Creepy

Creepy  Creepy

Creepy  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

10 Seemingly Useless By-Products That Made Millions

For the longest time, when most companies produced a product, they were content with doing nothing about the waste leftover from the production process. Times have changed, though. Through genius innovation, many entrepreneurs have taken what was once useless sludge and transmuted it into massive profits.

After yielding their finished product, breweries in the late 19th century were left with thousands of pounds of excess yeast and frothy liquid leftover from the manufacturing process. It was common practice to dump it all down the drain, rendering it useless, but German scientist Justus Liebig desperately wanted to find a way to make it edible. Seeing the vast quantities of wasted product that he could attain for free, he accidentally discovered that the yeast could be concentrated, bottled, heavily salted, and then eaten. He called his product Marmite. It ended up being a massive success in countries like Sri Lanka and Britain, and it was a mainstay in the cost-efficient rations of soldiers in both world wars. To this day, the company still manufactures over 24 million jars a year and is so popular that it has created a competitive market with other companies, such as Vegemite.

The human race has a rich history of getting hopelessly inebriated, and with the demand for fermented, smashed grapes also comes the demand for agents to remove the bits of yeast, bacteria, and proteins that pollute the finished product. This process is called clarification. For thousands of years, our ancestors used things like oyster shells, chalk, and earthenware during this process, and even went so far as to store the wine in the dried skins of dead animals. At the end of the 18th century, commercial brewing was going through a massive expansion which led to the innovation and widespread use of Isinglass, a collagen obtained from the dried swim bladders of fish. You’d think by now we’d have some sort of machine to streamline the clarification process, but it turns out the bladders of fish do the job better than anything we can synthesize. They accelerate the process of clumping the live yeast together into a jelly-like substance through an electro-static interaction between the positively charged collagen molecules and the negatively charged yeast cells, creating a tight bond between yeast and Isinglass. The result is a cleaner and clearer wine in a fraction of the time.

When coal is carbonized to make high-carbon fuel or gasified to make coal gas, coal tar is produced as a byproduct. For a long time, uses for coal tar were sparse and exclusively industrial. It was mostly lit on fire and burned for its heat, if for no other reason than simply because it was flammable. In 1878, Constantin Fahlberg was part of a Johns Hopkins University study on coal tar where he experimented with a variety of different compounds throughout the day. One night, while eating bread at dinner, he noticed an incredibly sweet taste on his hand and instantly ran back to his laboratory and tasted all of the beakers he was working on that day. After several hours of searching, he found one in particular that was 300 times sweeter than sugar. Simply put, the world of zero-calorie artificial sweeteners was born. He named his creation Saccharin—a wildly popular alternative to sugar throughout the 20th century and the chief ingredient in Sweet N’ Low.

Cow intestines led a pretty depressing existence prior to the nineteenth century. Their taste was overshadowed by the rest of the delicious parts of the cow and their utility was overshadowed by the versatility of pig and sheep intestines for sausage casing. All of that ended in 1875 when Pierre Babolat made the first cow intestine tennis racket, citing its ability to absorb wrist strain and control the ball better. Typically, the 120-foot small intestine is extracted and cut into 40-foot strands that are then treated with chemicals to aid preservation. The strands are spun tightly together and dried out in a humid room for six weeks to prevent cracking. It takes nearly four whole intestines to make a single tennis racket, but even today it’s a commodity that’s cherished by some of the world’s best professional tennis players. Previously, cow farms would pay waste removal companies thousands of dollars each month to remove the leftover intestines, but now they’ve become one of the most profitable byproducts of the slaughtering process.

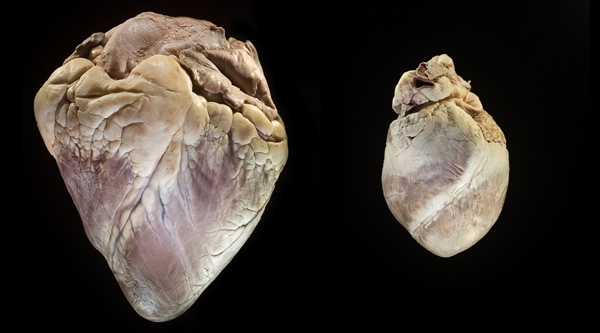

Throughout history, pig farmers rarely found much use at all for the pig’s heart. In fact, some internal organs had such little value, they would grind them up into a sludgy makeshift feedstock and feed it to pigs they would breed in the future. In 1968, the marginal success of experiments at the National Heart Hospital in London, England eventually led to the development of porcine heart valve replacement surgery. Today, there is an entire subculture of the pig farming community that breeds pigs exclusively for their heart valves and sells them to bioprosthesis companies. Nature Farm in Malta, Idaho, breeds over 200 sows a week, all meeting the strict specifications required by the porcine heart valve market. A typical heart valve will run consumers about $5,000 in the current market, and considering the typical American diet, pig hearts are probably better suited for us anyway.

