Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Niche Subcultures That Are More Popular Than You Might Think

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Tragic Disappearances and Deaths in Joshua Tree National Park

History

History 10 Ways Childhood Really Sucked in the Old West

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Music

Music 10 Name Origins of Famous Bands from the 1990s

Religion

Religion 10 Biggest Turnarounds by the Catholic Church

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Unbelievable Times Laws Had Unintended Consequences

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Women Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Films That Spawned Major Lawsuits

History

History Ten Times Towns Were Wiped Off the Face of the Earth

Creepy

Creepy 10 of the Most Disturbingly Haunted Public Houses in the UK

10 Pivotal Days That Turned The Tide Of The Crusades

“The Crusades” is a pretty all-encompassing term that can be used to describe a handful of holy wars throughout the Middle Ages. Even though they were driven mostly by religion, there were a host of other reasons why knights, lords, princes, and peasants alike took up their weapons in the name of God; there were a handful of days that changed the course of the Crusades—and of history—forever.

10The Siege And Fall Of Acre

May 18, 1291

Acre is an incredible city, located in Israel in Western Galilee. It’s been occupied since at least 1900 B.C., and the city that stands today dates back to around the 18th century. Buildings have been long built on top of buildings, though, and buried somewhere under the more modern city are the remains of one of the Crusader strongholds of Israel.

Acre changed hands repeatedly throughout the Crusades. First held by the Christian Crusaders beginning in 1104, it was retaken by the Muslims in 1187. Soon after, Richard the Lionheart prepared to descend on the entire area, and he succeeded in taking it back in 1191. While it was held by the Crusaders, its defenses were expanded, churches were built, and it became the capital of the Christian presence in the area.

Cities were sacked repeatedly throughout the Crusades, but Acre was a huge stronghold. It served as the headquarters not only of the Crusade itself, but also of all the heavy hitters of the Christian military. The Hospitallers, the Templars, and the Teutonic Knights all had headquarters there, and when the siege broke the city on May 18, 1291, the defenders would never recover. The Templars saw the death of their Grand Master, the Hospitallers fled with their wounded leaders, and most of the members of the Teutonic Knights were killed. Those few that did survive returned to Italy and Cyprus, and attempts at re-grouping and taking back the land that they had lost were never successful. The fall of Acre wasn’t just the sacking of another city; it was the loss of the foothold and the heartbeat of Christian territory, and it never recovered.

9Peter The Hermit

August 1, 1096

When Pope Urban II called for a holy war against the infidels in the east, it was Peter the Hermit who led the charge and who set the tone for the rest of the Crusades.

Peter the Hermit was one of the many preachers who was used to raise popular support for the Crusades. Contemporary chroniclers describe him as a small, dark man who rode a mule between the villages that he would stop to preach at. He was so good at his job that he didn’t just raise public opinion—he raised an army.

People were in such a hurry to head off to the Crusades that they didn’t want to wait for the Pope’s send-off or the Pope’s army, so instead of waiting for a proper military effort organized by the nobility and the clergy, they all marched off on their own. By April, Peter and his 13,000-strong army made it to Cologne. Some went ahead even farther, under a man we only know as Gautier Sans-Avoir.

By August 1, 1096, Peter made it to Constantinople, but the journey wasn’t a peaceful one by any means. He accepted everyone into his army, and that included those who had nowhere else to go—which meant that there was plenty of killing, looting, and pillaging happening all the way through Germany, Hungary, and the Byzantine Empire.

It was on August 1 that things started to go permanently sideways. Ever the optimist, Peter had arranged to have his improvised army ferried across the Bosporus Strait. Once his troops started getting to the other side, though, people split off into their own groups and the Turks began picking them off one isolated group at a time.

8Indulgences

November 25, 1095

Indulgences have long been a huge topic of debate when it comes to questionable practices of the Catholic Church. They’re essentially a get-out-of-jail-free card—do the right thing or pay the right people, and you were guaranteed a place in Heaven.

The whole thing started on November 25, 1095, with a declaration from Pope Urban II. He really wanted his war, but in order to get it, he needed bodies. In a sermon given to a group of people in Clermont, France, Urban declared that anyone who went off to the Crusades and fought the non-Christians—and then confessed their sins in good Catholic form—would be automatically forgiven.

It was the start of a practice that would call into question the ethical values of the Church, since the decree sent the message that you could do anything with the Church’s approval as long as the end goal was an acceptable one. Eventually, people who weren’t able to actually go and fight wanted salvation for their contributions, too, and the promises were extended to anyone who donated money to the cause. According to the pope, it was a just war. And if the pope said it, then it must be true.

7Stephen Of Cloyes

Easter, 1212

All too often, children are on the front lines during war, and that was no different in the Crusades—at least, that was the intention of many.

