Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

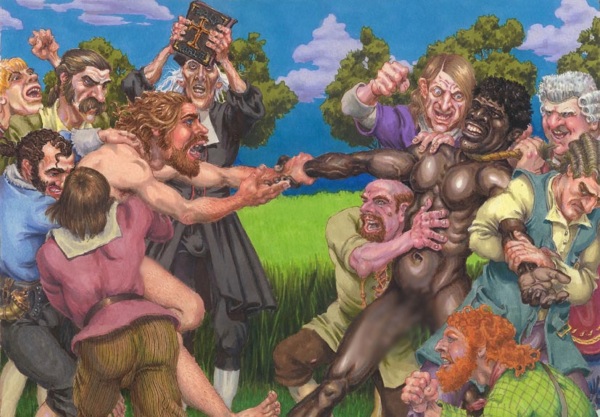

10 Lesser-Known Events in American History

Many historic events that are common knowledge at the time they occurred might be forgotten by some citizens of the twenty-first century—except history geeks like us and the occasional Jeopardy contestant. Here are ten lesser known incidents which happened in pre-twentieth century American history that you probably weren’t taught in school.

Nope, this isn’t a speculative history scenario and Nazis don’t come into it. In 1842, a society was established in Germany, the Verein zum Schutze deutscher Einwanderer in Texas—the Society for the Protection of German Immigrants in Texas, or the Adelsverein. The goal was to organize a mass immigration movement to colonize the Republic of Texas, thereby creating a new German state in the heart of America. By 1847, over 5,000 German immigrants had made their way to Texas and established five settlements. Another 2,000 immigrants arrived by 1853. However, the New Germany didn’t happen, mainly through a lack of business sense, mistrust among the members, and losses through land speculation.

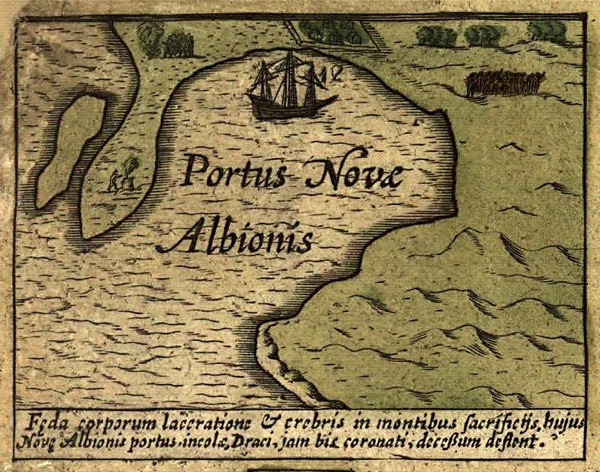

Sir Francis Drake, the English sea captain and explorer under Queen Elizabeth I, claimed an area of land on the west coast of North America in 1579. His claim was valid by sixteenth century standards. He had obtained consent from local natives, and he was the first European to discover the place, but as it turned out, the Crown wasn’t much interested in the Pacific side of the New World. By the time the twentieth century rolled around, the event had been mainly forgotten and achieved legendary status among historians until 1936, when the discovery of an artifact in San Francisco Bay proved Drake’s visit and the British claim on California, or New Albion. By the way, in October 2012, the US government designated a site on the Point Reyes Peninsula as Drake’s landing place and a historic landmark.

Francis Scott Key penned the lyrics to America’s favorite theme song, there’s no doubt about that, but the music—that impossible to sing, soaring, bombastic anthem that has made generations of baseball games hideous with off-key renderings—was written by John Stafford Smith, an Englishman. Around 1780, he composed the melody of a drinking song, To Anacreon in Heaven, with lyrics by Ralph Tomlinson. Not exactly Party Rock, the song contains classical references to Venus and Bacchus. While pretty hot stuff back then, it isn’t all that racy to modern ears. Doing what everybody did at the time, Key recycled the music in 1814 to go along with his famous verses about the bombardment of Fort McHenry.

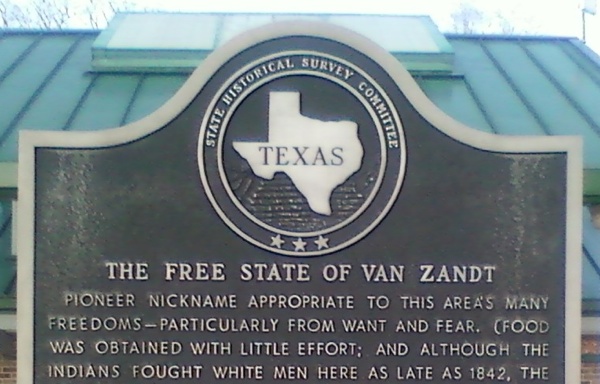

Van Zandt County in east Texas was once called the Free State of Van Zandt, an independent state once in conflict with the United States. Following the Civil War, federal troops were stationed in many Texas towns. Fed up with martial law, the citizens of Van Zandt voted to secede not just from Texas, but from the United States as well. The government wasn’t going to stand for any shenanigans, so US Army soldiers led by General Sheridan were sent to put down the uprising. Fortunately, the Van Zandt army had celebrated their new freedom a little too heartily and the drunks were rounded up without too much fuss. Later, many of the men escaped custody. Seceding from the US was no longer in the cards, though the resolution made by the county to separate was never formally withdrawn.

