Sport

Sport  Sport

Sport  Animals

Animals 10 Strange Times When Species Evolved Backward

Facts

Facts Ten Unexpectedly Fascinating Facts About Rain

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of Australia’s Gruesome Unsolved Wanda Murders

Humans

Humans 10 Unsung Figures Behind Some of History’s Most Famous Journeys

Animals

Animals 10 Species That Refused to Go Extinct

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Weird Things People Used to Do at New Year’s

Our World

Our World 10 Archaeological Discoveries of 2025 That Refined History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Fascinating Facts You Might Not Know About Snow

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous Top 10 Things Crypto Was Supposed to Change & What Actually Did

Sport

Sport The 10 Least Credible Superstars in Professional Sports

Animals

Animals 10 Strange Times When Species Evolved Backward

Facts

Facts Ten Unexpectedly Fascinating Facts About Rain

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of Australia’s Gruesome Unsolved Wanda Murders

Humans

Humans 10 Unsung Figures Behind Some of History’s Most Famous Journeys

Animals

Animals 10 Species That Refused to Go Extinct

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Weird Things People Used to Do at New Year’s

Our World

Our World 10 Archaeological Discoveries of 2025 That Refined History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Fascinating Facts You Might Not Know About Snow

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous Top 10 Things Crypto Was Supposed to Change & What Actually Did

10 Microorganisms You Can Find in Drinking Water

Warning: This list is not for the faint of heart. There are invisible monsters living in your tap water, creatures that swim and multiply by the billions inside every drop of brisk, refreshing water you slurp down your gullet, tiny demons that…well, okay, they’re actually not all that bad. All water has bacteria and protozoans to some extent, most of them completely harmless. But once you see what they look like up close and personal, you might never get the image out of your head. Here are 10 microorganisms that could be living in your drinking water right now.

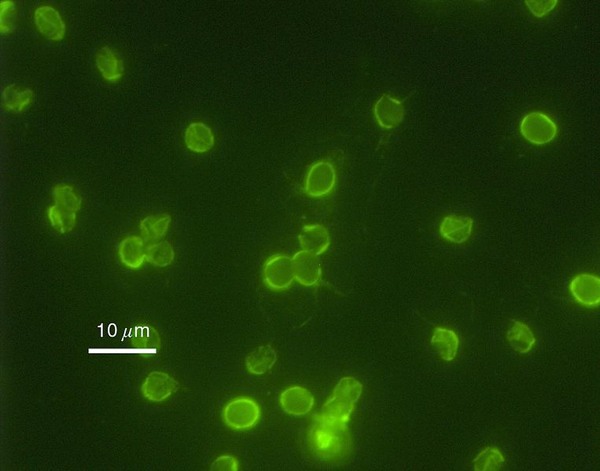

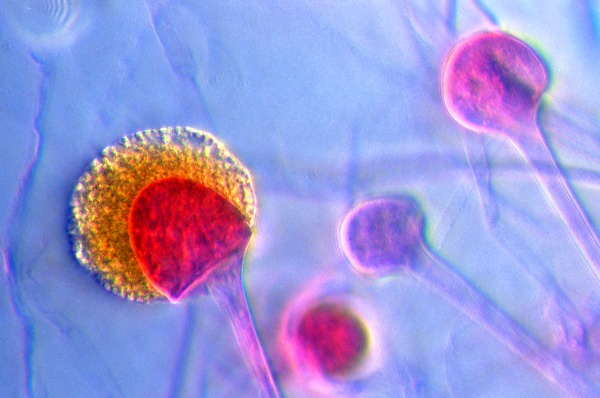

When cities pump water out to their residents, they put the water through a series of filtration and disinfection steps first. This is obviously beneficial because when you pull water from lakes and rivers it’s most likely going to be filled with bacteria. Filter it, and you can get most of that bacteria out. The important word there is “most,” because even the most advanced filtration techniques are not infallible. And for many people, that means drinking tiny doses of cryptosporidium every day.

