Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous  Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous  Our World

Our World 10 Green Practices That Actually Make a Difference

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Men Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV The 10 Most Heartwarming Moments in Pixar Films

Travel

Travel Top 10 Religious Architectural Marvels

Creepy

Creepy 10 Haunted Places in Alabama

History

History Top 10 Tragic Facts about England’s 9 Days Queen

Food

Food 10 Weird Foods Inspired by Your Favorite Movies

Religion

Religion 10 Mind-Blowing Claims and Messages Hidden in the Bible Code

Facts

Facts 10 Things You Never Knew about the History of Gambling

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous Ten Groundbreaking Tattoos with Fascinating Backstories

Our World

Our World 10 Green Practices That Actually Make a Difference

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Men Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV The 10 Most Heartwarming Moments in Pixar Films

Travel

Travel Top 10 Religious Architectural Marvels

Creepy

Creepy 10 Haunted Places in Alabama

History

History Top 10 Tragic Facts about England’s 9 Days Queen

Food

Food 10 Weird Foods Inspired by Your Favorite Movies

Religion

Religion 10 Mind-Blowing Claims and Messages Hidden in the Bible Code

Facts

Facts 10 Things You Never Knew about the History of Gambling

10 Surprising Modern Discoveries At Important Historical Sites

Every year, there are more discoveries that change the way we see history, and some of these are in places that were long considered to be fully documented. Whether it was a lack of knowledge or a finding completely out of the blue, our most well-known sites still yield discoveries that would have never been found if we hadn’t investigated further.

10 Acres Of Clothing In A Forest Outside A Concentration Camp

For 60 years, an enormous trove of concentration camp history remained missing. In 2015, a group of hikers in Poland made a shocking discovery: acres of discarded prison clothing and other articles related to a tragic location nearby. Near the forest where the unsuspecting tourists made their discovery was an infamous Nazi prison camp: Stutthof.

The most surprising part of the discovery was that most of the clothes were found in plain sight. The Stutthof death camp is now a museum and has a fairly large number of visitors and researchers who all overlooked the artifacts. No real sleuthing was needed; apparently, the forest was not explored since it became the sight of genocide during the Nazi reign.

All sorts of clothing articles were found: shoes, belts, pants, shirts, etc. Stutthof housed 110,000 prisoners throughout history, 85,000 of whom died there. Experiments on their body fat were used for soap production, which adds an ever more gruesome angle.

Apparently, their clothes weren’t worth keeping since they were dumped into the forest surrounding the camp, a fact many historians were not aware of. One fact was quite surprising: the prisoners’ shoes were leather, not wooden clogs as at most prison camps. No one who worked around the camp ever noticed the clothes, and there had been no rumors about them before their discovery.

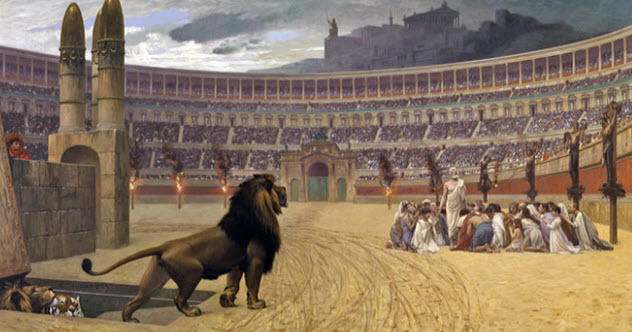

9 Elaborate Man-Made Elevators At The Colosseum

For centuries, archaeologists have been puzzled as to the purpose of a series of tunnels creating a confusing labyrinth beneath the Roman Colosseum. Apparently, the tunnels were all carefully built to lead to more chambers in various ways. Ultimately, they led beneath the arena where trapdoors went into the fighting area. It is clear that they were built like this intentionally, and in 2011, after 14 years of research, their purpose was finally discovered.

According to German archaeologist Heinz-Jurgen Beste, the hypogeum (Greek for “underground”) served as an elaborate way for animals and warriors to appear from beneath the floor without being noticed by those in the audience. To put in perspective how effective the system was, during a spectacle by Emperor Trajan, 11,000 animals were put through the hypogeum and killed. It was a form of theatrical trickery that would be unmatched for centuries.

It had been there since the Colosseum was first completed in AD 80, but its original purpose was forgotten after the Roman Empire fell. Over the centuries, the hypogeum has seen various uses: a place to store hay, underground gardens, and stalls for businesspeople. Throughout this time, it slowly crumbled until Mussolini took power and had the tunnels cleared.

In 1996, archaeologists started to restore the tunnels. We now know just how intricate they were. They were operated by a series of levers, ropes, and pulleys that created almost impossible spectacles. Even today, many theaters are not as elaborate or creative as the Colosseum was with the hypogeum, which just goes to show how intelligent and clever our ancient ancestors really were.