Heard of the famous “Shot Heard Round the World?” Well, the Revolutionary War nearly started early thanks to Sarah Tarrant, a nurse with a fiery temper who lived in Salem, Massachusetts in 1775. British commander Alexander Leslie came to Salem in search of cannons he believed were hidden there by rebels. Upon his arrival, some of the younger citizens taunted him, refused to let his troops cross the bridge into town, and scuttled his boat. Worse, the Salem militia gathered, armed and ready. Nevertheless, Leslie persisted. To save face, he eventually marched his men into Salem and turned them around to return to Boston. On their way out, Sarah Tarrant hurled insults at the retreating redcoats, one of whom stopped and aimed his musket at her despite Leslie’s order to stand down. Fortunately, the soldier didn’t fire, otherwise it’s possible the Revolutionary War would have started then and there.

Do you know why every school kid in America knows about Paul Revere’s famous midnight ride? Because Revere rhymes with a lot more words than Ludington. Not to say Revere didn’t ride to warn his fellow Americans that British troops were on the way, but so did other little known heroes like Sybil Ludington, the sixteen year old daughter of a captain in the New York militia. In 1777, when British troops attacked Danbury, Captain Ludington began putting his militia in order. He sent Sybil to rouse the countryside and sound an alarm. She rode forty miles through the dark, rainy night, stopping at farmhouses along the way to wake up the sleeping inhabitants. Not only did she have to elude British troops in the area, but also loyalists to the Crown, and robbers. She succeeded and returned home a local heroine.

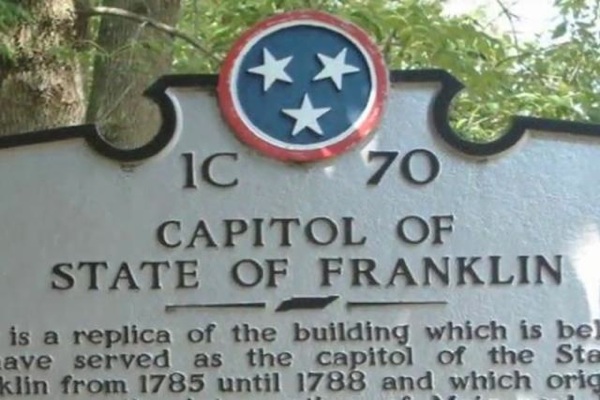

To the thirteen states existing after the Revolutionary War, we must add a fourteenth: the state of Franklin, named in honor of Benjamin Franklin. In 1784, the citizens of the region decided they’d have better luck living on their own rather than as part of North Carolina or as territory of the federal government. They subsequently voted to secede from North Carolina, but Congress refused to let Franklin join the Union. The independent republic kept chugging along for four years, writing its own constitution, making deals with Native American tribes, and even attempting to negotiate a treaty with Spain. The last act proved too hard to swallow. North Carolina swiftly arrested the governor, John Sevier. Franklin gradually lost its purpose and became part of the newly formed state of Tennessee in 1796.

Many US vice presidents have to take a back seat to the POTUS in the public’s consciousness, but here’s a V.P. who stands out for his unusual accomplishment. Before he got into banking, politics, and ultimately became Calvin Coolidge’s vice president in 1925, Dawes liked to play the piano and compose music. He co-wrote a classical ditty for violin and orchestra in 1911, Melody in A Majoror Dawes Melody. In 1951, songwriter Carl Sigman added lyrics and changed the name to It’s All in the Game. Performed by Tommy Edwards in 1958, the song spent six weeks at number one on the pop chart and has since been covered by Cliff Richard, Nat “King” Cole, Isaac Hayes, Barry Manilow, and other artists.

In 1647, when Manhattan was a Dutch colony called New Amsterdam, a married barber-surgeon, commissary of stores, and respected explorer named Harmen Meyndertsz van den Bogaert was caught in flagrante with another man—a black slave. Sodomy was a capital offense according the strict Calvinist faith practiced by the Dutch at the time. Pursued by the authorities, Van den Bogaert broke out of custody in Fort Orange and fled with his lover to an Iroquois village, but was tracked down. In the ensuing struggle to capture him, a shoot-out occurred and a longhouse was set on fire. He was literally dragged away by the posse and returned to Fort Orange. He got out a second time, but drowned in the second escape attempt, possibly making him the first victim of homophobia in North America.

Not very long after the end of the Revolutionary War, some citizens of Massachusetts once again took up arms to defy an oppressive force—this time, the newly formed state government in Boston. In 1786, because of a severe economic crisis, farmers in Massachusetts began losing their farms. Some were jailed for debt. Petitions became mass protests by farmers and other citizens, which led to jail breaks, and finally a short-lived revolt under Daniel Shays. Their main acts of civil disobedience were blocking courts to prevent other debt laden farmers from being imprisoned By 1787, Governor Bowdoin’s forces put an end to the rebellion, but voters sympathetic to the rebels’ situation didn’t reelect him.