History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Great Hoaxes of the Twentieth Century

Hoaxes: they might not make the world go round, but they certainly make the ups and downs of life a little bit easier to bear. Whether we’re talking about a German Army impostor, or a mischievous history of the bathtub, the turn of the twentieth century was a hotbed for cheeky chaps and chapettes who wanted to take the mickey out of the gullible masses. So without further ado, here are some of the best hoaxes from 1900 to 1929:

Aeroplanes were a big deal at the start of the twentieth century. All you needed was the vaguest hint of a successful flight, and journalists would clamber over each other to get an exclusive interview. And the hoaxers of the time preyed on that very fact.

One such hoaxer was Wallace Tillinghast: Vice President of a Worcester manufacturing company in Massachusetts by day, and aeronaut extraordinaire by night. In December 1909, the Boston Herald reported that Tillinghast had built the most advanced aircraft the world had ever seen—reaching speeds of up to one hundred and twenty miles per hour and able to carry a whopping three passengers! To date, the greatest feats of flying had been the 1903 achievement of the Wright brothers—who had succeeded in flying the first heavier-than-air craft—and the flight of Louis Blériot across the English Channel earlier in 1909. With his “monoplane”—with a wing span of seventy-two feet (22m)—Tillinghast was all set to be the next big thing.

Towards the end of 1909, several US newspapers reported that Tillinghast had taken the plane on a 300 mile (483km) test run—and despite an engine failure (which Tillinghast had supposedly fixed 4,000 feet up)—he had landed safely.

Now, journalists of course wanted to see this remarkable monoplane. But Tillinghast wasn’t forthcoming. In fact, he refused to reveal any evidence relating to his flights, citing anxiety about others stealing his invention. Eventually he would succumb to pressure, and agreed to show his super-plane the next February.

As February came and went, the game was finally up. Despite the fact that Tillinghast never ever admitted his hoax, the director of the New England Aero Club called an end to the whole fiasco—releasing a statement saying that Tillinghast had never even sat in a plane, let alone flown one.

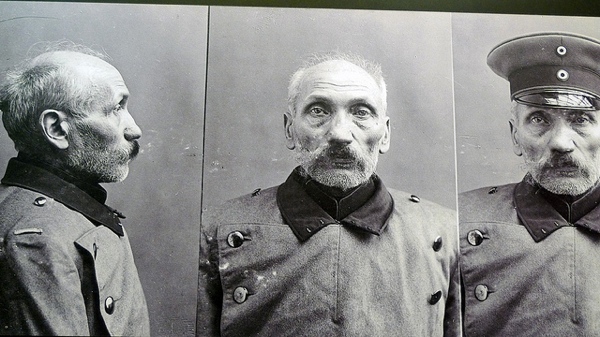

In October 1906, the unemployed German cobbler Wilhelm Voigt made his move. He pulled on his military captain’s uniform—purchased from a thrift store—and walked out onto the street, right into the path of a group of German grenadiers. Ordering them to halt, Voigt took control of the company and marched them to the town hall of Köpenick (a suburb of Berlin), where he arrested the mayor and the treasurer on charges of embezzlement.

He also stole 4,000 marks while he was at it, before disappearing with the loot. Nine days later, Voigt was arrested by the police and sentenced to four years in prison. But he was released after only two years, when Kaiser Wilhelm pardoned him due to swelling public opinion of the impostor; Voigt had become something of a cult figure for humiliating the gullible German army.

On February 7, 1910, the Prince of Abyssinia and his posse were welcomed aboard the H.M.S. Dreadnought, the British Navy’s most dominant battleship of the day. Despite a surprise visit, the ship’s Commander-in-Chief still managed to order his men to stand to attention, and the Prince was clearly flattered by the reverence shown by the British Navy.

Over the next hour or so, the Prince and his men were given a full tour of the warship, expressing suitable amazement at everything on display. After a successful tour, the Prince and his entourage departed the ship as the British national anthem boomed out in the background.

Fast-forward to the next day: the ship’s Commander-in-Chief learns that the “prince” had not been a prince at all. In fact, the whole group had been a gang of cheeky upper class impostors, with their faces painted black, dressed in authentic robes. They had forged a telegram and sent it to the ship’s communication mere minutes before arriving on deck.

But these upper class rich kids were no motley crew. They were future members of the Bloomsbury Group of artists and writers, featuring none other than a bearded Virginia Woolf.

Austrian scientist Paul Kammerer was an advocate of a radical theory called Lamarckianism. The theory proposed that a person could acquire a physical defect, such as a limp or scar, from their hereditary line—the proof of which would have had drastic ramifications for evolution.

To validate his theory, Kammerer created an experiment called the Midwife Toad. Most toads have black, scaly lumps on their back legs in order to help them cling to one another in the water, where they commonly mate. The Midwife Toad, however, only gets busy on land—and therefore doesn’t have any need for such bumps. Kammerer believed that if the Midwife Toad was forced to mate in water, it would “evolve” the same bumps that its other toady friends possessed.

