History

History  History

History  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

Top 10 People Made Famous By Their Deaths

Andy Warhol once said that every man would have 15 minutes of fame – unfortunately for the 10 people on this list, that fame came at a high price – their life. These are people who would undoubtedly prefer to have lived without fame than lose their lives to achieve immortality in history.

Pasqualino Antonio “Leno” LaBianca and his wife Rosemary LaBianca were victims of the Manson Family murders famously known as the Tate LaBianca murders. Charles Manson, the leader of the Manson “family,” orchestrated the murders for the sake of Helter Skelter, an apocalyptic war he believed would arise from tension over racial relations between blacks and whites. The four “family” members who had participated in the Tate murders, Charles “Tex” Watson, Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel and Linda Kasabian, were again summoned by Manson along with Leslie Van Houten and Steve Grogan aka Clem Tufts. Manson ordered Kasabian to cruise the neighborhoods of Los Angeles, in search of potential victims, before settling on the home of the LaBiancas.

Sometime during the early morning hours of August 10, 1969, Manson family members entered the LaBianca house and murdered the couple. The girls wrote messages in Leno’s blood. “Death to pigs” and “Rise” were written on the living room wall, and “Healter Skelter” [sic] was written on the refrigerator. After the murders, the family members remained at the house. Some ate food from the LaBianca’s refrigerator, played with the couple’s dogs and showered before hitchhiking back to the Spahn Ranch.

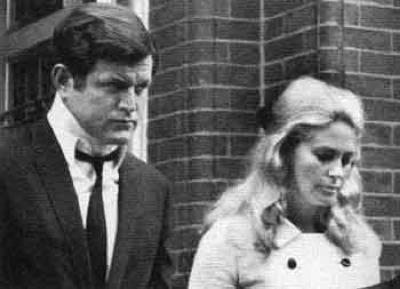

Mary Jo Kopechne was an American teacher, secretary and administrator, who died in a car accident in Chappaquiddick Island while being driven by United States Senator Ted Kennedy. On July 18, 1969, Kopechne attended a party on Chappaquiddick Island, off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, held in honor of the “Boiler Room Girls.” This affectionate name was given to the six young women who had been vital to the late Robert Kennedy’s presidential campaign and who had subsequently closed up his files and campaign office after his assassination.

Kopechne left the party at 11:15 p.m. with Kennedy after he allegedly offered to drive her to catch the last ferry back to the Katama Shores Motor Inn in Edgartown where she was staying. Kennedy stated, on his way to the ferry crossing back to Edgartown, that he accidentally turned right onto Dike Road – a dirt road – instead of bearing sharply left on Main Street. After proceeding one-half mile, he descended a hill and came upon a narrow bridge set obliquely to the unlit road. Kennedy drove the 1967 Oldsmobile Delmont 88 belonging to him, off the side of Dyke Bridge, and the car overturned into Poucha Pond. Kennedy extricated himself from the submerged car but Kopechne died.

J. D. Tippit was a police officer with the Dallas, Texas Police Department who, according to numerous witnesses and multiple government investigations including the Warren Commission, was shot and killed by Lee Harvey Oswald after Tippit stopped Oswald following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

At approximately 1:11–1:14 p.m. on the day of the assassination, Tippit was driving slowly in an easterly direction on East 10th Street in Oak Cliff. Tippit pulled up alongside Oswald, who was walking in the same direction. Oswald then walked over to Tippit’s car, and apparently exchanged words with him. Tippit opened the door on the left side and started to walk around the front of his car. As he reached the front wheel on the driver’s side, Oswald drew a revolver and fired several shots in rapid succession, hitting Tippit three times in the chest. He then walked up to Tippit’s fallen body and shot him directly in the head, killing him instantly.

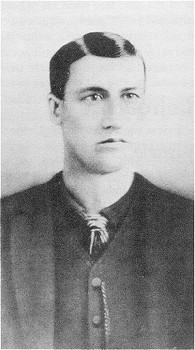

John Morrison Birch was an American Military Intelligence Officer and a Baptist Missionary in World War II who was shot by armed supporters of the Communist Party of China. Some politically conservative groups within the United States consider him to be a martyr and the first victim of the Cold War. The John Birch Society, formed thirteen years after his death, is named in honor of him.

Birch is known today mainly by the society that bears his name. His name is on the bronze plaque of a World War II monument at the top of Coleman Hill Park overlooking downtown Macon, along with the names of other Macon men who lost their lives while serving in the military. Birch has a plaque on the sanctuary of the First Southern Methodist Church of Macon, which was built on land given by his family, purchased with the money John sent home monthly. Pictured above is Robert Welch, chief organizer of the John Birch society.

