Humans

Humans  Humans

Humans  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptions That Brought Popular Songs to Life

Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Who's Behind Listverse?

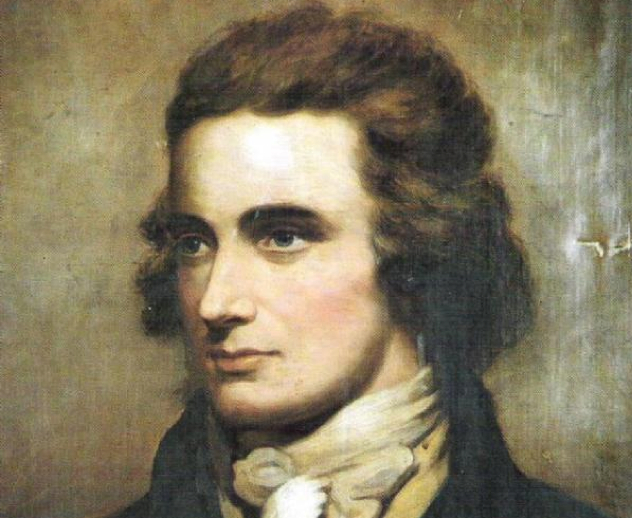

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptions That Brought Popular Songs to Life

Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

8 Worst Journeys Ever Undertaken

We’ve all had “that” journey: the one which saw us miss our flight, get snowed in somewhere in Delaware, and which ended up with us being forced to spend the night warming ourselves with a cigarette lighter. But no matter how awful our worst journeys might have been, they just don’t compare with the following eight trips from hell. You may say that missing Christmas with your family “killed you”—but at least that wasn’t literal. The same cannot be said of:

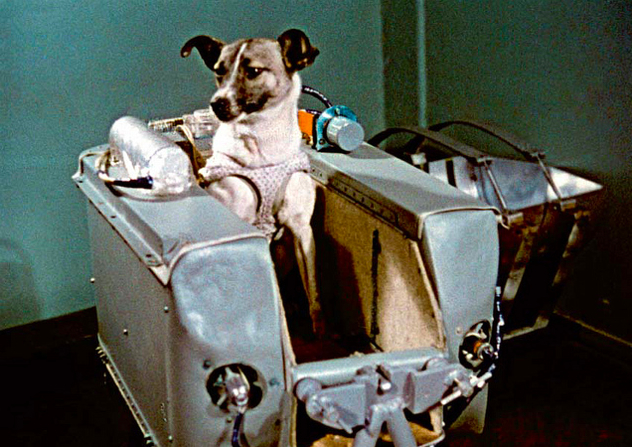

In late 1957, the Soviets needed a snappy follow-up to Sputnik. Given thirty days by the Kremlin to come up with something impressive, or else to get packing for Siberia, Russian scientists decided to do the only logical thing: send a stray dog into space.

On October 31 that year, “Laika” was placed into a narrow rocket and left on a frozen launching pad for three days. In all likelihood, this was the highlight of her trip; the actual lift-off subjected her to enough G-Force to push her heart rate into the ‘danger’ area. At the same time, a malfunction caused the rocket’s thermal control system to shut down, essentially turning the cabin into the space-borne equivalent of a sealed car in a sun-baked parking lot. Within five hours, Laika had become both the first creature to reach orbit, and the first creature to die in orbit: a bitter consolation prize rendered even worse by her patent inability to understand it.

During the Winter of 1719, Swedish Lieutenant-General Carl Gustaf Armfeldt was stuck in Norway with 6,000 battle-weary soldiers. In a desperate attempt to make it home, Armfeldt ordered his men back across the Tydal Mountain range—a useful shortcut into Sweden, provided it isn’t midwinter and your troops aren’t carrying summer equipment.

What followed was one of the biggest logistical screw-ups in military history: the first leg of the journey saw two hundred men die of exposure as the army scrambled for shelter in a tiny village. Rather than be put off by the screaming agony all around him, Armfeldt decided that the best course was to carry on—right into the heart of a blizzard.

In the horror that followed, frostbite set in, horses perished, equipment was burnt for warmth, and wolves descended on hapless victims. By the time the remnants of the army had finally reached Sweden on January 15, nearly four thousand men were dead, with another six hundred maimed for life. Because life laughs in the face of justice, Armfeldt was “punished” for his incompetence with a massive promotion.

