Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Widespread Historical Myths and the Texts That Started Them

Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

Technology

Technology 10 Unsettling Ways Big Brother Is (Likely) Spying on You

Music

Music 10 Chance Encounters That Formed Legendary Bands

Space

Space 10 Asteroids That Sneaked Closer Than Our Satellites

Sport

Sport The 10 Least Credible Superstars in Professional Sports

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 of History’s Greatest Pranks & Hoaxes

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Widespread Historical Myths and the Texts That Started Them

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

Technology

Technology 10 Unsettling Ways Big Brother Is (Likely) Spying on You

Music

Music 10 Chance Encounters That Formed Legendary Bands

Space

Space 10 Asteroids That Sneaked Closer Than Our Satellites

Sport

Sport The 10 Least Credible Superstars in Professional Sports

10 Bizarre Ways That Tiny Countries Make Money

Being a small country is tough these days. With the demand for copra and calypso not what it once was, tiny islands around the world have frequently found themselves strapped for cash. That helps to explain why some of the world’s smallest countries have been turning to increasingly creative means to meet their budget shortfalls.

10Selling Passports To Rich People

With a population of just 48,000 and a failing sugar industry, the tiny Caribbean country of Saint Kitts and Nevis was in a bad state in 2006. It turned to the one resource it had left—its passports. Teaming up with a Swiss lawyer named Christian Kalin, the country revamped an existing citizenship-by-investment program into a money-spinning sensation. For just $250,000 or a $400,000 investment in local real estate, anyone in the world could become a full-fledged citizen of Saint Kitts and Nevis, even if they had never set foot in the country and never intended to.

The program was a huge hit. Kittitian citizens got visa-free travel to 132 countries, including most of Europe, and extremely favorable tax arrangements. In 2013, Saint Kitts made $100 million from the program, representing around 13 percent of the country’s entire GDP. Soon, other small island countries were lining up to sell their passports, creating a whole cottage industry worth an astonishing $2 billion per year. When Antigua and Barbuda started selling citizenship in 2013, the profits were projected to account for a full quarter of government revenue. However, Prime Minister Gaston Browne insisted that prospective citizens had to live in Antigua for at least five days first, telling Bloomberg that otherwise it might “appear as just a vulgar sale of passports.”

Naturally, the program has caused some controversy worldwide. Canada broke its visa-waiver deal with Saint Kitts and Nevis in 2014, the same year that the US Treasury warned that wealthy Iranians might use Kittitian passports to avoid sanctions. (Saint Kitts says that Iranians have been banned from the program since 2011.) Meanwhile, the European Union had to hastily intervene after Malta tried to enter the industry, pressuring the country into raising the price and installing a yearlong residency requirement for potential citizens. However, it’s tricky for larger countries to push back too hard against the program, since they themselves usually let wealthy foreigners jump to the top of the immigration queue. For example, a US green card can generally be obtained in return for a $500,000 investment in the country.

9Selling Passports To Poor People

While some islands rake it in selling passports to the wealthy, there’s another group of people desperate to obtain citizenship, even if they never set foot in the country involved. There are currently an estimated 10 million stateless people in the world. Among them are Arabia’s Bedoons, descendants of nomadic tribes who were not given citizenship in Kuwait or the United Arab Emirates when those countries became independent. They have been consistently refused citizenship since then, officially depriving over 100,000 Bedoons of many basic rights.

In recent years, there has been increasing pressure for the Persian Gulf states to resolve the ridiculous situation. However, they have consistently been unwilling to naturalize the majority of Bedoons. In 2008, the UAE begrudgingly offered the Bedoons 8,000 citizenship papers. An estimated 80,000 Bedoons were seeking citizenship in the country at the time.

That’s when a Kuwaiti named Bashar Kiwan had a bright idea. Kiwan was a major investor in the Comoros, an island country of about 800,000 people in the Indian Ocean. The country was terribly impoverished, with most Comorians living on less than $1.25 per day, and the government was desperate for money. So Kiwan brokered a deal in which the UAE paid the Comoros $200 million in exchange for passports for 4,000 Bedoon families of up to eight people each.

The deal caused huge controversy in the islands, but the Comoros government was desperate. In 2009, the president addressed the nation:

This will put an end to our water problems, our road problems, our energy problems. It will serve to build our ports, our airports, real schools to last a hundred years. My brothers, this is one of the paths I’ve gone down to generate wealth for our country. That’s what we’re missing in this country: money. And here is money, which, by the grace of God, will in the coming days be transferred into the central bank.

