Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Amazing Forgotten Explorers

Sometimes it’s not enough to be the first, to go the farthest, or even to chart the uncharted. Historical memory can be a fickle mistress, which is why we’ve decided to right historical injustice and celebrate the oft-overlooked pioneers of exploration.

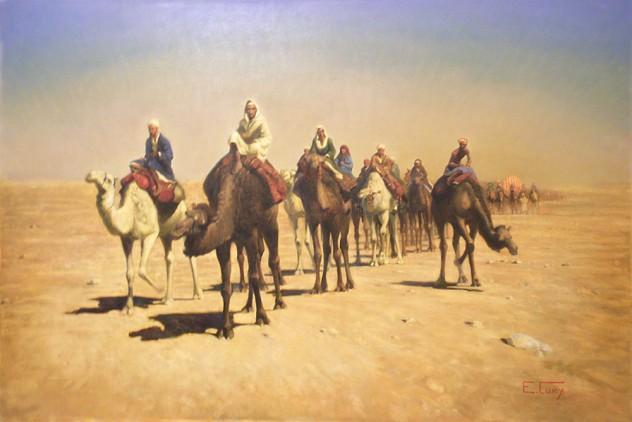

10 Alexander Gordon Laing

1793–1826

For late 18th– and early 19th–century Europeans, Timbuktu was the El Dorado of Africa. But there’s a reason the word “Timbuktu” is still synonymous with remote isolation, because even if Alexander Laing could have accessed Google Maps it wouldn’t have done him any good.

With only a vague idea of where he was heading, the British army officer and his tiny retinue left Tripoli in July 1825. Laing’s local guide promised the plucky Scotsman the journey would take only a few weeks, but the caravan spent 13 months wandering the desert, avoiding warring nomads, and fighting its own war with thirst and hunger.

The worst of Laing’s ordeal came 1,600 kilometers (1,000 mi) and nearly a year into his journey, when his guide betrayed him to bandits. Laing survived and recounted the event like a minor inconvenience akin to burnt chips in a letter to his father-in-law. After detailing multiple cuts and fractures all over his face, head, and neck, he concludes: “I am nevertheless, as already I have said, doing well.”

Laing stumbled into Timbuktu a couple months afterward. He and his journal disappeared, but his subsequent murder was confirmed in 1828 by the second European explorer to reach the city.

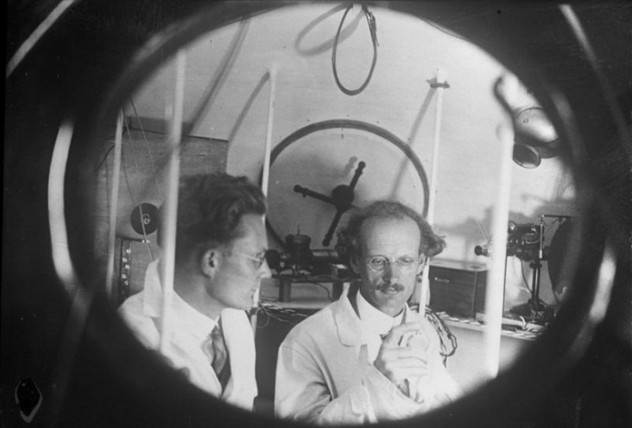

9 Auguste Piccard

1884–1962

The Swiss scientist began his career as a physicist working with Albert Einstein and may have looked more science-y than any other man in history. But the two brilliant scientists’ paths diverged as Piccard became fascinated with the study of cosmic rays.

Of course, the Earth’s atmosphere interfered with Piccard’s study of said rays. His solution? Leave the atmosphere. To accomplish this and further his research, Piccard built a balloon complete with an attached pressurized chamber. And over the course of more than two dozen balloon flights, Piccard reached altitudes ranging from 15,000 to 23,000 meters (50,000 to 75,000 ft)—higher than any man before him.

8 Zhang Qian

200–114 B.C.

In the second century B.C., the Chinese weren’t too sure of what lay west of them. So the Han government commissioned its envoy, Zhang Qian, to locate Central Asian kingdoms and open up new markets for Chinese exports.

Qian made it as far as Bactria (Afghanistan) where he encountered the remnants of a fascinating culture that had been forced south into India by nomads. The Greco-Bactrians were Hellenic colonists who settled in the area following Alexander the Great’s conquests. They brought grapevine cultivation, European horses, and traditionally proficient artists to the area—which Qian reported to the Han court.

