Technology

Technology  Technology

Technology  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff The 10 Unluckiest Days from Around the World

Food

Food 10 Modern Delicacies That Started as Poverty Rations

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Shared TV Universes You’ve Likely Forgotten About

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 of History’s Greatest Pranks & Hoaxes

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff The 10 Unluckiest Days from Around the World

Food

Food 10 Modern Delicacies That Started as Poverty Rations

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Shared TV Universes You’ve Likely Forgotten About

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 of History’s Greatest Pranks & Hoaxes

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

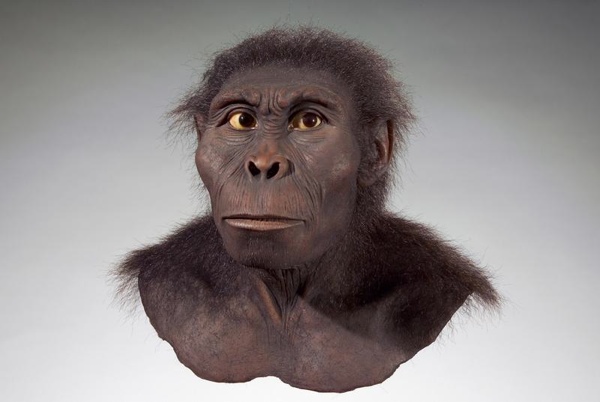

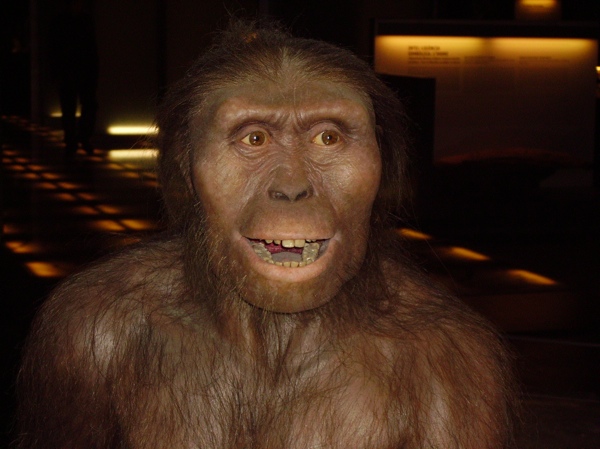

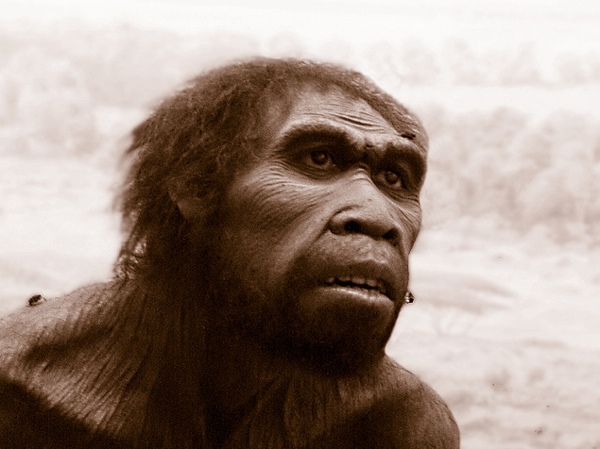

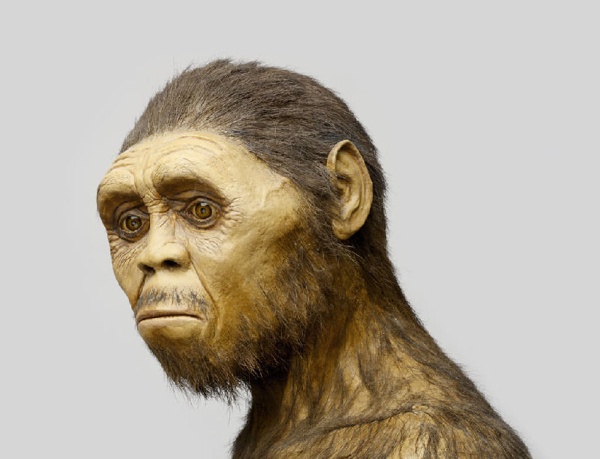

10 Transitional Ancestors of Human Evolution

The evolution from our closest non-human ancestor to present day humans is one with many transitions. Some of these transitions are widely agreed upon by the scientific community while others are shrouded in frustrating darkness. Below are the ten species that have added the most to our lineage, some adding seemingly simple advances like walking on two legs and chewing food differently to mastering fire and dominating every other species on Earth.