Cryptosporisium is what’s known as a protozoan—a single-celled organism—and is most famous for giving people bouts of crippling diarrhea, a condition affectionately referred to as cryptosporidiosis. The protozoa works like a parasite, latching onto the intestines and laying eggs in a person’s fecal matter—and that’s how it spreads: when drinking water becomes contaminated with infected fecal matter, crypto moves on to new hosts. We have safeguards in place to stop it from happening, but on a good day it only stops 99 percent of the cryptosporidium. In 1998 a crypto bloom broke out in Sydney, Australia. Officials noticed the rise, but didn’t act for a few days because the levels were still “within acceptable health limits.” That means that there are acceptable levels for a diarrhea-inducing parasite that comes from poop in your water.

This pleasant looking slinky is Anabaena circinalis, a cyanobacteria that lives in freshwater reservoirs around the world, notably Australia, Europe, Asia, New Zealand, and North America. Cyanobacteria like this are believed to be some of the first multicellular organisms on earth, and as such have evolved to do some very curious things. In the case of Anabaena spp., those things are the production of neurotoxins. The discovery of Anatoxin-a was one of the first cases of a neurotoxin being produced by cyanobacteria, and we found out in a big way: An outbreak in the 1950’s got into the drinking water supply and was responsible for a series of mass die-offs at cattle farms across the U.S.

In Australia, freshwater Anabaena bacteria have been found producing saxitoxins, a type of neurotoxin that causes respiratory arrest, followed by death. The military has even gone so far as to classify saxitoxins as Schedule 1 substances with “no practical use outside of weapons manufacture.” Fortunately, cyanobacteria are one of the easier microorganisms to filter out of drinking water. For now.

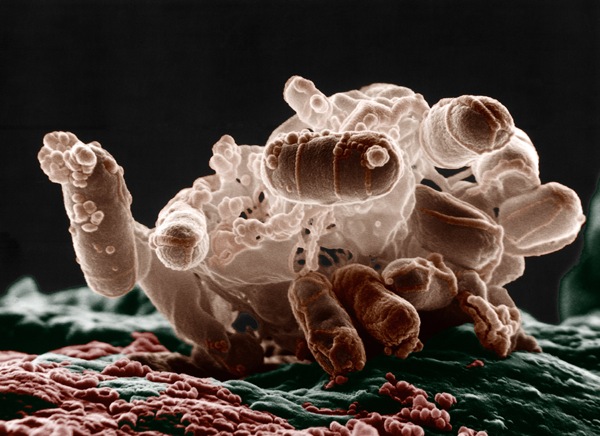

Rotifers are a relatively common microorganism that can be found pretty much everywhere in the world. And they’re also one of the most common drinking water contaminants, despite growing as large as 1mm at times (which is hardly microscopic—you can see that with your naked eye). Some of them swim, others crawl around with an inchworm motion, but none of them are known to be harmful to humans. And that’s good, because they show up in tap water fairly often.

What’s not good is that the presence of rotifers in a municipal water supply usually means that there is a problem with the filtration system—organisms that large should not be able to make it through. And rotifers are also known to act as hosts to protozoans (like cryptosporidium) and bacteria. That leads to a mirrored benefit, of sorts: rotifers can be used as a warning system to let officials know that there’s something wrong with their systems, but by the time they’re seen, there could be other things that got through as well.

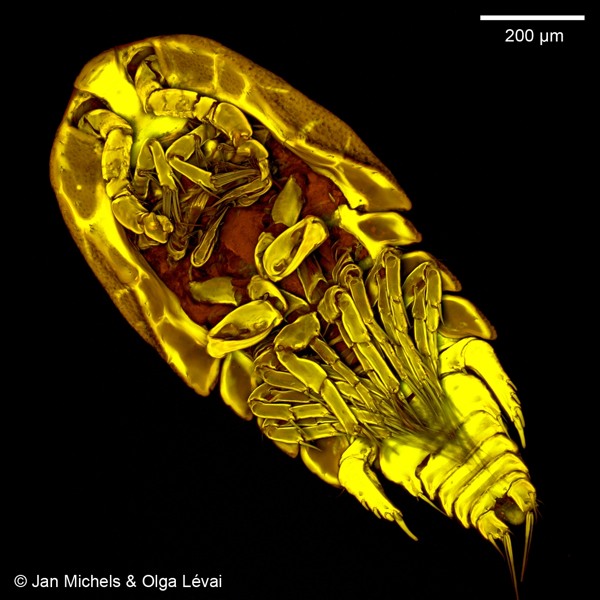

The link in the previous entry pointed to a Connecticut public health bulletin meant to advise residents who might find tiny bugs swimming around in their tap water. It addresses two types of near-microscopic invertebrates: rotifers, and copepods. Of the two, copepods are larger, and possibly even more common. They can grow up to 2mm (double the size of rotifers), and they’re actually a type of crustacean, sort of like miniature shrimp. And they’re everywhere.

