The Arts

The Arts  The Arts

The Arts  History

History History’s Ten Most Lopsided Battles Ever

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

The Arts

The Arts 10 Iconic Masterpieces Attacked by Pure Pettiness

History

History History’s Ten Most Lopsided Battles Ever

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Top 10 Works Written in Prison

Prison literature is a fully formed genre. While locked up many people find the reflexive outlet of writing a way to pass the monotony. Others find that they feel they must write to express some wrong, either against themselves or others. While imprisonment has been the cause of great works, such as The Gulag Archipelago of Solzhenitsyn, this list will focus on those works actually composed within prisons or jails. There is no particular order to this list as each work will speak to different people in particular ways.

“Stone walls do not a prison make,

Nor iron bars a cage;”

These are the much quoted first lines of the final stanza of Richard Lovelace’s poem ‘To Althea, from prison.’ Richard Lovelace was one of the dashing young cavalier’s of the English civil war and is classed with the metaphysical poets. Sent to prison for presenting a royalist petition in support of pro-royalist bishops he used the time to compose this, his most famous poem. Written to, a possibly fictional, lover the poem expresses a theme common to much of the literature composed in jail; you cannot imprison the human mind. Despite the walls around him he can imagine his beloved and so he ends the poem with the lines-

“If I have freedom in my love

And in my soul am free,

Angels alone, that soar above,

Enjoy such liberty.”

While Lovelace found love set him free it was, for Wilde, love which led to confinement. After a serious of trials relating to his relationships with Lord Alfred Douglas and other men Wilde was sentenced to two years hard labor for gross indecency. While held in prison in Reading Wilde composed a long letter to Douglas which was later published posthumously as De Profundis. The work starts with an account of Wilde and Douglas’ relationship and how damaging it has been to Wilde. The tone is not accusatory but self-revelatory. The letter then turns towards the realizations that prison has forced on Wilde. Wilde ends with his plans for the future for, though we know his life would be cut short, he has learned-

“I have grown tired of the articulate utterances of men and things. The Mystical in Art, the Mystical in Life, the Mystical in Nature this is what I am looking for. It is absolutely necessary for me to find it somewhere.”

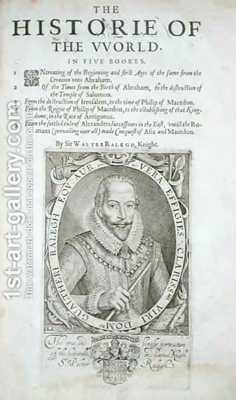

“Whosoever, in writing a modern history, shall follow truth too near the heels, it may haply strike out his teeth.”

Raleigh, we may take it from the statement above, would not be welcomed by academic historians today but his unfinished history of the world is a masterpiece. Raleigh traces the history of the world from creation to the third Macedonian war in 168BC. The book serves to show how again how a man’s mind, though his body is held captive, can travel over time and space. Raleigh never finished his history though he was released, and was later beheaded. His history includes this meditation on death.

“O eloquent, just and mighty death… thou hast drawn together all the far stretching greatness, all the pride, cruelty, and ambition of man, and covered it all over with these two narrow words Hic Jacet [Here Lies].”

“What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence.”

It is tempting to do just that with the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. It is undoubtedly one of the most influential philosophical works of the 20th century, and so is well deserving of a place on this list. It is also undoubtedly a work which requires multiple readings to start to come to grips with. Wittgenstein started makes notes for the Tractatus while a soldier in the First World War. He completed it while held prisoner by the Allies at the end of the war. Part of the difficulty in reading the Tractatus is Wittgenstein’s style; he uses short declarations and sub-clauses to state his views, with very little in the way of argument.

Marco Polo left Italy with his father and uncle in 1271 and returned in 1295. In those years of travel Polo traveled to the then poorly understood Far East. On Polo’s return to Italy he was captured by the Genoese and held captive. While in prison he related his adventures to fellow prisoner Rusticello de Pisa. Rustichello wrote down what he heard and soon copies of the tale spread throughout Europe. For centuries the Travels of Marco Polo were the best information the West had about China. While Polo’s account can be questioned in some aspects of veracity it has certainly proved influential. Contact with China had existed (certainly in trade in the days of ancient Rome) before Polo but with the dissemination of his book fascination with the ‘exotic East’ was born. Other Europeans had travelled to China before Polo but none left as detailed an account, perhaps a jail term to write would have secured them a place on this list.