The beginnings of our lineage away from the Great Apes really start with the separation from chimpanzees, our closest non-hominin relative. This lineage split occurred around 5.4 mya (million years ago), and many scientists believe S. tchadensis is that transition. A distorted skull was found in the Djurab Desert of Chad in 2001 and was dated to around 6-7 mya. By looking at the way the skull attaches to the skeleton it can be inferred that S. tchadensis was bipedal, possibly a sign showing they left the trees and began walking upright. The controversy begins when looking at the size of the braincase, in S. tchadensis only about 350 cc (cubic centimeters) versus the chimpanzees 390 cc brain. Furthermore, scientists argue the skull was so fragmented and distorted that it shouldn’t be a hominin (species closer to humans than chimps) but possibly produced chimps or gorillas (a split occurring about 6.4 mya).

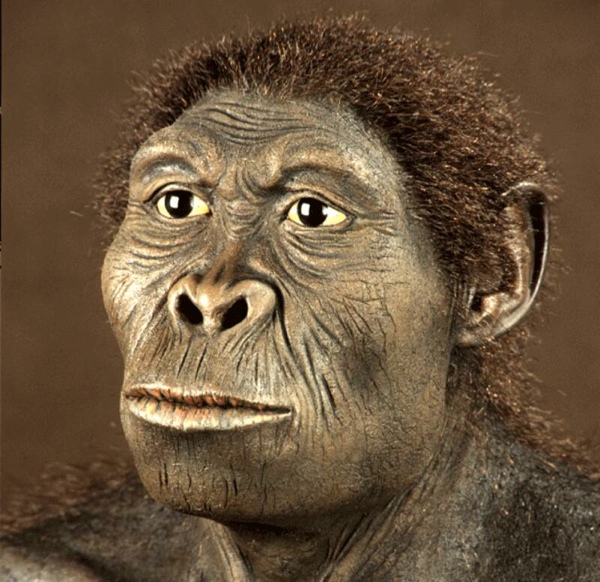

Found at Lake Turkana, Kenya in 1999, K. platyops changed the way paleoanthropologists viewed our ancestral tree. The skull was dated to around 3.5 mya and supported a 400 cc brain, a bit bigger than chimpanzees but only a third the size of modern humans (around 1200 cc). One of the most significant changes is in its name. Platyops means flat face, a subtle morphology shift indicating a change in jaw usage meaning K. platyops found a different ecological niche. The size of the molar teeth point to a species that chewed its food, coupled with the different jaw usage shows K. platyops was adapting to changes it encountered. Again controversy comes into play with some saying K. platyops shouldn’t belong to its own genus but actually belongs to the Autralopithecus genus.

In 1974 at Hadar, Ethiopia researchers discovered about 40% of a skeleton came to be known as “Lucy.” Lucy was an incredible find because there were so many bones to examine instead of the typical skull or bone fragments. The skeleton suggests a female of 64 lbs and a height of 3 ft 7 in that walked upright. This can be shown from the pelvis resembling a modern human and a tibia/femur design supporting bipedal locomotion. From the waste up Lucy looked and acted like an ape, with her ~440 cc brain and long arms, but from the waist down was human. This may have supported a life of spending the day on the ground and the night sleeping in the trees.

Another find was Selam, a skull and skeleton fragments from a three year old female dating back to 3.3 mya. The skull had a brain capacity of 330 cc which suggests a total adult capacity of about 440 cc; quite a bit slower than a chimpanzee. One of the biggest differences between humans and other mammals is our incredibly large brains in relation to our body size. When a human baby is born it is totally reliant on the mother for everything, with suckling and grasping being its only real attributes. It takes about 25 years for our brains to become fully developed while chimpanzees are complete by age 3. This may be due to the new information required to learn with the advent of bipedalism and the way of life that comes along with it.

