The Arts

The Arts  The Arts

The Arts  History

History History’s Ten Most Lopsided Battles Ever

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

The Arts

The Arts 10 Iconic Masterpieces Attacked by Pure Pettiness

History

History History’s Ten Most Lopsided Battles Ever

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

9 Reasons Caligula And Nero Were Saner Than You Think

Rome’s two most famous emperors share more than just a family tree. Both Caligula and Nero assumed the throne at a young age; grew increasingly more depraved; lost the support of the Roman people; and were assassinated—that’s the popular story, at least.

One more thing, though—Nero and Caligula each possessed an arrogance that enraged the Roman elite, the same class of people responsible for writing the histories and letters which have informed our impressions of the two emperors to this day.

It turns out that the pen is mightier than even the scepter, since most of what is believed today about Rome’s bad boys stems from those hostile claims. Cruel—yes. But insane? You be the judge. Here are nine misconceptions about the two emperors, debunked:

Fiscal responsibility and insanity tend to be mutually exclusive characteristics. So, if it’s true that Emperor Caligula spent the entire Roman treasury in his four year reign (A.D. 37-41) that’d be a strong point against his sanity.

Caligula—like most men in their early twenties—enjoyed a nice orgy every now and then. Despite a marked increase in games, festivals, and circuses—as well as several ancient sources which claim that Caligula bankrupted one of history’s wealthiest empires—less biased evidence tells a different story.

Right up until the moment he died, Caligula’s government minted large amounts of gold and silver coins. And Caligula’s body wasn’t even cold before his successor, Claudius, began a host of expensive projects and social spending that would have been impossible without the full treasury Caligula had helped to provide. Claudius constructed new aqueducts, began building a huge artificial harbor at Ostia, invaded Britain, and continued to provide gladiatorial games and shows. And he did this without raising taxes, and after paying some of the largest donatives (bribes to bodyguards) ever. So it’s very possible that all of this was funded by Caligula’s knack for building up the treasury.

Guilty as charged—but this is a case where a little context makes all the difference. For most of us, “mom” is the sweet woman who heated Chef Boyardee for us, helped us with homework, and took us to basketball practice. For Nero, however, “mom” was Agrippina the Younger—who married her uncle, plotted against her own family, and murdered as she saw fit in order to clear a path to the throne for the son whom she planned to use as a puppet.

Nero ascended the throne at the rather impressionable age of sixteen, and Agrippina would have ruled through him if her influence hadn’t been blunted by Nero’s famous tutor, Seneca. Thanks to the philosopher’s influence, Nero’s first years as emperor were marked by reason and sound judgment. But having lost her power, Agrippina grew bitter, and plotted against her son. In an effort to discredit Nero in the eyes of the soldiers and common Romans, Agrippina claimed an incestuous union with Nero.

Agrippina’s meddling in both Nero’s personal affairs and those of the empire, reflected poorly on young Nero. And it seems likely that even Nero’s rational advisor Seneca agreed, however reluctantly, that Agrippina must be removed. An attempt to pass the murder off as an accident failed, and eventually a centurion acting on Nero’s calculated order ended Agrippina’s life with a sword.

Based on the experience of Caligula’s successor, Claudius, it’s safe to assume that Caligula left the Roman treasury in good shape. Claims of unfair Scrooge-like taxes are most likely anachronistic. Aristocrats like Suetonius—writing decades after Caligula’s reign—describe taxes that placed an absurd burden on average Romans. But the reality was quite likely the opposite of that.

Caligula was in fact most popular with the masses of ordinary Romans. The emperor’s bravado endeared him to much of Rome—with the chief exception being the senatorial class (who also happened to be the ones getting taxed). And those gents authored the books which have determined our own conceptions of Ancient Rome today.

This helps to explain some strange inconsistencies, such as the Roman people demanding an investigation of Caligula’s murder, rather than celebrating the demise of such a cruel, money-grubbing tyrant. Caligula did his best to court popular opinion, which meant that there were fairly moderate taxes—more than a few of which his successors made permanent via law.

First of all, it would have been impossible for Nero to play an instrument that didn’t exist—and even more importantly, he probably wasn’t even in the city when the fire occurred. The ancient accounts all disagree about whether or not Nero even sang.

For all we know, the theater-loving emperor may have been attempting to mourn through song, rather than speech. This theory makes more sense when we consider that upon his return, Nero organized a massive relief effort and enacted stringent building regulations to prevent another week-long fire from ever devastating Rome again. Nero commissioned numerous public works with the aim of restoring Rome. Even the historian Tacitus—a powerful foe of Nero—admits that the “new” Rome was an improvement over the previous one.

Of course, the grandiose Roman palace Nero started building shortly after the fire overshadowed any goodwill the emperor’s generosity and foresight had garnered. Had he built the domus aurea literally anywhere else or perhaps at any other time, he might have escaped the widespread criticism and dissent which followed.

To modern eyes, Caligula’s intimate relationship with his sister is clear evidence of his depravity. But some parts of the ancient world operated with a different set of social customs, especially for royalty.

It’s easy to forget both imperial Rome’s—and Caligula’s—youth at this time. Rome still wasn’t accustomed to absolutist rule, and Caligula had scant precedent to draw upon. There’s significant evidence indicating that the young emperor was heavily influenced by Hellenistic and Near Eastern kingdoms—places where absolutist rule was common, and bloodlines were often preserved via incestuous marriages.

