Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Undeniable Signs That People’s Views of Mushrooms Are Changing

Animals

Animals 10 Strange Attempts to Smuggle Animals

Travel

Travel 10 Natural Rock Formations That Will Make You Do a Double Take

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Hidden in Your Favorite Movies

Our World

Our World 10 Science Facts That Will Change How You Look at the World

Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Incredible Female Comic Book Artists

Crime

Crime 10 Terrifying Serial Killers from Centuries Ago

Technology

Technology 10 Hilariously Over-Engineered Solutions to Simple Problems

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptions That Brought Popular Songs to Life

Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Undeniable Signs That People’s Views of Mushrooms Are Changing

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals 10 Strange Attempts to Smuggle Animals

Travel

Travel 10 Natural Rock Formations That Will Make You Do a Double Take

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Hidden in Your Favorite Movies

Our World

Our World 10 Science Facts That Will Change How You Look at the World

Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Incredible Female Comic Book Artists

Crime

Crime 10 Terrifying Serial Killers from Centuries Ago

Technology

Technology 10 Hilariously Over-Engineered Solutions to Simple Problems

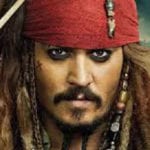

Top 10 Awesome Films Hollywood Ruined With Lies

To “hollywoodize” a film is to distort historical or scientific facts deliberately for the purpose of enhancing the drama – essentially, to wreck a film. Below are ten movies with great potential that, alas, in the hands of Hollywood, have de-educated the masses by their errors – simply for the sake of entertainment; much in the same way as some unnamed top 10 list sites do. Read on for an education in what not to do when making historic films.

This makes the list because of one particular scene, and anyone who has seen it knows what it is – the scene in which Jones escapes an atomic blast by hiding in a lead-lined refrigerator. George Lucas, who wrote most of the story, swears that he consulted nuclear physicists on the plausibility of the scenario and was assured it was feasible – namely, that the lead would halt the radiation. Assuming Jones did not break his neck in the tumbling, the odds of survival would be about 50-50.

That isn’t true, as any schoolboy will tell you. The radiation won’t penetrate, but the heat will, and it will cook anything inside the fridge faster and more efficiently than an oven. The tumbling might not have broken Jones’s neck, but it would certainly have broken bones; and if he then decided to leave the fridge, he would have melted – just like Toht, the Nazi torturer in Raiders of the Lost Ark. How’s that for full circle?

The film is not as good as the first three, but it seems like Old Spielberg had to get the rust off and remember what Young Spielberg was like. If they make a 5th one, it will probably be better.

No surprise here, at least on the surface. Aliens have invaded Earth – but don’t count on Will Smith, Jeff Goldblum, and a suicidal Randy Quaid to save you. You might say this one was “inspired by” “The War of the Worlds”, but no credit is given to H. G. Wells. The aliens are defeated by force, not by incidental viral infections. It’s so similar to Wells’s story that Steven Spielberg, who had plans to remake The War of the Worlds even in 1994, chose to wait a few more years. It’s a destroy-the-world movie, something for which director Roland Emmerich – who lands another spot on this list – is well-known.

Nevertheless, willful suspension of disbelief can only be stretched so far. The aliens, as always, have some sort of protective forcefield around all their ships, from the mothership in orbit to the individual planes. Their technology has to be defeated first, and that falls to the egghead Goldblum, who gets the idea to upload a computer virus into the mothership’s computer banks to destroy its computerized forcefield. Off they go into the wild blue yonder, sneaking aboard in the spacecraft that crashed near Roswell, New Mexico in 1947. Goldblum uses a Macintosh operating system from 1993, to communicate with the aliens’ computer technology. That’s right – no compatibility problems. “It Just Works”.

This is not to mention the fact that the mothership, an object with one-quarter the mass of the Moon, sits in orbit throughout the film. If it did so in reality, it would cause tidal waves that submerged all port cities in the entire world, including London, Tokyo, New York City, Boston, and Wellington, New Zealand – destroying our beloved Listverse which is situated there.

1984

This one proves the real danger of hollywoodizing a story: creating misconceptions about a historical person. Antonio Salieri is well known to have loathed Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, because Mozart was an uncouth misfit, a perpetually sexual-minded pervert with a particular penchant for poop humor (more on that in about six hours when the second of today’s lists is published). But Salieri had absolutely nothing to do with poisoning one of humanity’s greatest geniuses. He loved Mozart’s music, and would never have put an end to it.