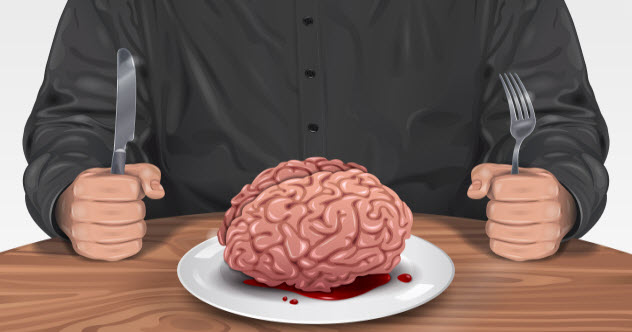

8 A Cannibalized Body At Jamestown

Jamestown, Virginia, is known as the first permanent English colony in America. It is now one of the most revered historic spots in the United States, and many researchers still go there to unlock more secrets from that time.

However, in summer 2012, historians made a disturbing discovery in a hole that contained butchered horse and dog skeletons. They knew immediately that this hole had probably been dug during a severe famine, but what they found when they dug deeper only shocked them further.

The body was that of a 14-year-old English girl who had undoubtedly died in winter 1609. The winter was so harsh and the food supplies so low that it became known as the “starving time”. It was well-documented how far the colonists of Jamestown went. In 1625, George Percy, governor of Jamestown during the starving time, wrote a letter describing how colonists ate their horses, vermin, and even leather boots. He then went on to say that some had even dug up the dead in desperation.

The young girl found in 2012 was the victim of this starvation. There had been strikes to the back of her head to get to her brain, which would be the most desired tissue. The attempts were clumsy by whoever was trying to harvest her flesh. It was clear that the person had never done this before.

The details of her death are unknown. Was she murdered by another desperate colonist, or had she died of natural causes and been disturbed from the grave? We will probably never know.

7 A Mass Graveyard At Bedlam Asylum

“Bedlam” is now an offhand way of referring to insanity, but at one time, Bedlam was one of the most important mental asylums in the world. In centuries past, mental illness was virtually untreatable and those who were considered harmful were locked up at Bedlam.

It still has its infamous reputation due to the archaic treatments that took place there and the extremely poor conditions. But many have never thought about where the patients were later buried. In 2015, the answer was uncovered.

While digging near Bedlam Asylum at a location that would become the Crossrail’s Liverpool Street station, workers came upon a horrific sight: a mass grave filled with 30 skeletons. A headstone read only “1665,” and it became clear that this was a repository for victims of the Black Plague who had been isolated at Bedlam.

Since excavation first started, an estimated 3,500 corpses have been dug up, although historians estimate that a staggering 30,000 might be waiting to be discovered. This cemetery was in use for almost 200 years—from 1569 to 1738. It was unlike other cemeteries near Bedlam because it was mostly one body on top of another rather than individual graves.

It served as a burial place for the outcasts of English society: those without a religion, family members, or the financial means for a private burial. In 1665, during a particularly infamous outbreak of the plague, it served as a dumping ground for victims of the plague because other cemeteries were simply overflowing.

6 Buried Gas Chambers In Poland

While digging up a road near Sobibor concentration camp, archaeologists made a shocking discovery: a series of gas chambers that had been hidden since the end of World War II. The chambers have a sad history: They were the place of death for an estimated 250,000 Jews who were imprisoned at Sobibor. The archaeologists also found personal items of the victims.

Although the chambers had been buried under an asphalt road, archaeologists used the remaining outline to estimate the size of the chambers and the number of victims that could have been inside. Personal items like a wedding ring were found nearby—even more evidence that the Nazis had tried to cover up before they were defeated.

As Sobibor was efficiently destroyed and few prisoners survived there, we have little information about the camp when compared to others. Eight gas chambers have been discovered, and it took just 15 minutes to kill the victims inside when the chambers were operating. Supposedly, the Germans bred geese to drown out the screams of the victims. The entire concentration camp was demolished after a prisoner uprising in 1943, so the gas chambers are all that remain.

5 Baby Remains At The Yewden Villa

Almost 100 years ago, archaeologists discovered Yewden Villa, a massive Roman villa underneath the English town of Buckinghamshire. For whatever reason, the old archaeologists covered up the villa’s most gruesome relics along with the ruins. They soon forgot about the find, and it took a century for its possessions to be rediscovered.

When Dr. Jill Eyers was going through a museum storeroom in 2008, she unexpectedly rediscovered the remains of 97 infants that had been found at Yewden Villa. There have been many theories about why the infants were found there. From testing on the remains, the infants probably died between a 50-year period from AD 150 to AD 200. Eyers’s theory is that the villa was used as a brothel and that the children, as sickening as it sounds, were simply abandoned by their mothers.

Another theory is that the villa was used in rituals performed by a mother goddess cult and that the infants were a part of it. They were probably stillborn, and their mothers took them to beg the goddess of fertility for healthy children.