Part of Caligula’s popular appeal lay in his Julian heritage. Certainly, Caligula was a sexual adventurer, but his relationship with his sister would have been motivated—at least in part—by an effort to keep the Julian lineage pure, and to produce an indisputable successor. Of course, “going eastern” offended pretty much every Roman sensibility; Caligula knew this, yet stubbornly continued to flaunt his own preferences by building statues of his sister.

Before we label Nero a bloodthirsty murderer, it should be noted that he began his rule by banning capital punishment, and doing one thing that truly was crazy for the time—not killing senators like flies. Unlike his predecessors, for much of his rule Nero didn’t make use of intimidation tactics such as secret trials and executions.

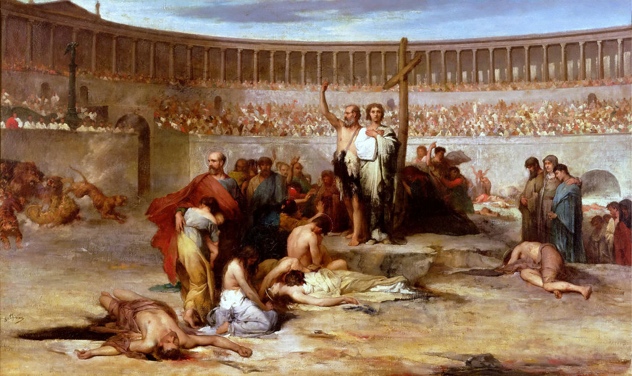

Opposition to Nero’s rule mostly went ignored. Instead of executing them, the emperor seems to have shrugged off lampooners and satirists. But following the Great Fire, all of that changed. In an effort to rehabilitate his approval ratings, Nero pegged the burgeoning Christian movement as scapegoats.

To the Romans, the Christian movement was just another cult—a treasonous cult which already operated in violation of multiple Roman laws. Romans were already suspicious of any religion other than those the state had approved, and they readily accepted the Christians as a threat to the state. The persecutions that followed were cruel, but not without precedent—and they’re more suggestive of canny political maneuvering than genuine insanity.

Here’s another famous one—and something like it really did almost happen. But in reality, Caligula didn’t make his horse consul after losing his mind; rather, he wanted to express his growing feeling that the senators who kept pestering him were about as intelligent as horses.

We’ve debunked this myth here before, but there’s more to the story than the fact that Caligula’s horse never actually became consul. Many scholars believe that Caligula did promise to elevate his horse to what was formerly the highest position in government—but only as a cynical joke.

Rome, especially its aristocracy, liked to pretend that it wasn’t an absolutist state—and so it maintained all the pomp and pretense of the old republican government. Caligula, as we’ve made clear, flaunted his power in pretty much every way possible. Several sources describe Caligula as having a somewhat cruel and mocking sense of humor, which is pretty much to be expected from an average twenty-four-year-old. When Caligula promised to make his horse consul, he was effectively reminding his future biographers that their careers, social positions, and very existence were essentially meaningless, and dependent solely on the emperor’s will. It’s quite possible that not many people laughed at his joke.

The story goes like this: Nero’s depravity alienated Rome and its armies, who threw their support behind a general, Galba, forcing Nero to flee the city—after which he committed suicide.

Nero did engage in some cruel and unusual behavior—especially towards the end of his reign—but even his most unbecoming theatrics didn’t seem to affect the army’s support. Nero’s undoing stemmed primarily from the fact that he was a feckless and ultimately cowardly ruler. Nero fled Rome in A.D. 68 based essentially on rumors of a provincial uprising. Despite their emperor’s cowardice, the frontier legions defeated the uprising, and remained loyal until left with no other alternative.

Originally, it was the usurper Galba who was declared a public enemy. Not until Nero fled the capital and abandoned his position, did the Senate declare Nero an enemy of Rome and elevate Galba to emperor. By the time Nero committed suicide outside the city, the former emperor had himself forsaken the empire as thoroughly as the Senate, Praetorian Guard, and citizenry had abandoned him.

The ancient sources make a lot of claims, and the surviving accounts paint dire pictures of both Caligula’s and Nero’s reigns. But it causes problems when we only use literary sources to determine the nature of an emperor’s rule and character.

Before either deposed emperor’s body was cold, the successor needed to manipulate the narrative of his predecessor’s reign. If the dead emperor had been a monster, then of course it made sense that he should meet an untimely end. The need for successive emperors to distinguish themselves from others who met violent ends likely accounts for some of the hostility in early sources.

Trying to form an accurate picture of Rome’s “bad boys” gets especially difficult when the primary literature uses the word “insanity”, not to indicate that a man is foaming at the mouth, but that he is tyrannical. For instance, the writer Seneca describes Caligula’s ambition and megalomania as insane. What less people know is that Seneca also describes Alexander the Great in the same fashion.

The biggest problem is that our surviving sources are often only consistent in their hostility—and few of them were written when either Caligula or Nero were still alive. What’s really concerning is that the the most outlandish claims tend to appear in literature which was written a very long time after the emperors’ deaths.

It’s like a game of “telephone” spread out over hundreds of years. Imagine if, two thousand years from now, people tried to assemble a record of the Obama presidency based solely on invective Fox News broadcasts from the likes of Glenn Beck—it’d be a fairly one-sided account.