Edward Donald Slovik was a private in the United States Army during World War II and the only American soldier to be executed for desertion since the American Civil War. Although over twenty-one thousand soldiers were given varying sentences for desertion during World War II—including forty-nine death sentences—only Slovik’s death sentence was carried out. Slovik was charged with desertion to avoid hazardous duty and court martialed on November 11, 1944. The prosecutor, Captain John Green, presented witnesses to whom Slovik had stated his intention to “run away.” The defense counsel, Captain Edward Woods, announced that Slovik had elected not to testify. The nine officers of the court found Slovik guilty and sentenced him to death.

On December 9, Slovik wrote a letter to the Supreme Allied commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, pleading for clemency. However, desertion had become a problem, and Eisenhower confirmed the execution order on December 23. The execution by firing squad was carried out at 10:04 a.m. on January 31, 1945, near the village of Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines. Slovik was twenty-four years old.

Horst Ludwig Wessel (October 9, 1907 – February 23, 1930) was a German Nazi activist who was made a posthumous hero of the Nazi movement following his violent murder in 1930. He was the author of the lyrics to the song “Die Fahne hoch” (“Raise High the Flag”), usually known as Horst-Wessel-Lied (“the Horst Wessel Song”), which became the Nazi Party anthem and Germany’s official co-national anthem from 1933 to 1945. The song was banned along with all other Nazi symbols in 1945, and both the lyrics and tune remain illegal in Germany to this day. The clip above shows the song being sung at the Nuremberg Congress.

John Luther “Casey” Jones was an American railroad engineer from Jackson, Tennessee who worked for the Illinois Central Railroad (IC). On April 30, 1900 he alone was killed when his passenger train collided with a stopped freight train at Vaughan, Mississippi on a foggy and rainy night. His dramatic death trying to stop his train and save lives made him a railroad icon who became immortalized in a popular ballad sung by his friend Wallace Saunders, an African American engine wiper for the IC. Due to the enduring popularity of this classic song, he has been the world’s most famous railroad engineer for over a century.

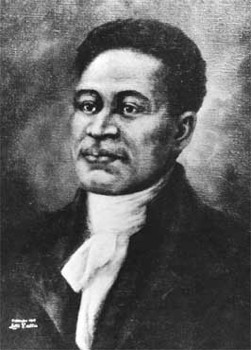

was one of five people killed in the Boston Massacre in Boston, Massachusetts. He has been frequently named as the first martyr of the American Revolution and is the only person killed in the Boston Massacre whose name is commonly remembered. Although little is known for certain about Attucks, including his ethnicity, the possibility that he was African American or Native American has elevated him to an important symbolic status in U.S. history.

In the early 19th century, as the Abolitionist movement gained momentum in Boston, Attucks was lauded as an example of a black American who played a heroic role in the history of the United States. Because Crispus Attucks may also have had Wampanoag Indian ancestors, his story also holds special significance for many Native Americans.

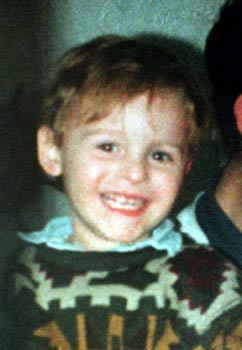

James Bulger was the victim of abduction and murder. His killers were two 10-year-old boys, Jon Venables and Robert Thompson. The murder took place in Merseyside, England. James disappeared from the New Strand Shopping Centre, where he had been with his mother Denise, on 12 February 1993 and his mutilated body was found on a railway line at Bootle on 14 February. As the circumstances surrounding the death became clear, tabloid newspapers compared the killers with Myra Hindley and Ian Brady who had committed the Moors Murders during the 1960s. They denounced the people who had seen Bulger but not realized the trouble he was in. The railway embankment upon which his body had been discovered was flooded with hundreds of bunches of flowers.

Nathan Hale was an officer for the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. Widely considered America’s first spy, he volunteered for an intelligence-gathering mission, but was captured by the British. He is best remembered for his speech before being hanged following the Battle of Long Island, in which he reportedly said, “I only regret that I have but one life to give my country.” Hale has long been considered an American hero and, in 1985, he was officially designated the state hero of Connecticut.

This article is licensed under the GFDL because it contains quotations from Wikipedia.