Burke and Wills were the Laurel and Hardy of exploration. Tasked in 1860 with finding a land route from Melbourne to Australia’s north coast, the duo set out with such ‘essential’ supplies as 1,500 pounds (680kg) of sugar, a filing cabinet, a heavy wooden table and matching chairs, and a giant gong. In normal circumstances, you’d like to think that God would have taken pity on their amusing incompetence. But Victorian Australia was not “normal circumstances.”

Having timed their trip to coincide with a blisteringly hot summer, the two quickly ran out of supplies, temper, and luck. The original party splintered, with mass-desertions leading to Burke and Wills running for the coast almost entirely by themselves. When they finally got there, their goal was obscured by miles of mangrove swamps – meaning they technically failed, as well as dying in the process. A year or so after setting out, the two explorers expired over ninety miles (145km) from safety, having accomplished nothing and wasted £60,000 of public money in their very successful suicide attempt.

Any trip that ends with you eating a significant proportion of your loved ones is never going to wind up on a list of “10 Loveliest Journeys.” But did you know the Donner trip was awful even before the cannibalism began?

It’s true: the party had every sign of being totally doomed from the start. For one thing, the guy they were meant to be following across the brand new trail turned out to be a fruitcake. Rather than guide them through the mountains, he left letters tacked to trees and generally led them into areas so dangerous you’d swear it was an assassination attempt. This included the Great Salt Lake Desert—an area of the world so inhospitable that even the Elder Gods fear it. Unsurprisingly, this slowed them down.

Secondly, local native tribes decided to start killing their animals like crazy—an inconvenience made worse by the simmering tensions within the group. This leads nicely to number three: they all hated each other. No kidding: two members of the group even had a whip/knife duel at one point. With that sort of animosity, the cannibalism was probably something of a relief.

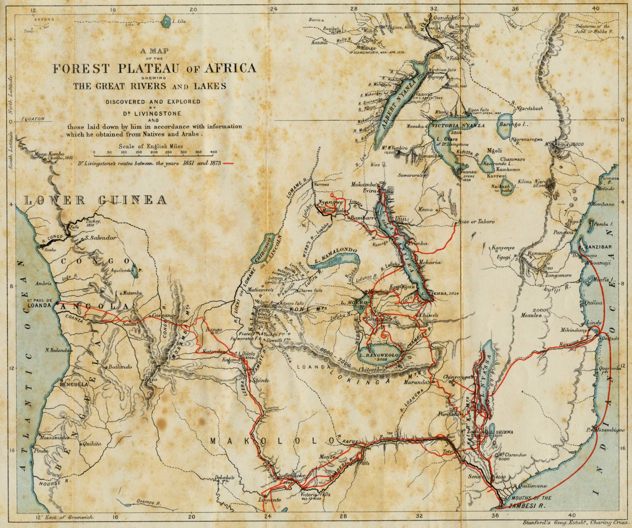

We all know the phrase “Doctor Livingstone, I presume?” But what you probably didn’t know was the full extent of misery Livingstone had undergone before he heard it.

In 1866, Livingstone became determined to find the source of the Nile. How determined? Well, he leapt in a boat for Africa, leaving everything he loved behind, and vanished for six years—eventually resurfacing up as the comical “pet” of a local tribe. And he really was something like their pet: despite the fact that he was riddled with dysentery, suffering from malaria, and bleeding internally, the tribe who found him would only offer him food on the condition that he eat it in full view, for their amusement. They were certainly amused, falling over themselves with hilarity while watching this stuffy white man scrabble for survival—much as we now watch Bear Grylls sleep inside a camel for cheap kicks.

Those six years didn’t exactly end well, either; shortly after the famous words above were spoken, Livingstone plunged back into the jungle and promptly died—seven years after setting out, and no closer to discovering the source of the Nile.