But Qian wasn’t done yet. Despite the occasional kidnappings by Xiognu nomads, Qian continued to crisscross the Central Asian steppe and frequently saw Chinese goods, like silk, command outrageous prices. Qian forged trade agreements with countless peoples as he traveled. And within about a decade of Qian’s death, Chinese traders were regularly traveling between the continents to exchange goods along routes similar to Qian’s. Those routes formed one of history’s greatest networks of commercial exchange, the Silk Road.

7 Pytheas

4th Century B.C.

A Greek sailor, Pytheas, discovered—at least from a Mediterranean perspective—the British Isles. Pytheas circumnavigated Britain at a time when most Greco-Roman minds imagined little existed beyond the Pillars of Hercules (Gibraltar) other than an endless ocean.

Before Pytheas could even begin his exploration in earnest, the Greek geographer had to navigate the Carthaginian blockade at modern-day Gibraltar. Apparently, Pytheas managed to avoid Carthage’s warships and sight Britain, Scotland, and Ireland.

But the most incredible part of Pytheas’ expedition came when he found a land he called Thule. Lying one week’s sail north of Britain, Thule, as described by Pytheas, was a place where oceans “congealed” and days lasted only a few hours. While his findings sounded laughable to ancient scholars, Pytheas’ voyage probably traced part of Norway’s Atlantic coast and likely took the Greek ship into the Arctic circle (the “congealing oceans” obviously being ice), making Pytheas history’s first polar explorer.

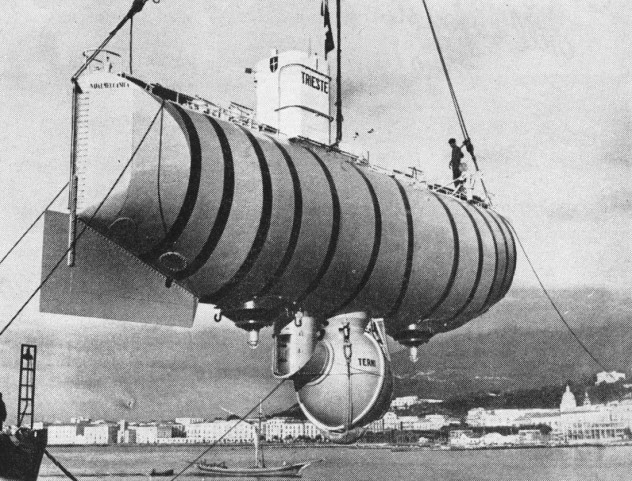

6 Even More Auguste Piccard

1884–1962

Auguste Piccard was no one-hit wonder, hence his place here twice. We just couldn’t keep him off the list with all the records he’s broken. Being the first man to enter the stratosphere was only the beginning for him. After World War II ended and funding to match his ambition became available, Piccard pursued his next dream—deep-sea exploration.

Piccard invented a steel-hulled submersible he dubbed a “bathyscaphe.” Piccard’s third bathyscaphe, The Trieste, resembled his high-altitude balloon design in reverse. The Trieste‘s cabin was built to withstand pressures exceeding 16,000 lbs per square inch—more than enough to flatten the average submarine. With US backing, Piccard’s son, Jacques and Don Walsh, a US naval officer, piloted The Trieste to the deepest point on the Earth’s surface, the floor of the Mariana Trench. This achievement was not duplicated for half of a century.

5 Ibn Battuta

1304–1368

Ibn Battuta, a son of middle-class Moroccan parents, was all set to become a lawyer and lead a traditional life. Then a pilgrimage to Mecca intervened. Once Battuta got there though, he pulled a Forrest Gump and kept running—or in this case, riding his horse.

After reaching Mecca, Battuta continued on to Persia and then back to Baghdad. Ibn Battuta then determined that he would go as far as possible as often as possible while “never traveling the same route twice.” For the next three decades, Ibn Battuta kept to his motto almost continuously and covered 120,000 kilometers (75,000 mi), a feat unequaled for centuries.

Actually tracing all of the traveler’s routes means grabbing a map of Europe, Africa, and Asia, then marking it with enough ragged pen lines to begin rendering it incomprehensible. For most of his travels, Battuta traveled within the Muslim world. His insider status allowed him privileged access to and observation of the customs of far-flung peoples, which he recounted (not always entirely accurately) in The Travels of Ibn Battuta.

4 Hanno The Navigator

6th Century B.C.