In 1212, thousands of young teenage boys turned their backs on their farming duties and headed off to the Holy Land to fight in what came to be known as the Children’s Crusade. It didn’t go well. Most were turned back at various stages along the way, although some French children made it as far as Rome before they were sent home.

Around Easter in 1212, a boy named Stephen of Cloyes began to preach. According to Stephen, he had been visited by Christ in a dream, who had instructed him to head to the Holy Land. He said that he’d been given a holy “letter,” so he gathered up a small army of his own believers and headed to Paris to relay the contents of the message to King Philip II. The king refused to listen and sent them home, but not all of them did what they were told.

Not surprisingly, just what happened to all the children isn’t known for sure. We do know that thousands headed off in July 1212, led by a boy named Nicholas. Some turned back, some died horribly along the way, and, according to the chronicler Alberic of Troisfontaines, hundreds died when the ships they had boarded near Sardinia sank. Others were said to have been sold into slavery. Whether or not any of these stories are true is hard to say, since there are plenty of myths about the Children’s Crusade. But given that there are no records of any teenage fighters in the Holy Land, it’s safe to assume that the attempts of the young Crusaders were ultimately in vain.

6Frederick Barbarossa

June 10, 1190

We’ve talked a little bit about how German king Frederick Barbarossa drowned while trying to cross a river. While his death was a blow to the German people, it also impacted the campaign in the Holy Lands.

Barbarossa was riding at the head of a German army en route to the Holy Land through Constantinople and the Taurus Mountains. The army was marching at the behest of Pope Gregory VIII, and was to fight side by side with the French and English armies of Philip Augustus and Henry II. The situation was dire, with only one major stronghold remaining in Tyre. Their forces were not only exhausted, but Saladin and his troops had time to rest and recuperate before marching in for the final blow.

The combined forces were intimidating, and getting them to stand together was no small feat. The English and the French had put aside their differences—and their constant war—to ally against Saladin. The peace was short-lived and not nearly as amicable when Henry II was replaced by his son, Richard. The Germans were in the middle, and they were well-trained, disciplined, and well-equipped.

Barbarossa’s death changed all that.

The army split. Some returned home and some went to Tripoli. The heir to the throne headed to Cilicia, in Asia Minor, to bury at least parts of his father. Some of the army even gave up their Christianity, saying that the death of their king was a clear sign that God had frowned on their mission.

5Saladin And Raynald

July 4, 1187

At the head of the Crusader presence in the Holy Land in 1187 was Raynald de Chatillon, who had long had a reputation as every kind of nasty there was. He had already spent a decade and a half in jail for his various crimes, and his way of honoring a tenuous treaty between Saladin and the Crusaders was looting and pillaging whatever he and his men could get his hands on. When it came time for Saladin to move on re-conquering Jerusalem, he started with Raynald.

Saladin’s forces sacked the city of Tiberius, drawing Raynald and his king, King Guy, toward the city. They never got there, though, as Saladin and his army engaged them instead at the Horns of Hattin and thoroughly decimated them in a violent six-hour battle. Guy and Raynald were brought to Saladin’s tent.

According to the chronicler Baha al-Din, Saladin offered the king a drink of water. The king, in turn, passed it on to Raynald. While the king was protected by the custom and honor of hospitality laws, Raynald was not, and Saladin beheaded him himself.

Those that swore an oath not to take up arms against Saladin and his men again were released, the Templars among the group were executed. The July 4 rout left Jerusalem all but undefended, and Saladin took it on October 2 of the same year.

4The Tournament Of The Fourth Crusade

November 28, 1199

In 1199, the church was putting together the Fourth Crusade. But, like those before, they needed the support of the nobility, the arms of the knights, and the enlistment of the fighting men. To get these, they decided to hold a tournament.

On November 28, 1199, France’s elite gathered at Ecry-sur-Aisne for what was advertised as the height of chivalry and honor, of entertainment, of courtly life. On the tournament battlefield, though, it was still a bloody, brutal battle where men carried real weapons and lances weren’t designed to break on impact. The melee was still popular, hundreds of men on the battlefield at a time, all looking for glory with no rules that needed to be followed. And after the tournament (and after the dead and the wounded had presumably been taken away), the victors told stories, sang songs, and remembered the good old days.

Both the hosts of the tournament had family that had fought in the Crusades, and one, Count Louis of Blois, had already fought in one. His father had died in the same Crusade, and the other man, Count Thibaut of Champagne, also had a father who had been high in the ranks in Jerusalem. He’d later been pulled off a balcony by his court dwarf and killed.

The tournament had been well thought out, and there were few better places to foster a sense of camaraderie than on the mock battlefield. It wasn’t long before the nobility that the church needed was signing up to take the cross, and set off on what would be the Fourth Crusade.