Since then, neither the Comorians nor the Bedoons have been too happy with the deal. Earlier this year, the Comorian government seized Kiwan’s remaining assets in the island, saying it was obvious that he “did not transfer the whole amount that was owed to us.” Meanwhile, many Bedoons say they were pressured into taking Comorian citizenship, without which they couldn’t even renew their license plates. They were also promised that Comoros citizenship would be a step toward gaining Emirati passports. That hasn’t happened. Bedoon activists and protesters now find themselves facing “deportation home” to a country they’ve never even seen before.

8Niue Hosted Phone Sex Lines

Niue is a tiny island in the Pacific with a declining population of around 1,190, down from over 5,000 during the 1960s. For many years, agriculture, fishing, and the occasional tourist were the mainstays of the Niue economy, but that all changed in the late 1980s, when the government signed a deal to allow premium-rate phone lines to be routed through the country’s area code. Banks of phone lines were installed, allowing calls to be switched through Niue to destinations around the world.

There was just one problem. The conservative Christian islanders were soon flabbergasted to realize that most of their new business actually consisted of phone sex hotlines, which were routed through Niue for financial reasons. To make matters worse, misdialed numbers meant that the islanders themselves were frequently woken in the middle of the night by “heavy breathers” from Japan or the UK. By 1997, nearly everyone on the island had learned to be wary when answering the phone late at night.

On the other hand, the phone lines were enormously lucrative for Niue. Niue’s local telephone company allowed the phone lines to charge a hefty rate per minute, taking a large royalty in return. In the UK and Japan, phone companies would have blocked calls to lines charging such rates, but blocking international calls is much more difficult. To make things even better, Niue telephone numbers only have four digits following the country code, meaning that many callers didn’t realize they were making international calls until their bill arrived. One Japanese woman was shocked to find her son had spent $3,700 on the hotlines in just one month.

So even if a pornographic phone line was entirely based in the same country as their customers, it made sense to route the calls through Niue, pumping money into the island in the process. As it turned out, it wasn’t quite worth risking a disturbing late-night phone call. Niue’s prime minister canceled the deal in 1997.

7Tuvalu Doubled Its GDP Online

A tiny string of coral atolls in the Pacific, Tuvalu has a population of around 11,000 and is slowly being submerged due to global warming. To make matters worse, it’s one of the most isolated countries in the world, with little to base an economy on. For years, the country had to follow Niue’s lead and earn revenue by allowing international phone sex lines to be routed through its 668 area code. That brought in over $50,000 a month, increasing government revenue by 10 percent, but the Christian islanders found it morally upsetting.

Everything changed in 1999, when Tuvalu was awarded the Internet suffix “.tv” and promptly became the subject of an international bidding war. No less than five Internet companies sent representatives racing to the islands to bid for the rights to .tv, which was sure to be a hot address for media websites. The eventual deal netted Tuvalu a $30 million advance payment, literally doubling the country’s GDP that year.

By 2011, Tuvalu was receiving $1 million a year in .tv royalties, which made up a significant proportion of the country’s annual income. However, the islanders weren’t happy, insisting that they were being cheated out of another $4 million from .tv’s huge sales. Their other problems persist, with one domain registrar warning against buying a .tv address, since “the island of Tuvalu is sinking.” Still, at least it let them cancel the phone sex deal.

6Nauru Staged A West End Musical

With a population of just 9,540 people, the tiny Pacific island of Nauru is the smallest republic in the world. But in their first decades of independence, the country actually did pretty well, helped by extremely valuable phosphate exports. In fact, during the 1970s and 1980s, Nauru was perhaps the richest country per capita in the world. Nauruans bought sports cars to drive on the island’s single paved road and chartered flights for shopping trips to Fiji and Hawaii. Even the police chief had a yellow Lamborghini, although he was too fat to actually get into it.

However, that wealth came at the expense of heavy and environmentally damaging mining, and by the early 1990s, it had become clear that the phosphate deposits were going to run out sooner rather than later. So Nauru began to invest in a string of overseas business ventures, most of which failed. Particularly notable was the £2 million musical that the island staged in London’s West End.

Entitled Leonardo The Musical: A Portrait Of Love, the show told the dramatic and historically suspect tale of the romance between Leonardo da Vinci and the Mona Lisa. The whole thing was orchestrated by Duke Minks, former manager of 1960s pop sensation Unit 4 + 2, who had somehow become an adviser to the Nauruan government. After Duke played some of the songs during a meeting of the Nauruan cabinet, the government agreed to fund the musical. Nauru’s president even flew into London for the premiere, declaring, “I am really excited. I am trying to be objective, but I have my fingers crossed that this show will tour the world.”