Another interesting difference between chimps and humans is the presence of the lunate sulcus in chimps. This divides the occipital lobe (involved in sight) from the rest of the brain. Modern humans don’t have this sulcus while our brains have a large neocortex larger than our occipital lobe, it turns out Selam’s brain was heading in that direction. When a plaster cast of the skull was made scientists found the lunate sulcus was moving back, making smaller the occipital lobe and expanding the neocortex. This suggests Selam could have had greater reasoning skills and more control of motor functions.

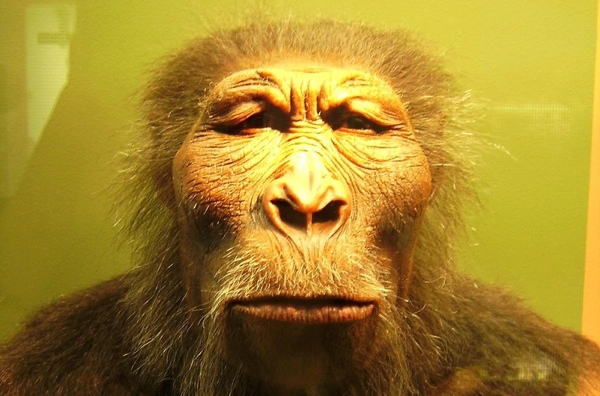

The genus Paranthropus had fairly small braincases, about 500-550 cc or 44% that of modern humans. They were bipeds, roughly the same size as the Australopithecus genus, but what separated these guys from the rest was their face and mouth. They had very large faces with a significant narrowing of the skull above their brow line. P. boisei, also known as “Nutcracker Man,” had teeth four times the size of modern humans with a tremendously thick layer of enamel dwarfing any hominin found. Complimenting these gigantic teeth were massive jaw muscles connected to a bony crest on top of the skull. This allowed P. boisei to have a diet of harsh, tough foods like nuts, seeds, and ground tubers. Researchers believe the advantage of eating tubers made it easier to meet the caloric requirements raised by a larger brain.

A fitting first member of our own genus, H. habilis was the first on our ancestral path to use stones as tools, an attribute giving them the name “Handy Men.” They began breaking the long bones of animals to get to the marrow inside facilitating their diet consisting of a variety of meats. Their thumbs were broader than before adding to the dexterity inherent to modern humans, possibly advancing their stone tool making. Members of this species stood between 3-4 feet tall, had less of a snout and more of a nose, and an elevated forehead different from the sloped morphology of the Australopithecus and Paranthropus genus before them. Their brain’s were about 510 cc or 43% of modern humans with an expansion of the frontal lobe, the area dealing with rational thought and problem solving.

H. habilis may have been so successful due to climate change occurring at such a rapid rate. In a span of only thousands of years large lakes would become desert which would then become lakes again. This is thought to have sped up brain development because adaptations had to be made in order for the Homo genus to continue on.

H. ergaster had a dramatically increased brain than any species before it, measuring in at 850 cc or 71% that of modern humans. They may have been the first to harness fire, had a multitude of stone tools that were more sophisticated and becoming more unique. The species had a smaller, flatter face with teeth and jaws smaller than before. The males and females weren’t structurally as different, less sexual dimorphism, which all species before did not have. There is also evidence of an early form of symbolic or linguistic communication.

In 1984 Richard Leakey came across a skeleton near Lake Turkana, Kenya belonging to an 8-11 year old male from 1.6 mya. The boy was 5 ft 3 in tall with wide hips and long, thin arms. He was part of the H. erectus species which is characterized by making tools, controlling fire, and living in small groups. Group living was an important manifestation due to its societal implications. There is speculative evidence supporting the link between cooking and fire building with group living. H. erectus was totally on the ground now so they needed fire to keep predators away, with this need for protection came a reliance on each other for safety which garnered an advantage to those who protected others. Some argue this is why human babies can easily have numerous caregivers since our ancestors took turns raising the young in a tribal manner. This also instilled the skill to read into others and ascertain a “good” person from a “bad” person. Some of the most compelling evidence of communal living came from a male H. erectus skull with no teeth from old age. Since he wouldn’t have been able to chew his food researchers suggest he was fed by others or possibly had others chew his food for him. This shows a caring for others and a transition of the brain from only caring about self-preservation to the well fare of the group.

