Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Top 10 Space Age Radiation Incidents

As if we don’t have enough terrestrial examples of potential exposure to accidental radioactivity release to worry about (Cherobyl, Fukushima, Three Mile Island) we also need to be looking up for other hazards. Throughout the history of US and Soviet space exploration, these countries have sent multiple devices into space (or attempted to send them into space) that were equipped with one type of radioactive material or another. Most were launched and performed successfully. Some, however, failed and, as a result, potentially exposed humans to radioactive material through fallout. Here are ten examples of space launches involving radioactive material that did not go as planned.

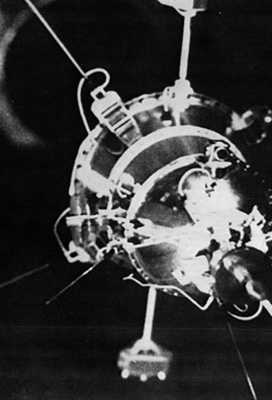

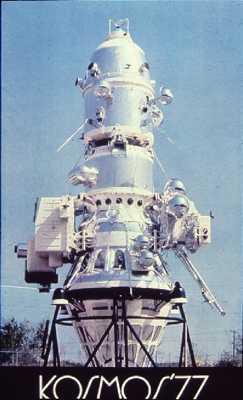

RORSAT, meaning Radar Ocean Reconnaissance Satellite, is the western term used to describe a series of Soviet Union satellites. These satellites were launched between 1967 and 1988, to monitor NATO and merchant vessels using radar. They were referred to as Cosmos satellites and carried type BES-5 nuclear reactors fueled by uranium-235. For the radar to work efficiently the satellites were placed into low Earth orbit. The plan was for the spacecraft to jettison the reactor into high Earth orbit when the satellites effective life had ended. However, there were several failures.

One such failure was Cosmos 1402. At the end of the satellites intended operational period, the reactor did not separate into high Earth orbit as planned. When the satellite reentered the atmosphere on February 7, 1983, the reactor was the last piece to come home to Earth. It landed somewhere in the South Atlantic Ocean.

The US equivalent to a Soviet Union satellite equipped with a nuclear reactor is the radioisotope thermoelectric generator or RTG. An RTG is a nuclear reactor type electrical generator. The heat released from the radioactive decay of a specified radioactive element in the device is converted into electricity and used for power. Thus, RTGs can be considered as a type of battery, and have been used as power sources in satellites, space probes and other unmanned remote facilities (such as a series of lighthouses built by the former Soviet Union inside the Arctic Circle). RTGs are used where solar cells are not practical and power usage is longer than that which can be provided by fuel cells. A common application of RTGs is as power sources on spacecraft such as Voyager 1, Voyager 2 and Galileo. In addition, RTGs were used to power scientific experiments left on the Moon by the crews of Apollo 12 through 17 (except Apollo 13, as we will see).

RTGs may pose a risk of radioactive contamination: if the container holding the fuel leaks, the radioactive material may contaminate the environment. For spacecraft, the main concern is that if an accident were to occur during launch or a subsequent passage of a spacecraft close to Earth.

One such incident took place on April 21, 1964, when a Transit-5BN-3 navigation satellite failed to reach orbit when launched. The spacecraft burned up over Madagascar and the plutonium fuel in the RTG was injected into the atmosphere over the Southern Atlantic Ocean. Traces of the Plutonium were detected in the atmosphere as a result.

On April 25, 1973, the Soviet Union attempted to launch one of its RORSAT satellites into orbit. However, the launch failed and the on board nuclear reactor plunged into the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Japan. Little else is known about this launch except that the USA is reported to have detected radioactivity over the region through air sampling.

The second incident involving a US RTG happened on May 21, 1968, when a Nimbus B-1 weather satellite exploded when the launch vehicle had to be intentionally destroyed and the lift off aborted shortly after launch. This satellite was launched from the Vandenberg Air Force Base. The remains of the satellite and the RTG plunged into the Pacific Ocean off California and, five months later, the RTG and its plutonium dioxide were recovered from the bottom of the Santa Barbara Channel. No radioactive material had been released.

Cosmos 367 was a Soviet RORSAT nuclear-powered satellite launched from the Baikonur cosmodrome. On October 3, 1970, only 110 hours after launch, the satellite failed and had to be moved to a higher orbit. Little else is known about Cosmos 367. It now orbits the Earth at an altitude of 579 miles, and circles the Earth at a speed of 4.4 miles per second. For a really cool real-time satellite tracking, look at where Cosmos 367 is here (those with low internet speeds be warned).

On December 12, 1987, the Soviet Union launched Cosmos 1900, another RORSAT nuclear-powered satellite. By May of 1988, communication had been lost with the satellite and the Soviets told the world it expected the satellite to renter the Earth’s orbit sometime in September or October of 1988. On or about September 30, 1988, just before the satellite reentered Earth’s atmosphere and burned up, the Soviets shot the reactor core out of the satellite, intended for high Earth orbit. However, the primary booster failed. Fortunately, the backup booster did move the reactor core closer to high Earth orbit, but 50 miles below its intended altitude. The reactor core is still in low Earth orbit and decreases in altitude with each passing year. Someday, it will come down to Earth, somewhere. The Cosmos 1900 reactor core now circles the Earth at an altitude of about 454 miles and speeds along at 16,753 mph. It takes just about 99 minutes to complete one full orbit. Go here if you would like to see its orbit, but for those with slow internet speed, be careful as this is a link to a website.