In the Connecticut incident, which happened in 2009, residents began finding thousands of them in small samples of water. One resident compared them to “tiny polliwogs,” and stated, “It was completely disgusting. We were drinking them, washing out clothes in them, and it was just completely nasty.” But if anything, copepods are beneficial because they often feed on toxins. Again though, the fact that they can make it through the filtration system means plenty of smaller bacteria can too.

We all know about E. coli, or Escherichia coli, a bacteria that lives in, on, and around fecal matter. It’s been publicized more times than you can shake a stick at, until by now it’s practically a legend of the bacteria world. From food to water to even more food, it’s hard to get away from. Which is why it’s sort of disconcerting to find out that all drinking water invariably has E. coli in it; it’s just kept down to levels that are considered “safe.”

Here’s the data sheet on drinking water contaminants from the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, of the United States. According to that sheet, E. coli is acceptable as long as it doesn’t appear in more than 5 percent of the water samples collected in a given month. So if the municipality tests their water 100 times in a month, 5 of those samples can be infected with E. coli, but the water will still be permitted to go out to the city’s residents. And once you get down to decimal places of hundredths or thousandths of a percent, you are pretty much always guaranteed to find some E. coli swimming and playing in your water.

In the world at large, the more colorful something is, the more fun you can probably have with it. And based on that logic, these mycotoxic mold spores are just a big barrel of laughs. Until they start showing up in drinking water; then you have problems. Rhizopus stolonifer is more commonly known as black bread mold; leave a piece of bread out in the open, and this will be just one of the molds that take over it.

Widely considered the most common fungus in the world, it’s not surprising that this mold shows up in tap water as well. Fungi reproduce with spores which, much like flower pollen, float through the air until they find a suitable place to land and grow. In 2006, a study looked at the concentrations of mold spores in tap water, and found that Rhizopus stolonifer appeared 2.9 percent of the time, which, arguably, is fairly low in the realm of contaminants (remember, E. coli can legally show up nearly twice as often). It’s believed to release toxins that are harmful to humans, although they’re only dangerous in higher concentrations.

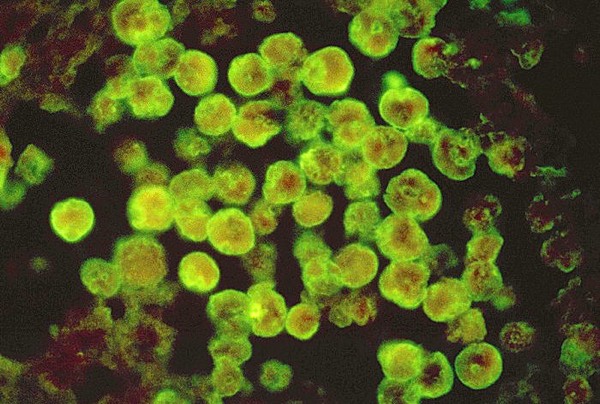

This organism doesn’t look as terrifying as some of the other creatures on this list—really it just looks like a few mold splotches. It’s actually an amoeba, though, and it eats brains. To be scientific about it, the amoeba attacks a person’s nervous system by entering through their nasal cavities, killing 98 percent of its victims.

N. fowleri infections are rare, mostly because it isn’t effective if it’s consumed orally. But in 2011, two Louisiana residents died from meningoencephalitis (the disease caused by Naegleria) after making a nasal flush out of salt and tap water. When the deaths were investigated, the brain eating amoeba was found on the bathtub, shower heads, and sink faucets—the house was literally covered in it. Despite this case, most infections aren’t caused by tap water infected with N. fowleri. No, usually people get it by swimming in lakes and rivers. Have you ever accidentally sucked water up your nose while swimming?