The brain of Turkana Boy was 900 cc, two times the size of chimps and 75% the size of modern humans. There is also evidence showing Turkana Boy had a fully modern Broca’s Area which controls memory, executive functions, and motor actions of speech. This was a dramatic jump in brain volume and capability which could have accounted for the increase in intellect and possibly speech usage. The problem with bigger brains is more energy needed to support it; luckily H. erectus had an answer for that. Having the ability to run on two legs was much more efficient than on four. Along with two legs they also had much less body hair than ever before which allowed for sweating. These two combined meant H. erectus could efficiently chase down four legged prey to the point of exhaustion while H. erectus could sweat to stay cool. This greatly increased hunting which provided meat, containing fats and proteins, to support the caloric intake needed for their brains.

Religion is a trait humans have possessed throughout all of civilization, but civilization only really goes back about 10,000 years. There is evidence pointing to H. heidelbergensis burying their dead together with a ceremony involved. In Northern Spain at the Pit of Bones there are many skeletal remains found in a deep cave indicating H. heidelbergensis dropped them down the pit in some sort of ritual. Scientists have also found a pink quartz hand axe buried along with them indicating a possible offering to a sort of god or a belief in a life after death.

There is evidence showing the brain volume to be 1100-1400 cc, larger than that of modern humans. Researchers believe H. heidelbergensis was capable of planning, symbolic behavior, and was the first species to build substantial shelters. There are some scientists that believe this species gave rise to both the Neanderthals and modern humans simply by traveling. About 300,000 to 400,000 years ago H. heidelbergensis traveled out of Africa and moved to what is now Europe, these ancestors became H. neanderthalensis while those who stayed in Africa developed into H. sapiens.

If there was one species of hominin that should have scared modern humans it was the Neanderthals. This species had brains slightly larger than H. sapiens, had thicker bodies, and were mostly carnivorous in their diets. Their Broca’s area of the brain was thoroughly human which indicates speech was possible. They may have had smaller parietal and temporal lobes which indicates thinking patterns, memory, and their ability to manipulate objects was less advanced than H. sapiens.

Neanderthals had only a few, simple tools such as heavy spears or knives to kill game. This meant they had to get close to their prey in order to kill it, resulting in shortened life spans and many skeletons found with fractures and breaks. The diet was extremely meat heavy with little to no evidence suggesting any kind of vegetable intake. In all the environments found the diet is the same, suggesting low ability to adapt to their environment. A possible cause of extinction could have been the climate swings indicative of Europe around 30,000 years ago mixed with their low adaptability or H. sapiens presence could have pushed them to areas where life was too difficult.

We have finally reached the pinnacle of human evolution, characterized by adaptability, sophisticated tool making, and the harnessing of fire. It is difficult to look back and think that by some indications we almost didn’t make it. Around 140,000 years ago Africa experienced a mega drought that made most of the tropical areas uninhabitable. This forced H. sapiens to the coasts and by some estimates dwindled down to only about 600 breeding individuals. This is where the greatest evolutionary gift of mankind comes in, adaptability. Homo sapiens started living off the sea, eating berries, hunting in the grasslands, and living in nearby caves. Technology began to increase by making fire-hardened, diverse tools designed for specific functions. They started caring about appearance as seen through shells with holes in them for necklaces and painted their bodies.

H. sapiens began traveling to Europe where they might have met the Neanderthals. H. sapiens had varying advantages such as slimmer bodies requiring less caloric intake, developed projectile weapons making hunting safer and more efficient, adaptation widened their ecological niche, and culture allowed H. sapiens to pass beneficial knowledge to future generations.

Tyler G. is an Oregonian with a love for the outdoors, anything science, and all kinds of twentieth century literature.