For as long as horses have bred and domesticated, their urine has seeped into the topsoil, smelled terrible, and killed vegetation. Things changed in 1942 when the FDA approved Premarin, a hormone replacement therapy that’s derived from the urine of pregnant horses. It contains over 200 hormones that combine with modern medical advances to greatly reduce the effects of several ailments. Its use in hormone replacement therapy reduces hot flashes. Its estrogen is used to treat certain types of clinical depression. Its various hormones aid patients plagued by heart disease and osteoporosis, and it can even be used as a chief ingredient in fertility treatments. In just under sixty years, a yellow, alfalfa-smelling waste product has turned into a $2 billion industry that helps more than nine million people a year relieve symptoms of painful and annoying conditions.

During the life of a cow, hooves are a source of anguish for farmers because of their tendency to cause health problems and pain. In death, they used to be expensive to dispose of and relatively useless, but that changed in the mid 1900’s when it was discovered that their chief ingredient, keratin, could be added to fire extinguishers to aid in suppressing the high-heat, high-intensity fires triggered by aviation fuel. Keratin acts as a bonding agent to the foam bubbles that would typically break up upon contacting these remarkably hot fires, and the reinforced structure forms an oxygen-proof blanket that stifles the flames. Additionally, for the past decade or so, beauty companies have been selling ‘Brazilian Keratin Treatments’ that claim to use keratin to smooth and shine hair and ‘revitalize’ the outer layer of skin. Although some of the biggest players in the industry have moved to synthesized keratin, the majority of companies still get it from cow hooves, feathers, and sheep wool.

When corn and potato farmers are done harvesting their crop, a crushed, tattered remnant of the original stalk remains, seemingly useless. When the biomass movement began in the late 20th century, farmers began to extract the starch from the leftover plants by blasting them with water and then letting the white-ish liquid dry in the sun for a few days. They then took the residual powder and processed it into a pellet they referred to as resin. This resin is used—often times in coalition with several other waste products—to produce a plethora of fully biodegradable bioplastic products, including starch-based packing peanuts. In fact, there is so much starch content in some of these bioplastics that the human body can actually digest them! A vibrant global marketplace now exists and is growing tremendously. Just one company from California named Cereplast tripled their earnings in one year—from $1.5 million to $5.4 million.

Urea, in short, is the component of urine by which the kidneys expel excess nitrogen from the body. For years it was (literally) pissed away, but in 1828, the German chemist Friedrich Wohler found a way to isolate urea from the urine by treating silver isocyanate with ammonium chloride. Despite this breakthrough, urea continued to be of little use until the 21st century. In response to consumer demand for teeth-whitening products with a long shelf life, companies that sold whitening toothpaste and teeth whitening strips began using urea mixed with hydrogen peroxide, a substance called carbamide peroxide. The urea is used to stabilize and extend the shelf life of the whitening agent. It is primarily found in clinical grade whiteners that are found at a dentist’s office, but one particularly well known product that uses it is Colgate Simply White.

Twenty years ago, not only were chicken feet almost completely useless, chicken farmers had to pay to get rid of them. Most of the time, they would end up as a filler in dog foods. In the 1990s, globalization became a more feasible reality for smaller companies aspiring for a transnational business model, and chicken farmers started profiting from the sale of chicken feet to China. Now, the U.S. exports about 300,000 metric tons of chicken feet a year. Just one company, Perdue Farms, produces over a billion chicken paws a year and brings in more than $40 million in revenue. The demand for chicken feet is so high, the farmers could breed twice as many chickens as they do now and still easily sell them to China, but they would have no way to sell all the other parts of the chicken in the United States. What was once a complete waste product is now the chief profit center for every chicken farmer in the United States. It is the consensus amongst the industry that without the global demand for chicken paws, most farms would be driven out of business.