. Her written works have the same kind of incredible duality, and it left her audience not quite sure what she was.

Popularly, she was called a lesbian, whore, deviant, and a prostitute. When she released her memoir, it was labeled a “scandal memoir,” full of the sorts of stories that just had no place in 18th-century life. She was incredibly outspoken and financially independent; she spoke of female friendships and acquaintances and counted among her friends the girls living and working the streets in Covent Garden. While her sister, Catherine, pointed to her lifestyle and her clothing choices as being responsible for breaking up their family, Charke herself reveled in who she was and, strangely, there was nothing truly scandalous about her—only her ability to touch both her femininity and masculinity and wear pants.

9 The Great Lafayette

Sigmund Neuberger, the Great Lafayette, was born in Germany in 1872. By the early 1900s, he had taken London by storm with his magician act and was soon making an annual salary of what today would be about $2.75 million. His relationship with his dog, Beauty (a pit bull gifted to him from Harry Houdini), was legendary, but his treatment of his staff and assistants was the stuff of cringe-worthy hatemongering.

It was said that he insisted that those who worked with—and beneath—him would be required to salute him in greeting. He requested complete openness about all their affairs, to the point of divulging their financial records should he want to see them. Surrounded by that kind of loyalty, it wasn’t all that surprising that when Beauty died, he insisted that she be buried as a human, on consecrated church ground. The idea was pretty scandalous, and the only way the church would do it was if he was buried beside her.

It wasn’t long before he was. Only about a week after Beauty’s death, one of Neuberger’s shows went horribly, horribly wrong. The stage caught fire, and the audience was only saved by a quick-thinking conductor who, rather than shouting “Fire!” and causing a panic in the crowd that thought it was all part of the show, simply started playing the exit music, causing people to file out. The Great Lafayette, though, made a pretty valiant, but unsuccessful, attempt to save the horse that was part of his show. He wasn’t done with the mystery yet, either, as when his body was recovered, his lawyer had some pretty intriguing questions about what had happened to the rings that he always wore.

The answer was bizarrely, disturbingly simple. The body they were originally preparing for burial wasn’t Lafayette at all, but one of his doubles. The correct body was finally recovered, and Neuberger was buried beside Beauty.

8 Isle of Dogs Scandal

It’s a good scandal that ends with a massive amount of arrests and the seizure—and destruction—of private property. Especially if even today, we’re not even sure exactly it was all about.

In 1597, a play called Isle of the Dogs was premiered at the Swan Theatre in London. Written by Ben Jonson and Thomas Nash, the play has since been lost, presumably destroyed in the fallout afterward. It’s thought that the content of the play had something to do with portraying Queen Elizabeth in something of a negative light, and it’s generally believed that her court and courtiers were the “dogs” mentioned in the title of the play.

After the premiere of the play, the Privy Council issued a handful of proclamations; what we know about the ensuing events is largely pieced together from these documents. And while some of those documents include things like orders for playhouses to not stage Isle of the Dogs ever again, another includes instructions to a man named Richard Topcliffe, notable as the royalty’s heretic hunter and one of the court’s chief torturers. Topcliffe was ordered to, shall we say, speak with the actors that had performed the play and then been arrested. There were arrest warrants issued for Jonson and Nash, along with authorization to seize copies of the play and other documents from the playwrights.

Some of the documents give the barest of clues as to what the play was about, and suggest that there were some sort of references in it to some rather improper relationships between the Queen and other royals. Other noble families are named as being quite offended by the whole thing, and as if the content wasn’t bad enough, the rather explosive popularity and reaction from the crowd was deemed nothing short of humiliating.

In the end, the Swan was shut down completely, Jonson would serve a jail term, and Nash would end up fleeing the country to avoid the same fate. His home was searched, and all his personal papers were seized and destroyed. They certainly did a good job at shutting the play down, as there’s no trace of the slightest bit of dialogue or narrative from the play still in existence.

7 Adah Menken

There’s pretty much nothing about Adah Menken that’s not the stuff of legendary scandal.

Born in Louisiana in 1835, she was known as “The Naked Lady” for her burlesque shows. This was a time when burlesque and, indeed, naked ladies were reserved for a very specific sort of crowd and a very specific sort of place, and she brought it to the main stage. In 1863, she was seen on stage by Mark Twain, still in his journalism days, who wrote about her and the uproar her performances brought in San Francisco. (In fact, a signed copy of his article about her is one of the first documents we have where he used the name “Mark Twain.”) When she hit the stage, men threw bags of gold dust on the stage, and women collected her photos and followed her stories.

Her work on the stage was nothing short of sensational, especially her portrayal of Mazeppa, when her character was stripped naked (she was wearing a flesh-colored bodysuit) and tied to a horse that charged up an onstage mountain four stories tall. Others attempted the same stunt, and at least one died doing it.