To be fair, Hanno has not been completely forgotten; the Carthaginian sea-captain and original “Navigator” is the titular inspiration for a 2008 song. Long before Pytheas journeyed through the Pillars of Hercules and north, Hanno made his way south along the West African coast.

Whereas several explorers are notable for their solo efforts, Hanno amazes with the incredible scale of his undertaking. Hanno’s fleet consisted of 60 ships and 30,000 men and women. Hanno wasn’t merely exploring; he was colonizing. And to that end he was successful: the Carthaginians established several lasting towns and trading posts.

Unfortunately, dwindling provisions forced Hanno to abandon his attempt at circumnavigating Africa. However, Hanno’s account did leave scholars with several intriguing references to African geography and animals, like the following:

“Most of them were women with hairy bodies, whom our interpreters called ‘gorillas’ . . . we could not catch any males: they all escaped . . . However, we caught three women, who refused to follow those who carried them off, biting and clawing them. So we killed and flayed them and brought their skins back to Carthage.”

So, Jane Goodall wouldn’t be proud, but the earliest probable reference to the large primates? Maybe add “The Zoologist” to Hanno’s honorifics.

3 Harkhuf

Approx. 2280 B.C.

Over 4,000 years before Stanley presumed anyone to be Livingstone, the Egyptian courtier Harkhuf was busy exploring the vast interior of Africa. During the 23rd century B.C., Harkhuf led four expeditions into lands far removed from the Nile riverbank.

It’s believed that Harkhuf carried Egyptian influence as far as the Kingdom of Yam (possibly modern-day Chad) and Sudan. The journey to the former would have taken the explorer through hundreds of miles of unforgiving desert (on foot), and perhaps even farther, as Harkhuf’s tomb inscription notes as a point of pride that the trek took only “seven months.”

Harkhuf’s funerary inscription also suggests the Egyptian explorer encountered a pygmy tribe in his travels. That same inscription makes Harkhuf the first explorer (of the imperial variety) in all of recorded history. Not the first explorer to “cross” or “circumnavigate” or “discover”—the first explorer of written record. Ever.

2 Juan Sebastian Elcano

1476–1526

Trivia fans and Listverse readers probably know Magellan was killed well before he could complete the first circumnavigation of the world. Far fewer know the lengths his successor went to in finishing the last 16 months (or nearly half) of the voyage.

Sure, Juan Sebastian Elcano was a mutineer, but to be fair, after almost a year of searching, Magellan’s expedition still hadn’t found its way around South America, and the Spice Islands could never have seemed farther away. Considering only 18 of Magellan’s 240 men actually made it back to Spain, maybe Juan Sebastian had reason to be worried.

By the time Elcano assumed command following Magellan’s death in the Battle of Mactan, only half the crew remained. And since Magellan had renounced his Portuguese citizenship to sail for the Spanish, Elcano and his ship, Victoria, were considered pirates within Portuguese waters—which was pretty much the entire Indian Ocean.

Preferring starvation to probable execution, Elcano crossed the Indian Ocean without putting into port. Thanks to this feat of seamanship and Elcano’s grim determination to avoid capture, one-third of his crew completed the circumnavigation, returning to Spain in truly ghastly shape—but alive nonetheless.

1 James Holman

1786–1857

When Holman died in 1857, he was perhaps the most well-traveled man the world had ever seen, having logged some 400,000 kilometers (250,000 mi) in his lifetime. Holman hadn’t planned on being a professional globetrotter and author; he originally aspired to be a British naval captain, but a sudden illness at age 25 robbed him of his sight.

Undaunted, Holman spent the entirety of his life seeking out new experiences in exotic lands. “The Blind Traveler,” as he became known, bucked cultural conventions, rejected travel companions, and refused to be treated as an invalid. Holman first crisscrossed Europe then attempted a mostly overland circumnavigation of the world—an attempt cut short when Russian authorities suspected him of actually being sighted and spying for Great Britain.

Unfortunately, little documentation exists of Holman’s actual routes over the next two decades, when he did the bulk of his traveling across Eurasia and Africa. Even so, plenty of evidence remains of the man’s adventures, like his ascent of Mount Vesuvius while it was erupting or his hunt of a mad elephant in Ceylon. Sadly, Holman’s writing and travel were victims of the era’s prejudice. The 19th-century public refused to believe a blind man could observe the world around him with such insight and depth. And with the exception of leading minds like Charles Darwin and (later) Sir Richard Burton, Holman’s accomplishments were roundly ignored.

Want more J.? You can find him here, force-feeding history down comedy’s gullet.