SNAP-10A was the first, and so far only, known launch of a U.S. nuclear reactor into space (although many radioisotope thermoelectric generators have also been launched). The Systems Nuclear Auxiliary Power Program (SNAP) reactor was developed under the SNAPSHOT program overseen by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission.

SNAP-10A was launched from Vandenberg AFB by an ATLAS Agena D rocket, on April 3, 1965, into a low Earth orbit over the Polar Regions. On board was a nuclear electrical source (a nuclear reactor) capable of producing 500 watts of power for up to a year. After only 43 days, an on-board voltage regulator failed, causing the reactor core to be shut down. The reactor is now stuck in a 700-nautical-mile earth orbit where it will stay for an expected duration of 4,000 years.

Making matters worse, in November 1979, an event caused the vehicle to begin shedding pieces. Therefore, a collision has not been ruled out and radioactive debris may have been released.

One of the better known incidents involved the unplanned reentry into Earth’s atmosphere of the Cosmos 954 satellite, on January 24, 1978. Partly, this was because, unlike the other reentries, the reactor and radioactivity reentered over land, not the ocean. Soon after Cosmos 954 was launched, it became apparent to US officials that the satellite had not achieved a stable orbit and, in fact, the orbit was decaying – fast. Once it was known that this was a Cosmos satellite and, therefore, there was a nuclear reactor on board, the US went into high alert status, tracking the satellite and trying to calculate when and where it would reenter the Earth’s atmosphere and crash (the reactor itself was too large to completely burn up on reentry and was sure to hit the Earth). When the satellite finally came down it did so over sparsely populated Northwest Territories of Canada. The radioactive material was spread over 124,000 square kilometers (47,876 square miles), most of which was recovered by a special and secret US radioactive emergency response team. However, it is possible the reactor core itself is still buried deep below the Arctic permafrost and remains radioactive to this date. Had the satellite made one more orbit, it would have reentered somewhere over the populated East Coast of the USA.

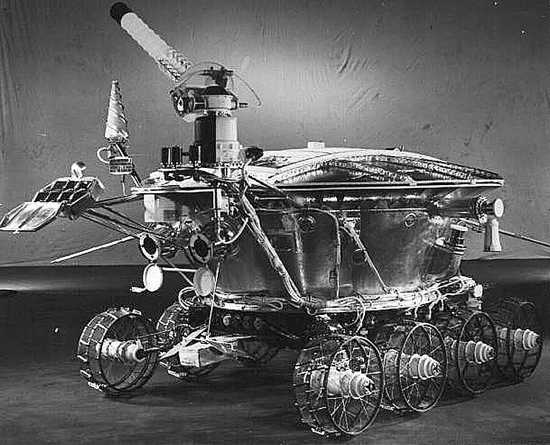

Unknown to many Americans, the Soviet Union was attempting, in secret, to put unmanned rovers onto the moon at the same time the US and Neil Armstrong were landing and walking on the moon. The Lunokhod program was a series of Soviet robotic lunar rovers that were to land on the moon between 1969 and 1977. If not for an accident during the launch, the Soviets would have been on the moon months before the Americans landed. On February 19, 1969, the first Lunokhod rovers were launched. Within a few seconds, the rocket exploded and the rovers were destroyed. On board the rovers were the Cosmos-type nuclear reactors to be used for power. When the rocket exploded, radioactivity was spread over a large area of Russia.

On November 10, 1970, the Soviets were successful when the second Lunokhod vehicle landed on the moon and became the first remote-controlled robotic rover to ever land on another planet or moon. In 2010, the Lunar Reconnaissance orbiter took detailed images of the lunar surface and detected the tracks left behind by the Lunakhod vehicle. Only then, forty years after it touched down on the moon surface, were scientists finally able to determine the final location of the vehicle.

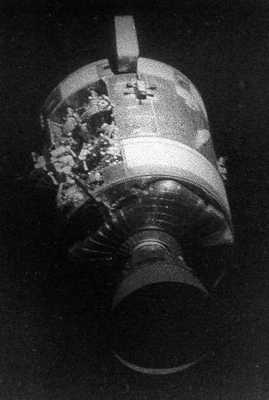

The heroic rescue of the astronauts of the failed moon mission Apollo 13 is well-known. On April 14, 1970 (1970 sure was a bad year for launching stuff into space), on the way to the moon, one of the oxygen tanks exploded, damaging the vehicle. The astronauts, James A. Lovell, John L. “Jack” Swigert and Fred W. Haise were able to circle the moon on April 15, and return safely to Earth on April 17, thanks to their own heroic efforts and those of engineers and scientists back on Earth.

The return to Earth, however, was not intended to take place with the Lunar module still totting the SNAP 27 radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG). This was designed to be left behind on the moon surface to conduct ongoing scientific experiments. As the Lunar module never landed on the moon, the SNAP 27 and its radioactive RTG came back to Earth along with the Apollo 13 astronauts.

The lunar module burned up in Earth’s atmosphere on April 17, 1970. It was aimed in the direction of the Pacific Ocean near the Tonga Trench (a 5 mile deep ocean valley) to minimize the potential exposure to radioactivity. As it was designed to do, the RTG and its 3.9 kilograms of radioactive plutonium dioxide survived reentry and plunged into the Tonga Trench. There, it will remain radioactive for the next 2,000 years. Subsequent water testing has shown the RTG is not leaking radioactivity into the ocean.

One unexpected benefit of the Apollo 13 mission was the survival, in an intact condition, of the RTG. The high reentry velocities the Apollo 13 RTG were exposed to demonstrate that the design is sturdy and highly safe.