Unfortunately, it didn’t work out that way. The London Evening Standard called the show “an extreme load of rubbish,” and it quickly proved a flop. Economic conditions on Nauru subsequently deteriorated as the phosphates ran out, and the island now makes much of its money by hosting a detention center for asylum seekers barred from entering Australia.

5The Islands Where Postage Stamps Are The Main Export

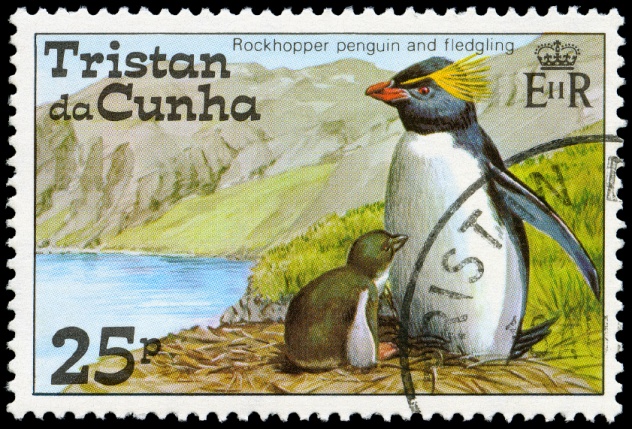

Stamp collecting became a hugely popular hobby in the 19th century, almost immediately following the actual invention of postage stamps. By the early 20th century, it was a worldwide craze, with a small but thriving industry dedicated entirely to collecting. This turned out to be great news for the tiny British territories of Saint Helena, Ascension Island, and Tristan da Cunha, conveniently located nowhere near each other in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

In the 1920s, Ascension Island became a dependency of Saint Helena and decided to celebrate by issuing a set of Saint Helena stamps that simply had “Ascension” printed at the top. To the islanders’ surprise, they were soon flooded with letters from collectors around the world who wanted to purchase sheets of the exotic new stamps. Sensing an opportunity, Ascension started printing its own stamps in 1924, which proved no less popular. These days, Ascension (whose current population is around 1,000) issues five sets of stamps every year to the delight of collectors, around 400 of whom have standing orders for every new stamp that the island produces. Ironically, the island itself is so small that mail is rare, and there is no national postal delivery service.

Naturally, Saint Helena quickly jumped on the bandwagon and also derives a good portion of its income (which totals less than £1 million) from selling its stamps and coins to collectors. But the king of the stamp islands is surely Tristan da Cunha, a tiny speck of land best known for being the world’s most remote permanent settlement and for a 1961 volcanic eruption that required the entire population to be evacuated to Surrey for several months. Astonishingly, Tristan da Cunha (with a population of 264 and no resources) has been financially self-sufficient since 1980. That’s all thanks to two key economic powerhouses—a crayfish factory and the local post office, which sells its stamps around the world. At one point, half of the island’s income was coming from stamp sales. This is especially impressive considering that the first Tristan da Cunha stamp, introduced in 1942, had to be priced in potatoes or cigarettes due to a lack of money on the island.

4The Court Jester Who Almost Bankrupted Tonga

Another isolated Pacific island state, the Kingdom of Tonga struck gold in the 1980s, when it started selling passports to Hong Kong residents who were worried about the city’s upcoming handover from Britain to China. The scheme ultimately brought in millions, which King Taufa’ahau Tupou IV simply deposited with Bank of America. When a bank employee named Jesse Bogdonoff stumbled onto a ordinary checking account with over $20 million sitting in it, he was so astonished that he immediately contacted the king and quickly became his investment adviser. At his own request, he was also appointed Tonga’s official court jester.

Things went swimmingly at first, with the booming investment climate of the 1990s allowing Bogdonoff to make a solid profit, although his previous financial experience mostly consisted of a business selling “healing magnets” for curing back pain. But a series of risky gambles followed, and Bogdonoff had soon invested almost the entire $25 million fund in the life insurance policies of Americans with terminal diseases. That didn’t turn a profit. As a financial crisis broke out in Tonga, Bogdonoff was accused of raking off $8 million in secret commissions. He subsequently lost a court case, but that didn’t help Tonga, which was left with a devalued currency, diminished foreign reserves, and a discredited king. To make matters worse, they didn’t even make a movie about the incident, even though the court settlement specifically gave Tonga 50 percent of the rights to Bogdonoff’s life story.

3Saint Lucia Keeps Switching Between China And Taiwan

In 1949, the government of the Republic of China fled to Taiwan to escape the advancing communist forces of Mao Tse-Tsung. The two countries have had a strained history since then, with both claiming to be the sole legitimate government of China and consequently refusing to acknowledge the other’s existence. This has been bad news for East Asian politics but fantastic news for the smallest nations in the world, which have frequently profited by flipping recognition (and valuable votes in the UN and other international bodies) between China and Taiwan.