3The Great Schism

September 20, 1378

On September 20, 1378, 13 cardinals decided that enough was enough, and the acting Pope Urban VI wasn’t the pope they wanted in office. Instead, they elected a new pope—Pope Clement VII—to take a seat at Avignon, creating the Great Schism.

Just what happened to make the 13 cardinals turn on their elected pope is up for debate, but historians think that it had something to do with Urban VI’s pretty bad attitude. While he might have been quite literally holier-than-thou, he acted it, too, suspicious of those beneath him and not afraid to lash out at his colleagues, whether he had anything to support his accusations or not. Gradually, the disaffected cardinals withdrew from Rome to Avignon and appointed their own pope—which, of course, caused some problems within the Church.

Both popes had saints on their sides, while many of the royals sided with the newly appointed Clement VII (pictured above). While the Catholic community was divided, the popes themselves were busy excommunicating each other, creating new cardinals, and trying to gain support.

Amid all the fighting, there was a group that was of the mind that what the Church needed to pull itself back together was a good old Crusade, because nothing united people like a common enemy. St. Catherine of Siena, who had always sided with the original Pope Urban VI, was one of the most outspoken proponents of another Crusade in hopes of bringing the rebel cardinals back into the flock.

The Great Schism only ended in 1417, with the election of Pope Martin V. In the meantime, there was a series of Crusades led against the Ottoman Turks, Mahdia, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Syria.

2The Crusading Bull

December 1, 1145

One of the most enduring images of the Crusaders is that of an army marching across Europe and into the Middle East, burning, pillaging, and pretty much destroying anyone and anything in front of them, all in the name of religion. They were once said to be carrying out the work of God, but by the Second Crusade, it was clear to those that were in their way that that’s not necessarily what was going on.

That was largely thanks to Pope Eugenius III. On December 1, 1145, he issued a summons to a Crusade, calling for what would ultimately become the Second Crusade. In his speech, he says that it had become necessary to honor all those that had gone before, who had died for the right of Christians to spread their beliefs and practice those beliefs in peace. He talked about the Christians that had been killed by the infidels, about the saints’ relics that had been defiled, and the blood that had been shed.

And he also promised those that fought in the Crusades the same privileges as the clergy—and that was no small thing. That meant that Crusaders would have debts removed, would not have to pay interest on loans, and would get out from beneath the burden of taxes. And that was in addition to the freedom of having their sins lifted when they confessed, because whatever was done in the name of freeing the Holy Land from the infidels was, quite clearly, all right by God.

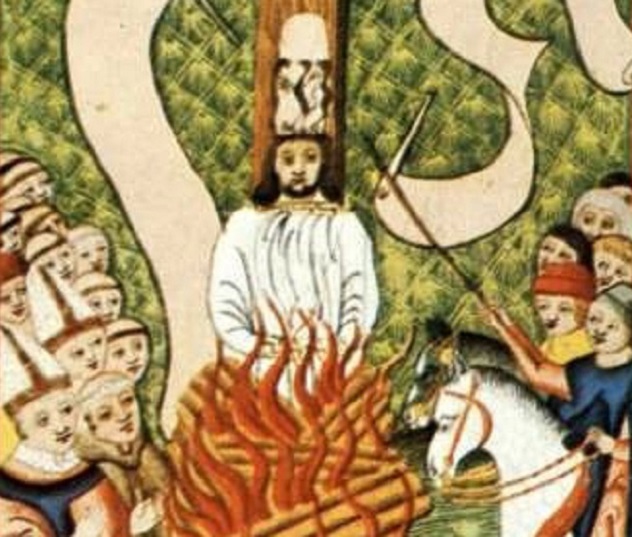

1Jan Hus

July 6, 1415

Not all the Crusades were based in the Middle East, and the death of one man on July 6, 1415 started the Church down the path toward a Crusade into Czechoslovakia. Jan Hus was a pretty revolutionary Czech priest, and if there’s anything the Catholic Church doesn’t approve of, it’s revolutionary thought. Hus was burned at the stake for his non-traditional views (which included the idea that the Church wasn’t the most moral of institutions), and for his followers, things went downhill from there.

Killing Hus had made him a martyr. The University of Prague issued a statement supporting him, calling his death nothing more than a murder at the hands of the Church. Nobility and peasantry alike took up his views, and the Hussites started to grow. By 1418, Pope Martin V had started a Crusade not against the infidels in Jerusalem, but against the rebel Christians in Bohemia. Before it was over, five different Crusades would be taken beneath the Catholic banners and against the Hussites, with the sole purpose of stamping out the growing influence of the man they had burned at the stake a few years before.

Thousands would die before the Hussites would rout the Crusaders in the fifth of the Hussite Crusades. It was, perhaps, the most bizarre Crusade of them all, with Christians fighting Christians, declaring each other heretics and immoral, and killing in the name of a holy war defending the same God.