She was just as scandalous off the stage as she was on it. She kept her early years secret, and it only came out in the 1930s that she was the illegitimate daughter of a French-Creole woman, with the true identity of her father never established beyond a likely candidate. She married first at age 21, a union that ended when she refused to stop smoking in public. She married a boxer, had a child with him, and then divorced him. Menken ran into a bit of trouble when it turned out that she hadn’t exactly divorced her first husband, claiming that she had just assumed he had taken care of it. The child tragically died, and Menken forced herself to keep going. She conquered San Francisco, London, and Paris. She also rubbed elbows with the Dumases and wooed Charles Dickens. Menken died at 33 years old.

6 Richard II And A Failed Rebellion

Theater has been around for centuries, but it was only at the end of Queen Elizabeth’s reign that people in England were really starting to discover just what a powerful tool it could be. It was then that most of the big theaters started popping up and that it became an organized thing.

One of the most popular of the playwrights was, of course, Shakespeare, and some of his works were pretty dangerous at the time, especially considering the religious and political climate. In 1601, Shakespeare and his troupe were approached by the Earl of Essex, who asked them to stage a production of Richard II. (It’s the first one in the series that tells the story of the rise of the Lancaster house and that features a wasteful Richard, more concerned with his own luxury than the livelihood of his people.)

There were enough similarities between Richard and Elizabeth to make the play a pretty uncomfortable one. Both had an incredibly close group of advisers, and neither had a biological heir to the throne. In 1601, they were only a couple years away from the aging Queen’s death, and the play, which told the story of a monarch leaving the throne without actually being shown to resign, would have touched a few nerves at the time.

That’s what the Earl of Essex was counting on. The night that he wanted the play staged was the night before his own planned rebellion against the Queen. The play was staged and, the next day, the Earl and 300 of his men attempted to take the throne by force.

They failed, and the Earl was taken prisoner. Unlike the fallout that surrounded the Isle of the Dogs, Elizabeth took the opportunity to embrace Shakespeare’s play—sort of. She asked the same group of actors to perform it for her, on the night before she had the Earl beheaded.

5 The Golden Rump

In the 1730s, Henry Fielding was one of the most popular names on the English stage. (He’s also the one that wrote The Female Husband, or the Surprising History of Mrs. Mary, alias Mr. George Hamilton, which we’ve covered before.)

While much of his early work was lighthearted (and, in the grand scheme of things, pretty harmless), as he became more and more popular, he began writing things that were more and more political. By 1737, he was releasing works that depicted completely irrational politicians and works that were very straightforward in the mocking tone they took toward the government. Because governments tend to be proactive about that sort of thing, it was the same year that the Licensing Act was issued, which changed the face of theater for decades. Only two theaters were left open, Covent Garden and Drury Lane, and the act outlawed political satire as well as anything that could be deemed as a less-than-stellar commentary toward the monarchy.

The work that broke the camel’s back, The Golden Rump, has sadly been lost to the history of repressed works. There’s been debate over whether or not it even existed, but there’s a handful of references to the work being produced in the 1735–36 theater season. Although it’s Fielding’s name that is most often associated with it, it’s also been suggested that the play was the work of the government itself, to give them an excuse to issue the Licensing Act. The only thing we do know about it is that it was called obscene, and one of the scenes was apparently suggestive to the idea that a king liked to receive enemas from his queen.

4 Louisa Fairbrother And The Duke Of Cambridge

Louisa Fairbrother was a ninth child, whose father had tried to dissuade her from becoming an actress. Actresses had less-than-stellar reputations in the mid-19th century, and according to popular belief, many were only a few steps away from complete harlots. She took to the stage, though, performing across London, at both Covent Garden and Drury Lane.

It was, perhaps, a good thing that she didn’t listen to her father, either, as the stage is where she was when she caught the eye of Prince George, Duke of Cambridge. She was best known for playing Abdullah—complete with facial hair—in a burlesque version of Open Sesame, an interpretation of The Forty Thieves. Once George saw her and became completely enamored by her, he was a frequent sight outside of the Lyceum’s stage door. While it wasn’t unheard of for royalty to keep mistresses who were working on the stage, marrying one was quite another matter. Nevertheless, George did, while she was pregnant with their third baby. Not surprisingly, it was something that was kept well under wraps, especially because he hadn’t gotten permission to marry from the Queen, as tradition and law dictated for the royal family.

The details of the marriage are pretty well hidden, even from the prince’s royal biographer. It’s thought, based on letters, that they were married on January 8, 1847; the scandalous wedding was a secret, though, and there are several contradictory letters and rumors of falsified records. Tracking down the marriage records afforded the biographer with a rather odd find: It had been 1847, but the signature is George Cambridge. It’s generally suggested that Prince George deliberately wrote his name wrong to hide the marriage. The whole thing is more than a little mysterious.

3 The Old Price Riots

In 1808, the Covent Garden Theatre was destroyed in a fire. After rebuilding next year, the theater’s owner, John Philip Kemble, needed to recover the immense amount of money that he’d spent, so he raised ticket prices.

He made the announcement at the beginning of the first show in the newly rebuilt theater. It was Macbeth, with Kemble playing the titular role. Oddly enough, he apparently didn’t think much about the raised prices. They led to an immense heckling and caused such an angry uproar in the crowd that the actors ended up having to mime the entire play, because no one could hear them anyway.