In keeping with Lamarckian inheritance theory, the Midwife Toad’s offspring would therefore inherit these bumps as well. Over several years, and several generations of Midwife Toads, Kammerer announced his success. He had spawned an entire generation of Midwife Toads with black scaly marks on their back legs. Kammerer had proven that Lamarckian inheritance existed.

Recognising that such a dramatic revelation would have huge implications for evolutionary theory and the process of inheritance, one Dr. G.K. Noble, Curator of Reptiles at the American Museum of Natural History, strenuously examined Kammerer’s experiment. Noble discovered that the generation of Midwife Toads didn’t have the scaly black marks after all; they were in fact ink blots from ink which had been injected into the toad’s skin.

Kammerer was exposed as a fraud. But he protested his innocence, and insisted that one of his lab technicians must have tampered with the experiment. We shall never know whether or not this is true: mere days after his humiliating fall from grace, Kammerer tragically took his own life.

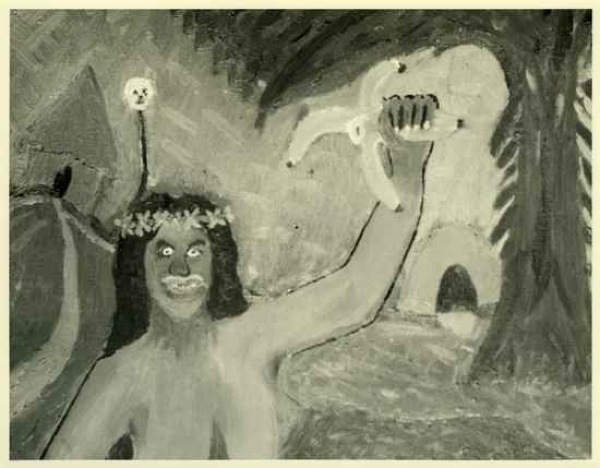

When US author and Latin expert Paul Jordan Smith heard that his wife’s paintings had been slagged off by critics, he decided to have some fun. Bored one day in 1924, he picked up a paint brush and splashed out a picture of somebody holding a banana (he was actually trying to paint a star fish). That night, he went to bed as Smith and woke up as Russian artist Pavel Jerdanowitch.

In 1925, Smith entered the painting (Yes We Have No Bananas) in New York’s Exhibition of the Independents. As soon as it was put up on the wall, critics loved what they saw, some even comparing him to Gauguin. “Jerdanowitch” quickly became a much sought-after name in the art world, coveted by art journals of the time—including the highly respected Review of the True and the Beautiful, a French publication. Smith replied with an extensive account of Jerdanowitch’s life, claiming he was the founder of the Disumbrationist school of art.

After four more paintings, and a whole lot of support and praise (one critic called his work “inspirational”), Smith had had enough. In 1927, Smith revealed his deception to the LA Times. It was printed on the front page the following morning. Smith was quoted as calling art critics of the time “fraidy cats” and the contemporary obsession with abstract art “poppycock.”

In 1907, the Hammerstein Victorian Theatre in Broadway advertised a woman called Sober Sue, who would supposedly appear on stage during the intermission of whatever show was on at the time. The advertisement came with a challenge: make Sober Sue laugh and take home $1,000 (although this fee has likely been exaggerated over the years).

Throughout the summer, people came from all parts to try to make Sue crack a smile; eventually even New York’s most revered comics turned up, churning out their best crowd pleasers in the hope of grabbing the headlines for being the first comedian to get Sue to chortle. But they had no such luck.

As the winter closed in, the advertisement was taken down and Sober Sue moved on to pastures new. It was then and only then that the promoters admitted their con; Sober Sue suffered from facial paralysis, and the whole set-up had been a ruse to get the best comics in the land to perform their show-stealing jokes for free.

Emile Fradin was a seventeen-year-old farmer in central France with little to his name but the small patch of soil he worked on. One hot afternoon, Fradin told his grandfather that he’d found an underground chamber containing mysterious artifacts. Soon enough, local amateur archaeologist Antonin Morlet popped over to have a look. What he found was shocking. Inside the chamber there were all manner of things, from glass bricks to human bones to hermaphrodite idols; there was also a ceramic tablet inscribed with an unknown language, which Morlet dubbed “Glozellian script.”

Rumors of this remarkable find of artifacts from an unknown ancient culture spread through France. Eventually, the International Institute of Anthropology visited the site and claimed that the artifacts were fakes. But a few months later, other experts visited the site and claimed that the artifacts were in fact remnants of the Neolithic period. This are-they-aren’t-they pattern continued all the way to the 1980s; during this time, Fradin had successfully sued the head of the Louvre art gallery for defamation, and had himself himself been charged with fraud.

At the centre of the argument was a worldview-shattering hypothesis: if the Glozel tablets were authentic, they would lead to the rewriting of history, as the language predated any account of the Western alphabet; and so they would have given rise to the notion that central France was the starting point for human civilization.

Despite many of the artifacts in the cave being attributed to different eras (in the 1980s the bone fragments alone were carbon-dated and found to date from any time between the thirteenth and twentieth centuries), it has not been so easy debunking the Glozel text as a hoax.

