Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

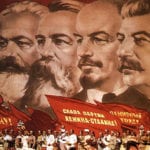

10 Biggest Secrets of the Soviet Union

Communist Russia was an exemplar of openness and accountability in government. That’s not a sentence you’ll read these days—at least not outside of North Korea. (Although I suppose you’re reading it now, which makes my statement a little void. Unless you’re actually in North Korea, in which case the point stands.) Anyway, what we’re getting at through subtle sarcasm is that the Soviets were actually really big on secrets—so here are ten of the most audacious.

If asked to name the worst nuclear disasters in history, pretty much every reader of this article would be able to come up with Chernobyl and Fukushima. Far fewer would know number three, the Kyshtym disaster of 1957, named for a town in the south of Russia. As with Chernobyl, the main cause of the disaster was really, really bad decision making—specifically, implementing a cooling system for nuclear waste that couldn’t be repaired. When the coolant for one tank at the nuclear plant began to leak, the operators simply switched it off and left it for a year. Really, though, who needs cooling systems in Siberia?

People with nuclear waste storage tanks, it turns out. The temperature in the tank rose to over 650 degrees Fahrenheit (350 degrees Celsius) eventually causing an explosion that threw the 160 ton concrete lid into the air—from its initial location, twenty-seven feet underground. The radioactive fallout spread over 7700 square miles (20,000 square kilometers)—more than the combined area of Connecticut and Rhode Island.

The homes of 11,000 people were demolished following evacuation of the area and 270,000 people were exposed to radioactivity from the site. It was 1976 when a Soviet emigrant first hinted at the disaster for the Western public. The CIA had known about the disaster since the sixties but—fearful of public backlash against America’s nuclear industry—downplayed the seriousness of accounts. It wasn’t until 1989, three years after Chernobyl, that details of the disaster became public.

In May 1961, US President John F. Kennedy announced that he believed the US should commit to landing a man on the moon by the end of the decade. Until that point, the Soviets had led space exploration, achieving the first object into orbit, the first animal into orbit, and the first man into space. Yet on 20 July 1969 Neil Armstrong became the first man on the moon, defeating the Soviets in that race. Except for the fact that the Soviets never officially took part—they denied ever having a manned lunar program until 1990. This was part of a larger policy of keeping every space program secret until it was successful.

The Soviets had been forced to make a partial admission almost a decade earlier in August 1981, when a Soviet satellite known as Kosmos 434, launched in 1971, was about to re-enter Earth’s atmosphere above Australia. The Australian government, concerned that nuclear materials might be on board, were assured by the USSR’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs that the satellite was an experimental lunar cabin.

Other aspects of the program, including test launches, were hidden. A trial of moon suits during a spacecraft link-up as late as 1969 was explained away as part of the construction of a space station; the Soviets reiterated that they had no plans to go to the moon. Ultimately, bad plans aren’t much better than no plans at all, and the Soviet manned space program was killed in 1976, with no successes recorded against the six successful landings by the United States.

In the 1990s, Western journalists and diplomats were introduced to a museum hidden in the remote Uzbek city of Nukus. In it were contained hundreds of works of art from the early days of the Stalinist regime, when painters were forced to comply with the ideals of the Communist party. “Decadent bourgeois art” gave way to paintings of factories, and much of the creative output of painters at that time would have been lost completely if not for the work of Igor Savitsky, an obsessive collector.

Savitsky persuaded artists and their families to entrust him with their work. He hid it in Nukus, a city surrounded by hundreds of miles of desert.

It is a unique entry in this list in that it was not only hidden from the outside world, but from the oppressive regime all around it. Though questions remain as to how important the art itself may be, there is no question over the value of a story of something being hidden for decades, right under the noses of history’s most obsessive secret-keepers.

We’ve mentioned before that the Soviets erased one of their cosmonauts from the records for acting like a douche. More tragically, they also erased from history the first cosmonaut to die in the pursuit of spaceflight. Valentin Bondarenko was killed during a training exercise in March 1961. His existence wasn’t known in the West until 1982, and not publicly acknowledged until 1986. If you are squeamish, you will want to skip the next paragraph.