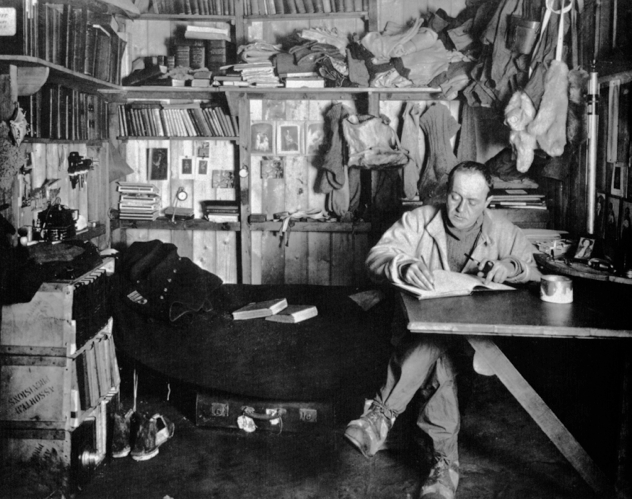

You know those days when nothing goes your way, and life feels hopeless? Well, Robert Falcon Scott had roughly sixty of those—consecutively. They also culminated in his death, which is something we can’t often say about our own bad days.

The year was 1911. No one had yet reached the South Pole, and the race was on to claim it in the name of one or another superpower. In the British corner was Scott: a Navy officer and scientist with some decidedly odd ideas about Antarctic travel. In the Norwegian corner was Amundsen: an expert in cold weather exploration, and one of the greatest explorers of his day.

Despite being clearly fated to lose, Scott made a game effort for the pole: by which I mean he wasted days collecting rock samples, and arrived five weeks late. The return journey was even worse: the weather reached previously-unrecorded savageness; temperatures dropped so low that the snow became like sand; and an unprecedented super-storm pinned down and killed the team just a few miles from safety. In the end, Scott’s pole attempt achieved nothing, killed everyone involved, and made the British look like fools.

Mungo Park was one of the first Europeans to properly explore central Africa. In the process, he managed to set a standard for awful journeys, against which all future disasters could be measured.

Planning to sail down the Niger River and into the Congo (thought at the time to be joined), Park’s expedition was crippled by dysentery even before it reached the river proper. What followed was an exercise in how not to navigate through nineteenth century Africa. Park’s river boat cruised into various territories where it really wasn’t wanted, often resulting in ferocious attacks. Luckily, the Europeans had enough firepower to save their skins—at least until the boat got snagged on a rock.

Thousands of miles from safety, outgunned and outnumbered, Park’s crew were massacre by arrows, leaving Park no choice but to jump into the rushing river. Unsurprisingly, this resulted in his immediate death by drowning—a fact which sadly escaped his son, who died on an expedition to rescue his father some eleven years later.

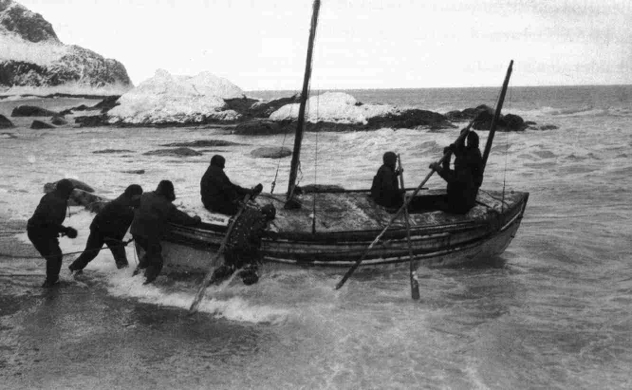

This is it: the granddaddy of all nightmare journeys. In 1914, Ernest Shackleton set off for Antarctica. Before long, his ship became trapped in pack ice, which forced the crew to make a perilous journey across the ice to the only solid ground for miles: a desolate lump of rock called Elephant Island. And that’s when shit got real.

With no other options, Shackleton organized a desperate expedition to the island of South Georgia: eight hundred miles north, across storm-lashed seas. Not your ordinary storm-lashed seas, either: Shackleton reported waves bigger than any he’d seen in two decades of sailing. Ice gripped the boat and sea-spray drenched the occupants, and sleep was impossible. It took fourteen days to reach their destination—and the journey wasn’t over yet.

Thanks to the unfavorable ocean currents, the team was forced to land on the wrong side. Since it was impossible to sail round to safety, they were forced to cross the harsh interior on foot, without maps, more or less navigating through guesswork. After fighting their way for three days through thick fog over mountains, they finally reached humanity—at which point Shackleton very nearly slipped and fell to his death. But he didn’t, and here we come to the uplifting bit: everyone survived. In the face of the harshest conditions on Earth, Shackleton managed to keep every single one of his men alive and to bring them home. So remember that next time you’re having the “journey from hell.”