The truth is, experts are still divided over whether or not the texts are fakes. Fradin himself died in February 2010 at the grand old age of 103, having lived on the farm in relative peace since the 1930s. He always claimed the tablets and artifacts were a legitimate find and no-one will ever again be able to tell him otherwise.

When the BBC interrupted a broadcast on 16 January 1926, no one would dare question the veracity of the “special announcement”: a disgruntled mob of the unemployed were smashing and crashing through the streets of London, leaving utter chaos in their wake. The National Gallery had been looted, the Savoy Hotel destroyed, the Houses of Parliament besieged with mortar fire, Big Ben toppled, and the Minister for Transport hanged from a lamppost. This was revolution, live on the radio. As the presenter spoke, shouts and explosions could be heard in the background.

Within the city of London itself, people started to panic, fleeing their homes and calling the authorities. But all the BBC had played was one of Father Ronald Knox’s comic shows, Broadcasting the Barricades—a series of joke news bulletins, one of which featured a “red riot.” Perhaps if some people had listened harder rather than freaking out, they would have realized that the nightmare was a fabrication. Especially if they had heard that the leader of the revolutionaries was one Mr. Popplebury, who also happened to be the “Secretary of the National Movement for Abolishing Theatre Queues.”

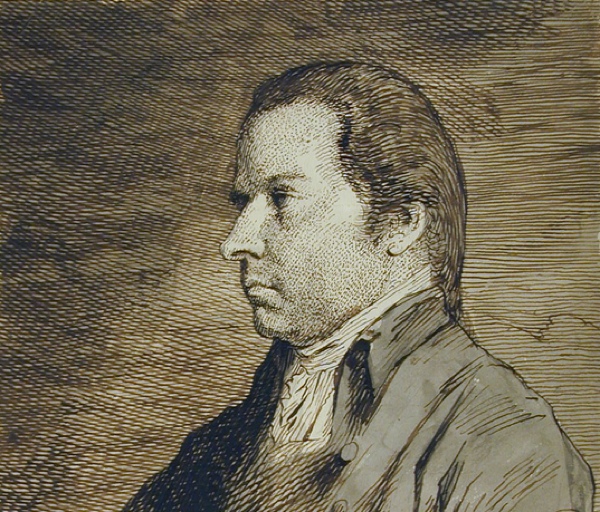

By all accounts Francis Douce (1757-1834) was a well-respected antiquarian, highly regarded for his vast collection of books, drawings, and artifacts—with subjects ranging from children’s parlor games to demonology. For a brief time he was also Keeper of Records at the British Museum.

But Douce’s tenure there was not a happy one; he found the administrative duties constricting, and the people who worked there difficult to get along with. Douce died in 1834, leaving behind his epic collection. In his will, he requested that a particular box of unfinished papers, and a few rare texts, be donated to the museum—on one proviso: they were to remain in a sealed container until sixty-six years after his death.

The trustees of the museum waited all those years, until finally they opened the box on January 1, 1900, expecting to find within a cornucopia of information and rare texts. For why would someone insist that fellow academics wait so long, if the content of the box wasn’t of some importance? Holding their breaths, they unsealed the box, peeled off the lid, and … nothing. Except for a few scraps of note paper and a couple of torn book covers, there was nothing of any cultural importance. Some years later in 1930, the box was transferred to the Bodleian library at Oxford University, where the contents were helpful in pinpointing some of Douce’s more unusual pieces—but by then, nearly one hundred years after his death, Douce was no doubt still chuckling away in his grave.

Joan Lowell had one of the most remarkable childhoods anyone could ever wish to have. From the ages of one to seventeen, Lowell lived aboard her father’s schooner, the Minnie A. Caine, sailing the high seas.

Her remarkable life included many adventures: she claimed she’d never had a female role model, and only learned about female anatomy by cutting up a shark; she once harpooned a whale; she frequently played—and lost—strip poker with the crew; witnessed grown men drowning overboard; and survived a shipwreck three miles off the coast of Australia by swimming to shore with—wait for it—three kittens clawing on to her back.

All her adventures were recorded in her autobiography, The Cradle of the Deep, published in 1929 by Simon and Schuster, and for which Lowell was paid $50,000. Film rights followed, as did numerous outstanding reviews for the book (adventure-autobiographies were all the rage at the time). But as often happens, naysayers soon crawled out of the woodwork—and doubts as to the truth of the tale were confirmed when the San Francisco Chronicle examined Lowell’s upbringing. It turned out that she’d really grown up in Berkeley, California, and had been out to sea for a handful of short trips.

Lowell always claimed that the book was eighty percent genuine, although she did admit to taking some artistic license with the tale. In a famous interview some years later, she admitted that if she hadn’t added a little spice to the story of her life, it would all have been a bit dull.

Gareth May is an author and the co-editor of relationship website His ‘n’ Hers Handbook. His debut book, 150 Things Every Man Should Know, published in November 2009, was selected as one of the best books of the year by The Independent on Sunday. It has been published in the USA, Russia and China. His second book, Man of the World, was published in June, 2012. Born and bred in Devon, he now lives in London.