During an isolation exercise in a pressure chamber, Bondarenko made a fatal mistake. After removing a medical sensor and cleaning his skin with alcohol, he flicked the cotton bud onto the hot plate he was using to make tea and it burst aflame. When he tried to smother it with his sleeve, the one hundred percent oxygen atmosphere caused his normally flame-resistant clothing to catch alight. It took minutes for the door to be opened, by which point he had third degree burns everywhere but the soles of his feet, which was the only place on his body the doctor could find a blood vessel. Bondarenko’s skin, hair, and eyes were gone. He whispered, ”Too much pain . . . do something please . . . to kill the pain.” It took sixteen hours for him to die.

So yeah—denying his existence to avoid bad publicity was a really, really douche move.

The horror of the Soviet famine of 1932 was covered here before, but the internal and international cover-up is worth discussing in and of itself. In the early ’thirties, a number of disastrous Soviet policies led—whether purposefully or otherwise—to the deaths of several million people.

This is the sort of thing that you’d think would be hard to hide from the outside world—but luckily for Stalin and company, many in the outside world teetered between willful ignorance and knowing denial themselves.

The New York Times, along with the rest of the American press, obscured and downplayed the famine. Stalin arranged a number of carefully staged tours for influential foreigners: shops were stocked with food but anyone approaching the shops was arrested; the streets were washed clean; and all actual peasants were replaced with communist party members. H.G. Wells in England and George Bernard Shaw in Ireland let everyone know that the famine “rumours” were unfounded. Most egregiously, the Prime Minister of France paid a visit to Ukraine and described it as being like “a garden in full bloom.”

By the time the 1937 census records were made confidential, the famine had been adequately suppressed. Though the death toll was potentially on a par with the Holocaust, it’s only within the last ten years that the famine’s status as a crime against humanity has been established.

In 1966, an American spy satellite took a photograph of what appeared to be an unfinished Russian sea plane. The plane would be bigger than any aircraft the USA possessed. It was so big, experts calculated that even with the expected wingspan of a craft that size, it would be an awful flyer. Rather bizarrely, its engines were located well ahead of the wings. The Americans were baffled—and would remain so until the Soviet regime collapsed twenty-five years later. The Caspian Sea Monster, as it was nicknamed, was an ekranoplan—something between a plane and a ship, designed to fly only a few dozen feet above water or land.

Even mentioning the name of the thing was forbidden to those in the know, despite the Soviets giving the project basically as much money as it wanted. Then again, these things kicked serious ass. They could carry hundreds of troops, or a few tanks, below radar detection at over three hundred miles per hour. They’re more fuel efficient than even the best modern cargo plane, capable of being much larger, and they look goddamn epic. The Russians even built one two-and-a-half times the length of a Boeing 747, powered by eight jet engines, with six nuclear warhead launchers on the roof (because what else are you going to put atop your jet-powered-tank-delivery-ship-plane?).

Luckily, there are some fantastic collections of images and videos available online.

The Soviets’ disregard for health and safety didn’t stop with nuclear waste. On October 23, 1960, they were preparing for the launch of a new, top-secret rocket—the R-16. Using a new type of fuel, the rocket sat in a gantry packed with technicians. The rocket began leaking nitric acid, at which point the only reasonable action would be to evacuate everyone as quickly as possible.

But the project’s commander, Mitrofan Nedelin, instead ordered more staff to flock to the leak to attempt repairs . When the inevitable explosion occurred, the gantry crew were killed instantly. The fireball was hot enough to melt the tarmac—many who tried to flee were stuck in the tarry ground and burned to death. Over one hundred people were killed. It remains the worst rocket disaster in history.