Cut marks discovered on the bones could indicate many things: human sacrifice, defleshing before burial, or even dismemberment of the fetus to save the life of the mother. As the Yewden Villa is now buried beneath a field, we won’t know the reason for the infants’ burial there until the site is excavated again.

4 An Aristocratic Burial Ground At Stonehenge

Stonehenge has long mystified the world. A prehistoric monument in England, it is one of the most iconic historical sites in the world. Despite its prominence, we are still mostly in the dark as to its true purpose. Why was it built? Who built it? How was it built? All these questions have multiple different answers, but a discovery this year might shed some light.

During an excavation of a chalk pit near Stonehenge known as Aubrey Hole 7 (there are 56 such pits around Stonehenge), archaeologists discovered a burial ground that held the bodies of 14 females and 9 males, all of whom were at least young adults. It has long been theorized that Stonehenge might be some sort of cemetery for highly respected, aristocratic individuals of the time.

Finding prehistoric cemeteries is extremely rare. Only the most powerful people of the time would have been buried with such respect. The discovery at Aubrey Hole 7 has been dated as far back as 3000 BC, and the fact that women were buried in the same place as men has changed historians’ perspective of gender roles of the time. It shows that women were treated with the same respect as men, something not seen by most cultures of the time. Along with this revelation, it also proves the theory that Stonehenge served as a sort of monument for the dead.

3 Proof Of A Mythical War At An Incan Fortress

In the mountains of Ecuador, the 500-year-old Incan fortress Quitoloma stands as the only survivor of a 17-year war that was long forgotten by historians. The fortress is well-equipped for battle: It contains areas for weapons storage along with 100 structures for occupation. It is sturdy and built from solid stone. From this fortress, historians have pieced together 19 others belonging to the Inca that were used against their adversaries the Cayambe.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the Spanish conquistadors spoke of a war between the Incas and their neighbors which has been regarded by most as nothing but folklore. However, with the discovery of the multiple fortresses, many are reconsidering their opinions on the matter.

The Incan fortresses tower 3,000 meters (10,000 ft) in the air and were built from stone while the Cayambe fortresses were built from a strong volcanic rock known as cangahua. The fortresses were long forgotten, but their proximity fits the Spanish descriptions of a war that was particularly brutal and lasted an incredible 17 years.

The fortresses were only recently discovered, so more excavation and study is needed. But as it stands, it is clear that the mythical war did indeed happen. However, within a few decades, both of the enemies would face the far superior Spanish forces who easily put them both into submission.

2 Decapitated Gladiators In Ancient London

In 1988, 39 human skulls were discovered at the London Wall—just a short distance from their future home, the Museum of London. They remained a mystery for 25 years while historians tried to determine in which year the skulls were buried and why these people were executed at all. It was found that they were Roman-era fossils, which puts them around the time of Britain’s Roman occupation.

The skulls have been dated from AD 120 to AD 160, and these people most certainly had gruesome deaths. For example, one skull showed signs of a brutal attack by dogs. Due to forensic advances over the years, it was found that all of the skulls displayed some kind of damage from a violent conflict.

Since decapitation was the most common form of execution for defeated gladiators, researchers determined that they were most likely just that. Near the area where the skulls were discovered, an amphitheater stood, which gives even more credence to the gladiator theory.

Disturbingly, the executed gladiators had their heads dumped into open pits, which explains why they were concentrated in single areas. They were left to rot, which explains why animals like dogs would eat their remains. The second century AD was one of the most peaceful times for Roman-era London, but it quite clearly wasn’t so peaceful for everyone.

1 2,000 Bones Beneath Oxford’s Museum Of The History Of Science

The Museum of the History of Science at Oxford does have bones, but they’re on exhibit, not buried beneath the museum. In 1999, the restoration of the museum led to an excavation of the basement, which was built in the 17th century. A stone well and two concrete pits were found, which museum historians had been unaware of. In the concrete pits, old artifacts were found, including chemical vessels and 2,000 bones.

Among the 2,000 bones, 15 humans were found, including three fetuses. Meanwhile, 800 animal bones identified as canine were also discovered. Why were these bones in the basement of the museum? The reason is actually very simple: They were needed for dissection.

In 1710, a German man named Zacharias Conrad von Uffenbach recorded a dissection that he had attended in the basement of the Oxford museum. Known originally as Solomon’s House, it was built in 1683 and was supposed to be for experimental natural philosophy, of which dissection was a key part.

At the time, the only legitimate source of human bodies was executed criminals from the gallows. However, seeing the variety of ages among the bones (ranging from fetus to elderly), it seems that they may have been obtained illegally.

When bodies couldn’t be found, dogs or badgers were used. Interestingly, an African manatee was found and may have been put on display as a mermaid. Once the dissections were complete, the bodies were apparently dumped into pits beneath the museum and covered up.

![Top 10 Most Important Nude Scenes In Movie History [Videos] Top 10 Most Important Nude Scenes In Movie History [Videos]](https://listverse.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/sharonstone-150x150.jpg)