In 2004, the Caribbean island of Dominica switched recognition from China to Taiwan in return for $110 million in aid over the next six years. Dominica’s entire GDP is around $790 million per year. Grenada confirmed its support for Taiwan in 2003 but switched to China in 2005. The region had just been slated to host the 2007 Cricket World Cup, and China offered to fund the expensive new stadium that Grenada needed for the matches. Over in the Pacific, Nauru and Tonga secured big aid deals from China, while Kiribati switched allegiances to Taiwan in return for economic assistance. In 2011, Vanuatu announced a hefty budget shortfall and suggested that it might open a trade office in Taiwan. The irritated Chinese government eventually agreed to pay part of the shortfall in exchange for Vanuatu reaffirming its commitment to China.

But when it comes to flip-flopping recognition, nobody can match the Caribbean island of Saint Lucia. The country had sided with Taiwan since 1984 but decided to recognize China in 1997. Naturally, China sweetened the deal with a big assistance package (and a new cricket stadium), but the Saint Lucians were underwhelmed when Chinese tourists failed to show up in any numbers. Additionally, Taiwan had run a very effective agricultural development program, which local farmers soon began to miss. So, in 2007, Saint Lucia thanked China for all their help and promptly switched back to Taiwan, which they hoped would help “diversify agriculture, boost tourism, develop livestock, and create information technology learning centers” on the island.

2Eritrea Loves Extortion

A small East African nation around the size of Cuba, Eritrea has a reputation as one of the worst dictatorships in the world. Naturally, this has prompted a large percentage of the population to flee the country for a better life abroad. However, simply escaping overseas often isn’t enough to escape from the Eritrean government, which quickly realized that the growing refugee community could actually be a great source of foreign exchange.

This is the reason for Eritrea’s terrifying “diaspora tax,” which requires all Eritreans living overseas to pay 2 percent of their yearly income to the brutal government that they probably fled. A United Nations report found that collecting the money “routinely involves threats, harassment, and intimidation” carried out by Eritrean consulates and government representatives around the world. According to a Canadian investigation, refugees can expect to have any friends or family members still in Eritrea threatened until they pay up. Eritrean consulates often refuse to renew passports or transfer important documents like school transcripts until all “arrears” are handed over.

To make matters worse, the Eritrean government allegedly uses some of the money to support Islamic militant groups like Somalia’s Al-Shabab in order to destabilize their rivals in Ethiopia. Despite a full UN resolution condemning the tax, the practice has proven hard to stop. Canada expelled Eritrea’s consul-general in 2013, but the extortion was still going on a year later. In the UK, the Eritrean embassy agreed to stop collecting the tax, but it really just switched to insisting that it be paid in Eritrea rather than the UK. Eritreans who wanted to send money home to support their families were left with no choice but send extra money to pay the tax.

1Antigua Dabbled In Arms Dealing

In 1989, an order arrived in Israel for roughly 10 tons of weapons, including 100 Uzis and 400 assault rifles, in order to equip the Antigua and Barbuda Defense Force (ABDF). That should have raised suspicions, since the ABDF only had 70 members, and they were already equipped by the United States. An Israeli military officer accompanied the weapons to Antigua, an idyllic Caribbean island with a population of about 80,000, but apparently raised no objections when the locals quickly loaded the weapons onto a different ship.

A few months later, Medellin cartel leader Gonzalo Rodriguez Gacha was killed in a shoot-out with the Colombian police, who subsequently discovered the weapons. Suspicion quickly fell on the prime minister of Antigua, Vere Bird, whose oldest son had apparently signed the weapons order. A subsequent investigation suggested that the scheme was probably the brainchild of Maurice Sarfati, an Israeli who ran a failing melon farm on Antigua. Sarfati had grown close to the Bird family, who appointed him to a succession of lucrative government posts.

The weapons deal was only supposed to be the start. Plans were also afoot to use the ABDF as cover to establish a “security training school,” which the official report into the incident concluded was obviously intended “to train mercenaries in assault techniques and assassination.” It was widely suggested that the cartels also intended to use the camp to train Tamil rebels from Sri Lanka in exchange for help with entering the Asian heroin trade.

Fortunately, the discovery of the weapons halted that plan in its tracks. The international scandal badly damaged the reputation of the Bird government. Vere Bird Jr. was forced to resign as a government minister, and Vere Bird Sr. didn’t run for reelection. Instead, Antigua elected his second son, Lester Bird, who mysteriously failed to clean up corruption on the island.