The film depicts him as a mysterious man in a black mask who commissions Mozart’s Requiem, which he intends to call his own after poisoning Mozart to death. Salieri did no such thing. That masked man is actually known: Count Franz von Walsegg, who wanted the Requiem for his dead wife. The film also shows Mozart being buried in a pauper’s grave, ostensibly because he was so poor that he could not afford a headstone. This is not true. All Vienna citizens were buried in mass graves at the time per an order from Emperor Joseph II, to combat disease. Mozart’s death has been blamed on over three dozen illnesses, natural and man-made. Most likely, we will never know what actually happened to him.

This film was inspired by the book “The Coming Global Superstorm”, by Art Bell (that should start ringing some bells already) and Whitley Strieber. The phrase “inspired by” is used when too few elements remain true to the source material to use the phrase “loosely based on.” The entire film is designed to warn people about the dangers of global warming. Whether or not global warming is taking place, the extremely sudden arrival of the storm in the film is absolutely impossible. It cannot happen that way.

The film depicts freak storms all over the world, including tornadoes in Los Angeles and 3 solid days of inundating rain in New York City, all of which lead, in only days, to three gigantic, cyclonic supercells, one centered over North America, one over Western Europe, and one over Russia, which turn from rain to snow and drive everyone out of the Northern Hemisphere. Americans have to take refuge in “third world countries.” The book explains that this could happen over the course of 10 years. The film depicts it taking place in 4 or 5 days. Antarctica could completely melt in 1 hour – and still not cause such storms in such a short period of time. We should try to stop burning up all our fossil fuels, of course; but you don’t need to fear instantaneous, worldwide blizzards.

This film is one of the least accurate in the history of historical films. It was a vehicle for Errol Flynn, fresh off his fame as Robin Hood, and depicts General George A. Custer as the hero of his last stand. Custer was no hero, no role model, as history clarifies. He is depicted as respecting the Sioux Indians, and attempting to save them from taking the blame. The real Custer totally hated them, and adored the glory of raiding their camps, pursuing their armies, and cutting down as many as he could. This is why they took no prisoners at the Little Bighorn.

He and Crazy Horse never actually met, but they do in the film, and Crazy Horse fires the shot that kills him. The 7th Cavalry charges into the battle with swords drawn, but in reality they did not have their sabers with them when it happened. Had they, they would still have lost – but would have taken a lot more Indians with them. Philip Sheridan is depicted as commandant of West Point when Custer graduates, but he never held this post and was actually only 9 years older than Custer. Sheridan is a colonel in the Civil War scenes, but was really only a first lieutenant when the Civil War began.

This lister, heretically, does not much care for this film. Sure, it was good the first time . . . but it doesn’t have enough depth for repeat viewings. The technical errors are too many and major to allow for good drama, but then, most of them are based on Stephen King’s novella, in which the same errors are made.

Most deplorable is the fact that Brooks Hatlen is forced to take his parole: unable to rejoin society, he hangs himself. This is patently false. No American prison, ever during the 20th and 21st Centuries, has forced a convict to leave on parole if that convict does not want to leave. They are welcome to stay as long as they want, and after 50 years of incarceration, about 46% do.

Andy Dufresne’s escape is riddled with plot-holes. He spends 19 years tunneling through his cell wall into a utility area between blocks. No prisoner is ever kept in the same cell for more than a few months, precisely to prevent him or her from doing this.

Andy worms his way 500 yards through a sewer pipe to freedom. But sewer pipes are not wide enough for a man to fit in. Most need be no wider than about 10 inches. Even in 1966, when the escape takes place, sewer pipes did not empty raw sewage directly into the environment. Andy would have found his way into a septic tank or sewage treatment plant and drowned. But the instant he entered the pipe, he would have suffocated: there is no oxygen in sewer pipes, only methane and nitrogen.

This film brought loads of tourism to Scotland, revived Mel Gibson’s career, and raised him to the A-list of directors. It is based on only one source: an epic poem by Blind Harry, a Scottish poet of the 1400s, some 200 years after William Wallace lived. A single source can be very unreliable, not in the least because a Scottish author may be pro-Scottish, anti-English, and embellish the exploits of the main character.

