Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

10 Unusual Ways People Solved Difficult Problems

You know what they say: necessity is the mother of all invention. So, what do you do when you need a solution to a fiendishly-difficult problem? Simple. You get fiendishly inventive, just like these guys did.

Hiding within the desolate highlands of Northern Scotland is the site of Dounreay. Since the 1950s, it’s served as the home for several nuclear research facilities, most of which are now in the process of being decommissioned by the UK Government. As you can imagine, this isn’t the easiest of jobs; however, one facility was proving more troublesome than the others: namely, an experimental chemical plant built to recycle plutonium liquor, a process which involved running highly-radioactive liquids through hundreds of pipes and vessels. Each of these was covered in a thick layer of plutonium stains, providing an immense health hazard for the clean-up crew.

But, whilst watching TV one day, one team-member saw an advert for Cillit Bang, a brand of household cleaner renowned in the UK for being able to remove most types of dirt and staining. At their wits end, the team tested it out, only to discover to their surprise that it worked much better and faster than the expensive cleaning solution they were using originally. As well as this, they noticed that the contamination levels of each component dropped significantly after being cleaned with Cillit Bang, so much so that other nuclear sites in Britain have expressed an interest in using the product during the decommissioning of their facilities.

In order to ensure that penguins aren’t destined to become extinct, scientists need to regularly monitor population movements. However, whilst this wouldn’t be easy with most animals, it’s even trickier with penguins. Because of a variety of reasons, it’s hard to track them from a plane, whilst the traditional method of using trackers has been found to be having the adverse effect of killing them off.

But, the scientists have had help tracking their movements by…erm…tracking their movements. By making use of high-quality satellite imagery, British scientists have been monitoring the travels of King Penguin groups by looking for tell-tale brown guano marks on the ice, left behind by mating colonies that often spend up to 10 months in the same spot. Using this method, researchers have identified an additional ten colonies of penguin’s previously-unknown to conservationists.

Forgeries within the art world are a major problem. After all, it isn’t exactly uncommon to hear on the news about an art collector who paid millions for a painting purported to be by a great artist, only to later discover that it’s a fake. Statistics are hard to come by regarding the economic damage of this practice (partially because few victims are willing to come forward and admit their expensive mistake), but to get a sense of the scale of the problem, here’s a list of the eight biggest art forgeries ever committed.

Luckily, in the fight against forgeries, there’s a new weapon: nuclear fallout. After the first nuclear tests in 1945 (prior to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki), two isotopes—hitherto unknown to nature—were released into the atmosphere: caesium-137 and strontium-90. These isotopes soon found their way into plants which were then used to create paints. According to the scientists who came up with this idea, if any paintings claiming to have been painted prior to 1945 are found via testing to use paints which contain caesium-137 and strontium-90, there’s a high probability that it’s a forgery.

To say that Israel is somewhat unpopular in the Middle East would be a huge understatement. So, following the Six Day War (fought in 1967 against the forces of Egypt, Jordan, and Syria), the country ordered the construction of a massive defensive line bordering the Eastern coast of the Suez Canal, in order to defend against any future attacks by Egypt. The primary feature of this line was a 20-25 meter tall wall of sand which spanned the entire length of the line. With this in place, it was thought to be impossible to land any surprise landing parties on the shoreline, so much so that Israeli engineers estimated that it would take any attackers 24+ hours to breach the sand wall.

However, in 1971, an Egyptian officer came up with a solution: by using a water pump attached to a cannon, it would be possible to liquefy and blast the sand away, leaving a gaping hole in the defensive line. The plan was approved and over the next several years, Egypt bought hundreds of pumps in anticipation for the conflict that was to be the Yom Kippur War of 1973. By launching a surprise attack, Egyptian forces were able to breach the Bar Lev in less than two hours. Over the next day, 81 breaches were made by this method, resulting in the removal of over 3,000,000 cubic meters of sand.

The ‘Night Witches’ was the nickname given by the Germans to the members of the 588th Air Regiment, a night bomber division of the Soviet air force that comprised exclusively of female pilots. Between 1942 and 1945, the group flew numerous bombing missions against the enemy using old Polikarpov U-2 biplanes (made in 1928); however, the small size of the aircraft meant that it was only capable of holding two bombs at a time, so each plane would have to do numerous bombing runs per night. Alongside this, the planes were also ridiculously slow, meaning that if one got caught in the spotlight of a searchlight, the Germans could easily shoot it down with anti-aircraft guns.

Therefore, in order to maintain the element of surprise (and not die), the Night Witches devised a near-suicidal strategy: when the pilot was approaching a target, they would simply cut the engine in mid-air. Without the noise of the engine and propellers, the plane was able to silently glide down, and then restart its engines and drop its bombs before it was too late to be stopped. When working in pairs, some pilots would also make use of this technique by having one plane approach the target noisily, whilst another would be silently gliding to the target and taking advantage of the distracted enemy forces.

In the 1990s, Houston Airport was being besieged with complaints about the amount of time that passengers had to wait to retrieve their bags from the baggage claim. Several years before, they’d tried to solve this problem by hiring extra staff to manage the transfer of baggage, all to no avail. Despite the wait time being brought to within the industry standard of eight minutes, the complaints persisted.