“Mere waiting and looking on is not Christian behavior. The Christian is called to sympathy and action, not in the first place by his own sufferings, but by the sufferings of his brethren, for whose sake Christ suffered.”

Bonhoeffer had the many chances to lead an easy life. He was born into middle-class comfort in 1906 Germany. He might have followed his father in medicine or pursued music. Instead Bonhoeffer studied theology and did pastoral work in Harlem to become a pastor. When the Nazis took political power they also forced cooperative into positions of power. Bonhoeffer and other liberal churchmen form their own communion. He had many chances to move abroad and avoid persecution but, after intense internal debate, he chose to be in Germany for the duration of the war. Bonhoeffer was arrested in 1943 and held until just 23 days before the end of the war, when he was hanged. During his imprisonment Bonhoeffer wrote widely and this collection of his letter and papers contains much that is worth studying even if the finer details of Christian theology are not your cup of tea.

“My Dear Fellow Clergymen:

While confined here in the Birmingham city jail, I came across your recent statement calling my present activities “unwise and untimely.” Seldom do I pause to answer criticism of my work and ideas…”

We can be glad that King did pause to answer his critics because the letter he wrote from jail, where he was held for protesting without a permit, is a ringing vindication of the rights of all people. Bonhoeffer, as a profound theologian, can sometimes speak in terms whose meaning eludes us. This letter talks to everyone; Christian or not. King’s letter was written in response to eight local clergymen who published a letter, A Call for Unity, which called for African-Americans to press their case for equal rights through the courts and not by demonstrations. Dr King responds calmly and, in a fairly brief space, sets out all the reasons that it is impossible for a man of conscience to allow injustice to continue. This is the best document for understanding the greatness of King’s leadership. If I were subjugated by such injustice would I be able to meet it with such reason, determination, and forgiveness? But it is not just a call to those suffering discrimination personally, we must all be responsible for guaranteeing the rights of others.

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

“I therefore, a prisoner for the Lord, urge you to walk in a manner worthy of the calling to which you have been called, with all humility and gentleness, with patience, bearing with one another in love, eager to maintain the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace.”

Paul was the first, and most influential, Christian theologian. He started out as a persecutor of Christians but, after an encounter with Jesus on the road to Damascus, Paul became one of the most vocal supporters of Christianity. His letters proved so important to Christian theology that they were incorporated into the canon of the New Testament. While Paul was spreading faith in Jesus as the messiah he caused much consternation. After a confrontation in Jerusalem Paul was arrested and held in prison. Here he wrote several important letters to Christian communities – The Colossians, the Ephesians, the Philpians and one letter to Philemon. There is some scholarly debate over whether Ephesians and Colossians are genuine Pauline epistles but are still held by most Christians as part of the canon. Paul’s letters were later closely read by Martin Luther and Pauline theology was a major driving force behind the Catholic/Protestant schism.

“Whoso pulleth out this sword of this stone and anvil, is right wise King born of all England.”

England has a rich history of Arthurian mythology which has inspired writers for hundreds of years. While imprisoned Thomas Malory wrote, using French sources, the most famous version of Arthurian legend. We are not entirely sure of the biography of Malory, there are several competing candidates for the identity of the author, but we know from the work itself that it was composed in prison. Le Morte d’Arthur has given the world some of the best known images of Arthur, such as the pulling of the sword from the stone and the Lady of the Lake, her arm covered in shimmering samite.

“While I was thus mutely pondering within myself, and recording my sorrowful complainings with my pen, it seemed to me that there appeared above my head a woman of a countenance exceeding venerable…”

When it comes to literary works composed in prison there is no choice but The Consolation of Philosophy for the first place, to my mind at least. Ever since it was published the work has been influential. Translated from Latin into English by King Alfred, Chaucer and Queen Elizabeth I, the book serves as a warning to those in power. Boethius was at the pinnacle of power in Rome after the collapse of the Western Empire. Unfortunately he fell foul of Theodoric the Great and was imprisoned. This sudden change in fortune is what prompted Boethius to write this philosophical dialogue between himself and the Goddess Philosophy. Boethius feels aggrieved that he has had everything taken away from him. Philosophy leads him by questioning to consider whether anything outside of himself was ever truly his to begin with. I’ll admit not everyone finds Philosophy’s words all that consolatory but it remains a foundational text for Western civilization.