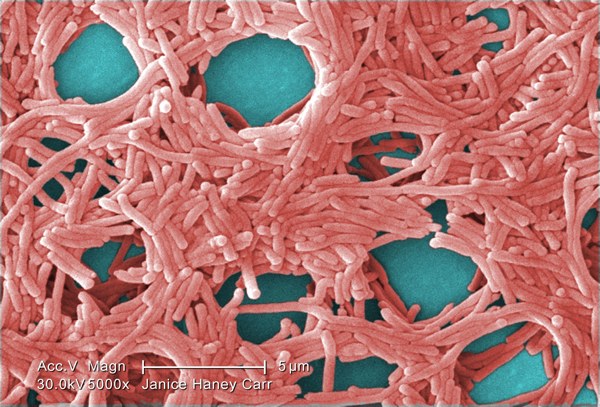

With a name like Legionella, this bacteria already sounds dangerous. And since it was named after an American Legion convention in 1976 where it was responsible for 34 deaths and a total of 221 infections, that might be a fair assumption. The condition caused by L. pneumophila is now called Legionnaires’ disease, and it sends 18,000 people to the hospital every year. And it comes from, you guessed it, contaminated water. Symptoms of Legionnaires’ disease include confusion, fevers of up to 107 F (41.5 C), loss of coordination, vomiting, diarrhea, and muscle aches. It shows up sporadically; in 2001, more than 700 people in Spain were infected in one centralized area.

As if L. pneumophila wasn’t already dangerous enough, the U.S. military decided to take a crack at weaponizing it, leading to a genetically modified version with a 100 percent kill rate. But even if you’re not on a government hit list, you would do well to stay away from water in general.

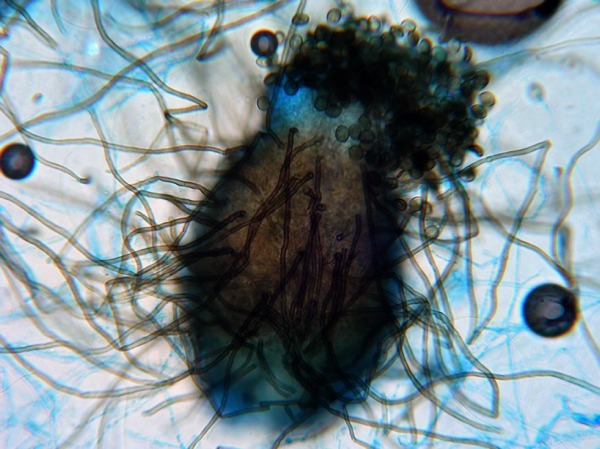

Here’s another type of mold, and one that looks slightly more terrifying than the psychedelic funhouse in number five. Like black bread mold, Chaetomium species are fairly common in everyday life, usually floating through the air in moist locations, which can encompass everything from a swamp to your bathroom ceilings. This appears in tap water fairly rarely, but when it is there it usually makes the water taste and smell slightly “off”—normal signs to stop drinking a glass of water in any case.

Chaetomium sp. spores aren’t particularly dangerous, although in some cases they can cause an infection known as phaeohyphomycosis, which is something you definitely do not want to Google. They can also present a hazard to people who are allergic to the spores, and even that typically only happens with chronic exposure.

One of the first things we learn as children is that you always cook chicken, and if you handle it raw you better scrub those hands nice and good. The reason, of course, is salmonella, which has such a long history of infection it’s not even possible to link to them all here. Usually salmonella shows up on food such as beef, spinach, and of course, chicken (hedgehogs too, surprisingly). Less commonly, salmonella causes outbreaks through none other than our friendly neighborhood drinking water.

In 2008, Colorado tap water was responsible for 79 cases of salmonella poisoning, which caused fevers and vomiting. People with weak immune systems, like the elderly, are especially susceptible to salmonella. Another study looked at the water supply of Togo, Africa, and found 26 cases of salmonella contamination, suggesting that developing countries are at a greater risk for bacterial infections from drinking water. It’s sort of common sense, but it’s beneficial to have figures to see what exactly is causing illnesses in these areas.

As Benjamin Franklin once said, “In wine there is wisdom, in beer there is freedom, in water there is bacteria.” We’ll take the wine.