Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Wartime Mass Suicides

While the idea of one person taking their own life is heartbreaking and confusing enough, the truth is that, in dire situations, it has happened on a mass scale.

10 Pilenai

On February 25, 1336, the castle of Pilenai (now in modern-day Lithuania) was under siege by Teutonic Knights. The castle’s army, led by the Duke Margiris, fought valiantly, but with roughly 4,000 soldiers left defending the walls, the Duke recognized that he could not win the war. Knowing that his subjects would be turned into slaves, he called upon his troops to set the castle alight, destroy all their possessions, and then commit mass suicide.

The opera Pilenai by Vytautas Klova tells the story of the tragic siege.

9Saipan

The battle of the island of Sapian is most remembered as an amazing show of US military defiance, but there was another act of defiance which took place during that bloody battle: mass suicide.

Fearing the US troops would torture and murder them—mainly due to propaganda laid out by the Japanese army—the citizens of Saipan walked into the sea, or jumped off the cliffs and drowned themselves. The most notorious scene of the mass suicide was Marpi Point, a steep 250-meter (800 ft) precipice where American soldiers witnessed entire families fling themselves into the waves. First the older children pushed the younger children over the edge, then the mothers would push the eldest children, and finally the fathers would push their wives, before jumping over the edge themselves. An estimated 22,000 civilians died this way.

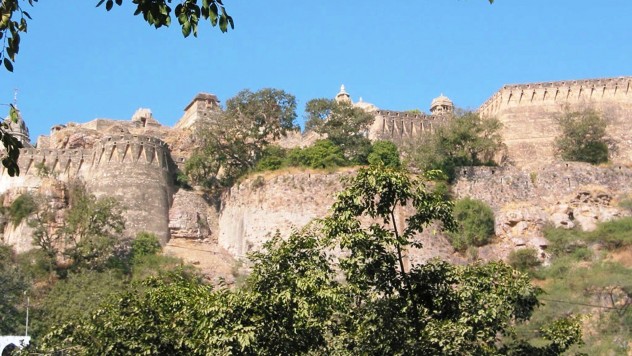

8 The Fort Of Chittorgarh

Jauhar is an old Indian act of mass self-immolation. The act was performed by women and children within the walls of besieged castles or towns when the outcome was in the favor of the enemy. Men didn’t get off scot-free either: In an act known as “shaka,” they would band together and charge into battle one last time to die honorably.

The most famous act of jauhar in Indian history happened in 1303. Chittorgarh was the capital of Rajput and a revered fort. But when Alauddin Khilji lay siege to the fort, he eventually broke down the resistance. His quarry was the beautiful Rajput queen, Rani Padmini of Chittorgarh. But once the battle was won, the queen, rather than fall into Khilji’s hands, committed suicide along with all the other women of Chittorgarh. This wouldn’t be the only siege Chittorgarh would suffer over the years. Another attack occurred in 1535, and yet again in 1567, and both times the fort’s army was defeated and the women and children committed jauhar.

7 Puputan Of Badung

On September 20, 1906, the Dutch army attacked Bali and met little resistance. When they reached the town of Badung, they found that the people there had taken their fate into their own hands. The Balinese royal family had foreseen the arrival of the Dutch and, knowing they were completely outnumbered and their resistance futile, the kings, their families, and hundreds of their followers all took their own lives.

The Balinese ritual of Puputan, which roughly translates into English as “finishing,” required the men and women to stab themselves and their children (from newborns to the eldest) in an act of suicide. Although this is the most famous example of puputan, a series of puputan had taken place throughout Bali in the years leading up to the events at Badung.

6 Teutonic Women

The Teutons were a Germanic tribe banging around the European continent about 200 years before the birth of Christ. “Germanic” was a descriptor given by Greek and Roman authors to any tribe from Northern Europe. Around 100 B.C., the Teutons decided to up sticks and go on a bit of an adventure, migrating south and west, banking on easier land for farming. What they didn’t bank on, however, was bumping into the fast-expanding Roman Empire.

By the time the Tuetons arrived on the border of the Roman colonies, their pillaging had gone before them. Roman general Gaius Marius was there to meet them. Despite a hard-fought Battle of Aquae Sextiae, nearly 90,000 Tuetons were killed and their King Teutobod was taken captive. As a condition of the Teuton’s surrender, Marius ordered the king to hand over 300 married women, whom he intended to give to his Roman men. But the chosen women pleaded with Marius, begging him to release them to do service in the temples of Ceres and Venus. Marius denied them this right, and when the Romans went to wake their women the next morning they found every single one of them dead.

5 The Numantines

Numantia was a small town in the north of Spain. The town existed in the second century B.C. and entered into folklore after an eight-month resistance against a Roman army. The town eventually fell in 133 B.C. to General Scipio Aemilianus.

The Numantines were a proud people and, rather than give up their bodies, they committed mass suicide. But that’s not all: The memory of Numantia was preserved by Miguel de Cervantes, the playwright who penned El cerco de Numancia (“The Destruction of Numantia”) in the 1580s, a play based on the events at Numantia. The story was even used during the Spanish Civil War when both the Republican forces and the Nacionales of Franco adopted the image of Numantia to motivate their followers and promote the idea of death over dishonor.