The result was 67 nights of rioting, over a price jump from six shillings to seven for the box seats and from three shillings, six pence to four shillings for non-gallery seats. Everyone, from the working class to the professional patrons, took up the cry of “Old Prices!” and demanded a return to the old ways.

It wasn’t just a matter of theater owners charging more, either. Kemble was accused of taking away their national identity, of preventing the citizens from seeing the plays of the greatest literary giants of their country, and even of taking away actors’ chances at celebrity. He was called “King John,” the subject of songs and angry posters, and the mob staged their own plays—nightly, in the form of riotous acts that cast their King John right in the middle of it all.

When Kemble finally backed down, they called it the signing of the Magna Carta.

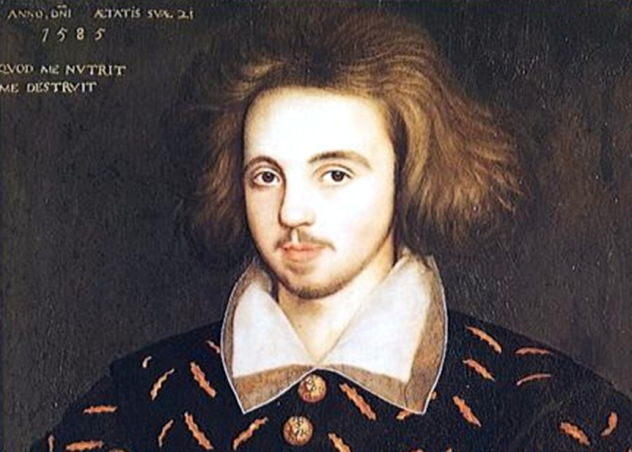

2 Christopher Marlowe

Today, Shakespeare is the big name in Elizabethan poetry, and Christopher Marlowe is something of a relatively minor footnote, usually mentioned in the same sentence as Shakespeare as a likely candidate for who really wrote all those plays.

It’s a shame, because Marlowe’s life was epic; it was the life of a scandalous social dissident who died in a mysteriously unexplained bar fight when he was 29. He managed to pack a lot of living into those 29 years, giving any modern tabloid darling a run for their money.

He was a contemporary of Shakespeare, and he was much, much more popular (though Shakespeare was only starting his career), with Doctor Faustus and Tamborlaine both revolutionary works for which the time was just right. The son of a shoemaker, he ended up working his way through several degrees in Cambridge. However, once he was out, he was still from a poor family, and that meant limited opportunities. So, he turned to one of the places that he could put his education and intellect to work, the theater, and he didn’t pull any punches when it came to calling out the unfairness that he saw in the world around him.

While he was at Cambridge, it’s thought that he was recruited as a spy, although at a time when religion was deadly, it’s not clear exactly where the lines were drawn. A couple of years after Cambridge, he spent some time in Newgate Prison, after a bar fight that left one man dead. Meeting a man there who had an in with a counterfeiting ring, he became a counterfeiter for a while before ending up in jail again, this time in the Netherlands. Just how easily he got off has been seen as evidence that he either knew something that was extraordinarily important to the Crown, or he was something extraordinarily important . . . perhaps both.

He gave regular reports to the Privy Council and ran with groups of loan sharks and spies. At a time when religion was sacred, he went on record as saying that Jesus was a bastard and Mary was a liar. He died a rather premature, violent death at the home of a woman named Eleanor Bull, who happened to be related to the governess of Queen Elizabeth. The official story is that it was a fight over the bill, but with witnesses that didn’t intervene and a queen that pardoned the killer, the whole thing was incredibly, incredibly suspicious.

1 The Catholic Church’s Excommunication Of Actors

As we’ve said, the people of the theater have always been seen as a little different, and at one time, they were downright sinful. So sinful, in fact, that to be an actor or an actress was to be automatically excommunicated from the Catholic Church.

In the 19th century, Church doctrine made it very, very clear what they thought of acting. According to Cardinal Manning, acting was “the prostitution of a body purified by baptism.” As such, they were excommunicated, refused sacraments, not allowed to be buried in consecrated ground, and forbidden from interacting with anything holy. They weren’t allowed to get married in a church, and, more than that, they weren’t allowed to speak on anyone’s behalf in a court case, give evidence in court, or be hired into any sort of public office.

The laws dated back to well before the 19th century. In 1789, a petition was put before the National Assembly in France to overturn some of those laws and restore the right to hold public office to several groups of people that had been previously barred from it: Jews, Protestants, and actors. Even though the laws were repealed and, in theory, equal rights were granted, it didn’t happen in practice, and many funeral processions of actors still found church doors quite literally closed, locked, and barred.

The theater then, much like today, was largely a place for the young, and that meant when it came time to retire, many found themselves unable to shake the stigma of their theater connections. Noah Ludlow, a theater manager in the 1820s, recorded some of the scandals caused when ex-actors left the stage and tried to make a go of it in the everyday, ordinary, unimaginative world. One he speaks of, Charles Parsons, attempted to become a Methodist minister; when his congregation found out that he had been an actor, the protests over his position forced him to resign.