Eventually, the frustrated management hit on a simple solution: move the baggage claim hall further away from the terminals. An analysis of the airport’s layout showed that it only took an average of one minute for passengers to travel from the planes to the baggage claim, nowhere near enough time for the baggage handlers to unload the plane. Passengers now had to walk six times longer to retrieve their luggage, which reduced the amount of time they were waiting once they got there. Underhanded? Maybe. Devilishly clever? Yes.

By all accounts, one of the worst things that soldiers face nowadays is the threat of Improvised Explosive Devices, or IEDs. Insurgent groups frequently build these from any explosive materials that they can find (such as artillery shells and grenades) and place them in locations that they know enemy forces will need to visit. Although most are deployed at roadsides, some are used in houses to kill forces engaged in searching homes for enemies and weapons caches. In this latter example, the enemy attaches the explosives to a simple tripwire, which is then strung across a doorway, in the hope that no-one will notice it until it’s too late.

But, forces in Afghanistan and Iraq have since devised a technique to make sure that doorways don’t contain these deadly traps: spraying the length of the doorway with silly string. The lightness of the silly string ensures that if it snags on a tripwire, it won’t set off the explosives, thus alerting soldiers to the tripwire’s presence. However, as silly string isn’t standard-issue equipment, most of the 100,000 cans of silly string that have been deployed overseas are the result of relentless collection drives by one woman, Marcelle Shriver.

Over sixty years ago, a US military cargo shipment arrived on the island of Guam carrying supplies and an unexpected stowaway: a Brown Tree Snake. Although that might not seem like a disaster, for the island of Guam it was. The snakes reproduced at a seemingly-exponential level and, because the island wasn’t host to any predators of this snake, they were able to thrive unhindered. As a result of their arrival, several species of animal and bird unique to Guam have been rendered extinct, the populace suffer regularly from power outages caused by snakes interfering with the power cables, and the military has been forced to screen each flight off the island in the hope of preventing the snakes from invading any other islands in the South Pacific.

But in 2012, scientists starting back against this plague. How? By attaching parachutes to mice corpses, poisoning the bodies with the pain-relieving chemical acetaminophen, and airdropping them all across the island. The idea is that the snakes would eat the mice and, thanks to the effects of the drug, fall into a coma and die. It might sound like an idea out of a Tom and Jerry episode, but strangely it appears to be working. However, the aim of this project isn’t to eradicate the species entirely, only reduce their numbers to a level that’s somewhere near controllable.

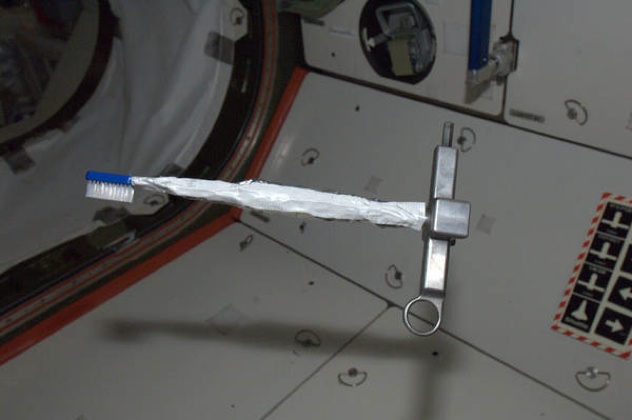

No matter how much futuristic gadgetry we stock our spacecraft with, things will always go wrong in a spectacular way. Take, for instance, the recent disaster on-board the International Space Station; one of the four units responsible for distributing power from the station’s solar panels failed, leaving the station with ¼ less power. The crew on-board donned spacesuits and attempted to fix the problem using some of the aforementioned gadgetry, however, they ran into a problem. Metal shavings had accumulated around the bolt attaching the broken unit to the station, making it near-impossible to detach and replace the unit.

But, days later, the crew unveiled their solution: they had attached a $3 toothbrush to a metal pole and, using this alongside a can of nitrogen gas, they were able to scrub away the majority of the shavings, thus allowing the faulty unit to be replaced with as much ease as is possible whilst floating around in space. And, just in case you were wondering, no astronauts had to suffer poor dental hygiene as a result of this: NASA later confirmed that the toothbrush was a spare.

During WW2, Germany waged a massive bombing against Great Britain, in a vain attempt to destroy both the Royal Air Force and the country’s will to fight, thus clearing the way for an invasion. One of the planes used by the Luftwaffe was the Dornier 17, a medium-range bomber with all the maneuverability and speed of a jet fighter. Despite a force numbering in its hundreds, however, it was thought that no Dornier 17’s survived the war. That is, until one was found buried in a sandbank by a diver off the coast of south-east England. However, the plane was built with aluminum, a material which corrodes badly in sea water. Without a solution, should the team be able to get it out of the water, it was unlikely that it would last even a short time before falling apart.

Scientists at the Imperial College London, however, have figured out a way to halt the seawater’s corrosive effects: using lemon juice and water. After testing this mixture on a small piece of plane already salvaged, the mixture was found to be capable of both cleaning the metal and halting the damage of the seawater. So, as a result, after carefully retrieving the plane from the bottom of the ocean using a crane and barge—a process which’ll take approximately 4 weeks—the two main pieces of the plane will be stored in two tunnels where they’ll be blasted with this lemon juice mixture for 8 hours a day for 18 months, until such a time that it’s stable enough to be placed on display.

If you want to read more from Adam, you can check out his website, One Word Louder, or follow him on Twitter.