Creepy

Creepy  Creepy

Creepy  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Top 10 Metamorphoses in Literature

Folklore is littered with humans who are transformed into animals, trees or objects (willingly or otherwise). Being transformed into ‘the other’ has been taken up in modern literature to allow for exploration of complex issues of identity. It has also been used to amusing ends. Here are ten of the most memorable human transformation in literature.

Lewis Carroll’s Alice books are amongst the most famous children’s books in the world. The story follows a young girl called Alice as she experiences the absurd, and often anarchic, world of Wonderland. Her learning to cope with the changing world is a clear metaphor for growing up. But the book also features a literal ‘growing up.’ When Alice first follows the White Rabbit into Wonderland she finds herself trapped in a hallway full of doors. All are locked but she finds a key, so small as to only fit a tiny door on the ground, and a bottle labelled ‘Drink me.’ She knows enough to check the label for the word poison before drinking the potion. She shrinks and becomes stranded on the floor, having left the key up on the table. It is now she finds a cake labelled ‘Eat me.’ This cake seems the remedy to her woes when she grows large enough to fetch the key. Unfortunately, she continues to grow and is now too large for any of the doors. Growing up can be awkward, indeed.

The woman of the poem, Lamia, is a mysterious person who has become trapped in the body of a snake. One day, while hunting for a Nymph he is romantically pursuing, the god Hermes happens on Lamia. In return for revealing the location of the nymph, Lamia begs to be made human again. Returned to her gorgeous human body, Lamia weds her beloved. Unfortunately, a wise man at the feast reveals Lamia’s true nature, and she is returned to the form of a serpent before dying. Her husband dies of his grief. All in all there have been better weddings. The poet does not reveal much about the characters in the poem, and the meaning of their actions is left for the reader to decide, but there are clear Christian resonances of a man being undone by a woman and a snake.

To quote a song; this is a “tale as old as time.” Well, not quite, but it does feature several archetypal themes. The story of a young woman who offers herself in place of her father to an inhuman beast is a familiar one, but the meaning of the story has changed over time. All versions feature a young prince transfigured into a monster, and his eventual return to humanity via the transformational power of love. In the earliest published form of the tale, the emphasis is on the need for the beast to return to his human form. Over time this message has shifted somewhat to also include the message that the heroine must learn to appreciate more than appearances. It should be noted that this trope of love equating to beauty was wittily subverted in Shrek, where true love joins both people in the ‘monstrous’ state of ogre hood.

Transformation allows us to step outside of ourselves so we may understand others better. In the books of T.H. White’s Once and Future King we see metamorphosis included in an organized educational programme. These books deal with the early years of King Arthur, here a squire named Wart. Merlyn takes the young boy in hand to prepare him for his future role as monarch. To do this he transforms Wart into various animals. Wart becomes by turns: a merlin, an ant, an owl, a goose and a badger. Each transformation comes with an adventure and a lesson. The most spectacular transformations in the book occur during a wizard battle between Merlyn and Madam Mim, where the magicians shape shift rapidly to outwit their opponent. In a radical transformation Merlyn becomes a deadly bacterium to kill his rival.

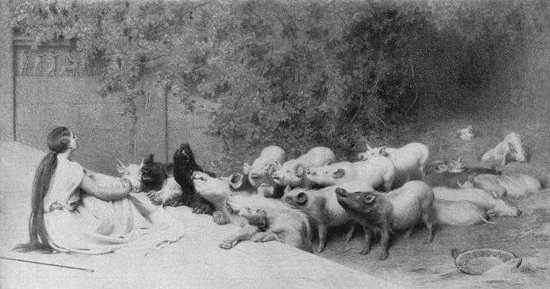

The Odyssey is one of the two epic poems ascribed to Homer, and tells the story of the return of the Greek soldiers who fought at Troy. Since the gods are displeased, none of the soldiers have an easy journey. Odysseus, in particular, will have to travel for ten years before allowed home to Ithaca and his wife. On the journey he meets with many strange adventures. On the island of Aeaea, Odysseus and his men meet the goddess of magic Circe. The beautiful Circe lures all the men to join her in a feast. The food is laced with her potions. After the men are sated she turns them into pigs. It is only the cleverness of Odysseus, and a warning from the god Hermes, which keeps him from falling for her porker plot. The men are restored and the journeys can continue (after a years interlude in which Odysseus beds Circe). Is this a simple fantastical tale, or is there a deeper meaning about the debasement of men who give in to baser urges? Homer was a good enough poet not to make his meaning explicit.