The Soviet propaganda machine whirred into action. Nedelin himself was reported as having been killed in a plane crash. Reports of a massive explosion faded into the rumor mill that pervaded the whole of the USSR. It took until 1989 for the first published account to appear. Today an obelisk stands as tribute to those that died, but not Nedelin himself. Though still officially a hero, those local to the disaster site remember him less fondly as the man responsible for the loss of a hundred lives with which he was entrusted.

In 1948, the Soviet Union established a top-secret bio-weapons lab on an island in the Aral Sea, used to turn anthrax and the bubonic plague into weapons. They also developed smallpox weapons and, in 1971, conducted an open-air test. In a surprising turn of events, the weapon—designed to cause an outbreak of smallpox when activated in the open air—in fact caused an outbreak of smallpox when activated in the open air. Ten people became ill, three of whom died. Hundreds were quarantined, and fifty thousand people from the surrounding area were vaccinated in a fortnight.

The incident became known to the wider public only as recently as 2002. The outbreak was contained effectively, but despite the scale and widespread documentation of the incident, Moscow has never acknowledged its existence. This is unfortunate, as there may be lessons to be learned that could save lives if biological weapons were ever to fall into the hands of terrorists.

There’s a town in the south of Russia that didn’t show on any maps. There were no buses that stopped there, no road signs pointing towards it. Its post was addressed to Chelyabinsk-65, though the city of Chelyabinsk was nearly fifty miles away. Its name is Ozyorsk—and despite being home to tens of thousands of people, its existence was unknown even in Russia until 1986. The secrecy was because it was the home of a nuclear fuel reprocessing plant. This particular processing plant exploded in 1957—but because of the secrecy of its location, the disaster was named after another town seven miles away. That town was Kyshtym.

Ozyorsk was only one of dozens of the USSR’s secret cities. There are forty-two we know about, but also around fifteen more that people suspect Russia is still hiding. Residents of these cities were gifted with better food, schools and luxuries than the rest of the country. Those within still cling to their isolation; the few foreigners allowed to visit the cities are usually escorted by guards at all times.

In the increasingly open and global world, many are choosing to leave the closed cities, and there may be a limit to how long they can remain isolated. Yet many of these cities continue to perform their original function—whether that be housing a naval fleet, or producing weapons-grade plutonium.

We’ve talked about the Katyn Massacre before, but as with the 1932 famine, the massive international denial warrants its own entry, and its place as number one on this list. In 1940, the Soviets murdered more than 22,000 captured Polish prisoners and buried them in mass graves. They officially blamed the Nazis. They didn’t admit responsibility until 1990. So far, so predictable—but this cover-up takes number one spot because it was made possible not due to the deceit of the Soviets, but the willing cooperation of the leaders of the United States and the United Kingdom.

Winston Churchill admitted in private that the massacre was probably the work of the Bolsheviks who “can be very cruel.” Yet he insisted the Polish government-in-exile cease their accusations, censored Polish-language newspapers, and helped to prevent an independent investigation by the International Red Cross. Britain’s ambassador to the Poles described it as using “the good name of England like the murderers used the conifers to cover up a massacre.” Franklin D Roosevelt was equally unwilling to allow blame to fall on Stalin.

Evidence of the US government’s knowledge of the matter was even suppressed during a congressional hearing in 1952. In fact, for years the only major government that promoted the truth was Nazi Germany. That’s another sentence you’ll not read very often.

It would be easy to be critical of the leaders for effectively letting the perpetrators get away with it, but with Germany and later Japan to deal with there were a lot of hard decisions to be made. Allying with the world’s other military and industrial super-power was a decision made of necessity. “His Majesty’s Government have no wish to attribute blame for these events to anyone except the common enemy,” wrote Churchill.

If that common enemy, whose name has become synonymous with all that is evil, was prowling at our own shores—we might be hard-pressed to do any differently.

Alan has failed to enter the current decade and so has never posted on Twitter. He is definitely not the writer of the same name with 11,000 Twitter followers and a Wikipedia article. He intends to start a blog one day but is waiting for something useful to say.