4 Dance Of Zalongo

The Souliote War of 1803 was a battle between the Souli and the Ottoman-Albanian army. After it become obvious that defeat was unavoidable, the Souli began to evacuate Souliote—but a small group of Souliot women and their children were pinned down in the mountain of Zalongo. In an act which has become known as the Dance of Zalongo, the women threw their children off the cliff first and then followed shortly after. The legend says that they jumped off the cliff singing and dancing.

Many works of art have been based on the event. French artist Ary Scheffer created two paintings, and a monument has stood on the site of Mount Zalongo since 1950 to commemorate the sacrifice. The Dance of Zalongo is also a popular folk song and dance practiced throughout Greece to this day.

3 Demmin

On May 1, 1945, about 1,000 residents of the town of Demmin in Germany committed mass suicide. The event came after the Russian army started to sack the town. Demmin was located between the Peene and Tollense rivers and, once the Russians pushed the Nazis back, the call came from high command to blow the bridges, halting the Russians’ advance but in turn entombing the citizens of Demmin within the city limits without any path of escape. They were stranded, unable to leave the city and cornered by their new Russian invaders.

Survivors of the invasion claimed that once the Russian army had stumbled upon a warehouse of booze, they fell into a rage and began to rape and pillage throughout the town. Anyone who tried to stop the assaults was shot in cold blood. Eventually, the Russians torched the town and two-thirds of the city went up in flames. As the city burned, between 1,200–2,500 Demmins committed suicide—some records even suggesting that mothers threw their children into the freezing waters of the two rivers before jumping in after them.

2 Masada

Masada is a mountain fortress overlooking the Dead Sea. An apt setting if ever there was one, because Masada is the setting of one of the most horrific scenes the world has ever seen. The archaeological dig of Masada in the 1960s is considered the biggest excavation since the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb.

So what’s so special about Masada? In the year A.D. 73, the Jewish community living there was surrounded by a Roman army. In what became known as an astounding act of Jewish defiance, commander of the Masada soldiers Elazar Ben-Yair ordered each man to kill his wife and children before turning their swords on one another—effectively ordering the execution of 960 citizens. Masada has such a place in Jewish folklore that it was still used as the place to swear in new soldiers for the Israeli army until recently.

Considering that this happened 2,000 years ago, facts are sketchy. The first dig took place in 1963–65, conducted by Professor Yigael Yadin—an archaeologist and former chief of staff of the Israeli army. He reported the myth as above: a heroic act denying the Romans victory by sacrificing themselves. But in the 1990s, another dig gave contradictory evidence: Some of the skeletons within the complex were revealed as Roman (they had had their hair sliced from their scalp as was common for captives), and the siege was hypothesized as a six-week affair rather than the year-long standoff that was reported earlier. The fact is, no one will ever truly know what happened, and the Masada myth, to many, will always be a mystery.

1The 47 Ronin

The tale of the 47 Ronin is ingrained in Japanese culture. But unlike the stories of Aesop or the Brothers Grimm, this one is true.

During the Tokugawa era, Japan was ruled by a military official known as a shogun. Beneath the shogun there were several regional lords, called the daimyo, each of whom had a small army of samurai. To be a samurai was to accept the code of bushido or the “way of the warrior”—including, above all else, loyalty to one’s master and a refusal to fear death.

In the year 1701, Emperor Higashiyama (who only held a ceremonial role under the rule of the shogun) sent some envoys from his throne in Kyoto to the shogun’s court in Edo (what is now modern day Tokyo). Kara Yoshinaka, one of the shogun’s officials, oversaw the event, giving two young daimyo (Asano Naganori of Ako and Kamei Sama of Tsumano) the job of looking after the emperor’s envoys.

For unknown reasons, Kira didn’t like Asano and Kamei very much, and bullied them throughout their work. While Kamei never rose to the bait, Asano was a different story. When Kira called Asano a “country bumpkin without manners,” it was the final straw. He drew his sword on the shogun’s official. Kira took a blow to the head, but the fracas was quickly stubbed out. The matter, however, was not over. Asano, having broken strict law by drawing his sword within the Edo palace, was ordered to take his own life in the samurai act known as seppuku: disemboweling oneself with a short blade.

Kira didn’t stop there. He confiscated Asano’s domain, cast out the dead daimyo’s family, and reduced his army of samurai to the status of ronin (“masterless”). Despite the fact that the bushido decrees that masterless samurai should take their own lives due to the dishonor of not protecting their master, 47 of the 320 warriors refused. Instead they exiled themselves, and waited for the perfect time to avenge the death of their master.

Two years later, the ronin gathered and descended upon Kira’s home. In the middle of the night they stormed his manor, killing his 40 guards without a single ronin dying in the battle. They found Kira hiding in a coal shed and ordered him to kill himself with the same blade Asano had committed seppuku with. He refused and the leader of the ronin beheaded Kira then and there.

After the assault, the ronin marched to the nearby Sengakuji Temple where Asano was buried and presented the head of Kira to their fallen master. By now, news of the assault had spread across the land, and the ronin were ordered to kill themselves. They complied, committing mass seppuku right there in the temple.

![11 Lesser-Known Facts About Mass Murderer Jim Jones [Disturbing Content] 11 Lesser-Known Facts About Mass Murderer Jim Jones [Disturbing Content]](https://listverse.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/jonestown2-copy-150x150.jpg)