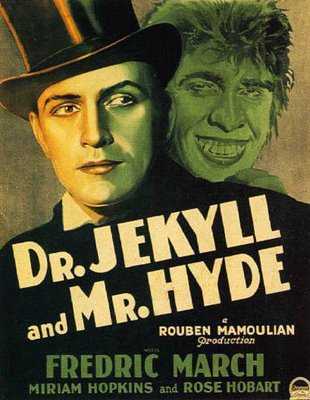

The concept of good and evil as forces in opposition to one another is an ancient one. The duality of good and evil has been internalized so that our own minds have become a battleground between devils and the better angels of our nature. The transformation which forms the basis of Stevenson’s book is more subtle than some others featured here. When Dr Jekyll takes a drug to separate his darker emotions from the good to make himself flawless, he succeeds only in creating an amoral creature, Mr. Hyde. At first Jekyll revels in the feeling of freedom Hyde gives him, but soon the violent Hyde commits murder and other terrible acts. The internal struggle between our animal instincts and higher reason is physically played out as the characters alternate. The transformation is marked by Jekyll becoming hideous as Hyde, though the disgust on seeing Hyde is more sensed than written in his face.

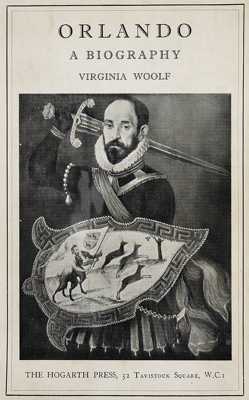

Transformation between sexes have a long literary tradition; in Greek legend the sightseer Tiresias was turned into a girl. The most important gender metamorphosis in all of literature is surely that of Orlando in Woolf’s story. In the book, a young boy is born during the Elizabethan period and through force of will he decides not to grow old. This conceit of will shaping reality gives Woolf the chance to examine English literature throughout history as her protagonist works on a poem over the course of centuries. The most famous event in the novel is the transformation of Orlando to Lady Orlando. The transformation occurs while Orlando sleeps and he wakes up as she. Now Woolf, one of the great feminist authors, has a chance to compare the male to the feminine as well as the idea of loves which are not bound by gender. The gender change does not upset or even greatly concern Orlando because the person inside the body is unchanged. Orlando is perhaps Woolf’s easiest work to read, but asks deep questions in an entertaining way.

Also known as the Metamorphosis, The Golden Ass is the only complete Roman novel to come down to us. Unlike some ancient works which seem remote, this book still amuses and interests readers today. The protagonist is a drifting young man, Lucius, just out of education. Deciding to travel rather than work, he visits his old home town and meets a witch whom he secretly watches transform into an owl. Deciding he wishes to fly he sneaks a drink of her potion. Instead of feathers he grows rough fur, and large ears. Lucius has transformed into a donkey. To turn back, he is informed, he must eat a rose. Unfortunately, fate intervenes and Lucius the Ass is stolen. Lucius is always on the verge of getting his rose but Apuleius never quite lets him eat it. Lucius learns the hard lot of a donkey and undergoes amusing, and risqué, adventures. In the end, Lucius is reborn in human form by the divine agency of the Goddess Isis, and dedicates his life to her service.

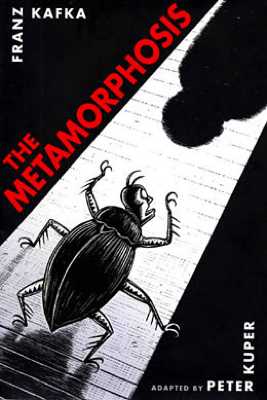

Kafka is the master of using the bizarre to explore the banality of existence. The Metamorphosis famously opens with the line, “One morning, when Gregor Samsa woke from troubled dreams, he found himself transformed in his bed into a horrible verminous insect.” Why Gregor has been changed is not addressed directly, and the novella deals more with how his relationships change than his new body. Gregor’s transformation does not affect his mind, and his character changes very little over the course of the story. The monstrous metamorphosis is contrasted with the other members of Gregor’s family, who transform themselves into a more capable group to deal with their shameful secret member. Gregor is killed when an apple thrown by his father gets lodged in his carapace and festers. The final metamorphosis for everyone is death.

Ovid is the source for most of our Graeco-Roman legends concerning transformations. His encyclopedic poem, The Metamorphoses, follows a narrative thread from the creation of the Earth to the transformation of Caesar into a god. The huge breadth of the stories Ovid tells ensured the popularity of the work even when Christian authorities frowned on the pagan content. Without Ovid we would have far fewer transformations to draw on. His telling of the story of Arachne is the fullest we possess. Arachne, a young lady puffed up with pride in her spinning ability, boasts that her fabrics are better even than Athena’s. Athena forces a contest between the two, to see whose work is better. When Arachne produces a magnificent tapestry, but with images of the sexual transgressions of the gods, Athena is so exasperated that she strikes Arachne. Arachne is spared death by the goddess but is shriveled, and her slender, skillful fingers changed to legs. Arachne the spider must learn to weave something more appropriate. With fifteen books of such stories Ovid is surely the king of metamorphoses.

Notable Omission: The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oscar Wilde; The Adventures of Pinnochio, Carlo Collodi