The film depicts the Battle of Stirling Bridge as occurring not on a bridge but in a vast, green field, with plenty of room for the armies to maneuver. The English armored knights would not have charged their horses directly into the front of the Scottish army, precisely to avoid running into pikes. They would have flanked on both sides if they had the room. But the real battle took place on a narrow stone bridge that still spans Stirling River, and this is why the English knights had to charge straight into the Scottish front. The Scots did keep their pikes out of sight until the last second to fool the horses – horses won’t run into pikes if they have time to stop.

The Battle of Falkirk is depicted as more of the same, which is not true. The Scots set up their infantry in schiltrons, which are outward facing circles of pikes. This was to prevent the English knights from flanking, since there was no river or bridge to hem them in. Meanwhile, the Scottish archers were supposed to duel the English archers, and the two cavalries would flank into each other. The Scottish cavalry commanders were not bought off by King Edward I. They simply got scared and fled with their horsemen. Then, the English cavalry routed the Scottish archers, and the English archers pounded the schiltrons until they charged the English infantry pell mell and were cut down.

The French princess, Isabella, was 7 years old when Wallace was executed. They did not have any sexual liaison, and no child who would have taken the throne from Edward II on his father’s death. The Battle of Bannockburn is implied as immediately after Wallace’s execution, but it took place 9 years later in 1314. Most damning of all, Robert Bruce is depicted as a sometime-traitor, who takes the field at Falkirk as an English knight. Robert Bruce did no such thing, and was just as formidable a fighter as Wallace. And though it wouldn’t be much of a Scottish film without kilts, the Scots did not start wearing them until the 1500s.

In addition to its producers’ and director’s atrocious mistreatment and killing of horses, this film is loaded with deliberate and ridiculous lies. The climactic charge is depicted as revenge by Errol Flynn’s character on the Indian forces of Surat Khan, allied with the Russians, who massacre hundreds of British soldiers early in the film. Surat Khan’s character was actually invented for the film, and the only massacre of British forces to which this scene could be an allusion is that of Elphinstone’s Army, in 1842 outside Kabul, Afghanistan. The real charge was a result of miscommunication between two British officers.

Worst of all, the film states that the charge was successful in routing the Russians and breaking the Siege of Sevastopol. This isn’t true. The charge was an utter, humiliating failure for Britain. The Russians were not driven away, and Sevastopol was not taken until a year later. The film even dates the charge incorrectly, listing 1856. The charge took place on 25 October 1854.

This film routinely appears on such lists, because it Americanizes an event America had precisely nothing to do with. In the film, an American submarine is sent on a mission to find the crippled German U-boat 571, which carries the top secret Enigma coding machine. The Americans take out the Germans, steal the Enigma, and sink a second sub as well as a destroyer. What’s wrong with this picture?

The British are the ones who raided a submarine and captured the first Enigma machine. The U-boat they raided was U-110, on 9 May 1941. There was a real U-571, but it had nothing to do with the events depicted in the film and was never captured. After the American crew, led by Matthew McConaughey, seize the Enigma and sink an enemy U-boat, they duel with a German destroyer. German destroyers were extraordinarily rare in the Atlantic.

This film infuriated Great Britain and was eventually criticized by Prime Minister, Tony Blair, himself, drawing something almost like an apology from Bill Clinton. The credits mention various missions that succeeded in stealing Enigma machines, almost all by the British.

Perennially hailed as one of John Ford’s utmost masterpieces, its cinematography is among the finest in cinematic history. But that’s about all that may be fairly said in favor of it. If you know your history of the events surrounding the Gunfight at the OK Corral, you will shake your head throughout the film.

The events took place in 1881. James Earp, the youngest of the Earp Brothers, is shown killed after a cattle rustling, but James died in 1926 of natural causes. The title refers to a woman named Clementine Carter, who never existed. She is based, more or less, on Big Nose Kate and Josephine Earp. The former was Doc Holliday’s lover, the latter Wyatt Earp’s second wife.

Doc Holliday, played by Victor Mature, is depicted as the only doctor of any kind in the entire town, and though merely a dentist, he is required to perform major surgery. No town with a population as large as that of Tombstone, Arizona, would have relied on a single dentist for all gunshot-wound related needs. Tombstone had a full-time surgeon, and in reality Holliday had long since given up his dental practice. He is also killed in the gunfight; but the real Holliday actually died of tuberculosis 6 years later in Colorado. Victor Mature does not exactly look tubercular. Historically, everything is wrong with this one.