Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff The 10 Unluckiest Days from Around the World

Food

Food 10 Modern Delicacies That Started as Poverty Rations

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Shared TV Universes You’ve Likely Forgotten About

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 of History’s Greatest Pranks & Hoaxes

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Widespread Historical Myths and the Texts That Started Them

Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff The 10 Unluckiest Days from Around the World

Food

Food 10 Modern Delicacies That Started as Poverty Rations

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Shared TV Universes You’ve Likely Forgotten About

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 of History’s Greatest Pranks & Hoaxes

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Widespread Historical Myths and the Texts That Started Them

Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

10 Sea Creatures That Belong On Another Planet

If you were a movie producer and somebody pitched a film about a tentacled alien that could shape-shift, become invisible, and shoot a blinding cloud of chemicals at its enemies, you’d just sigh and say “No, that’s an octopus.” We take it for granted that there are a few million creatures like that floating around; at some point, science jumped into the back seat of creation and let nightmarish curiosity drive for awhile. But even among the world’s most bizarre creatures, there are extremes.

10 Atolla Jellyfish

Atolla jellyfish are pretty common. They’ve been found in every ocean of the world, but they’re not something you’re likely to come across at the beach because they usually live over 700 meters (2,200 ft) below the surface. Like many deep-sea creatures, they’re bioluminescent (they light up like fireflies). But atollas don’t use their lights to capture prey like anglerfish do—they use them to escape. If an atolla is caught by a predator, it emits a frenzy of bright pulses, like a strobe light. The light show attracts even bigger fish, which will go for the atolla’s attacker, giving it a chance to get away.

The atolla also has a single, elongated tentacle, which it uses to capture prey. They grab their victim with the end of the tentacle and drag the helpless creature through the water, jerking it back and forth until it’s too tired to fight back—like a fisherman reeling in a big fish.

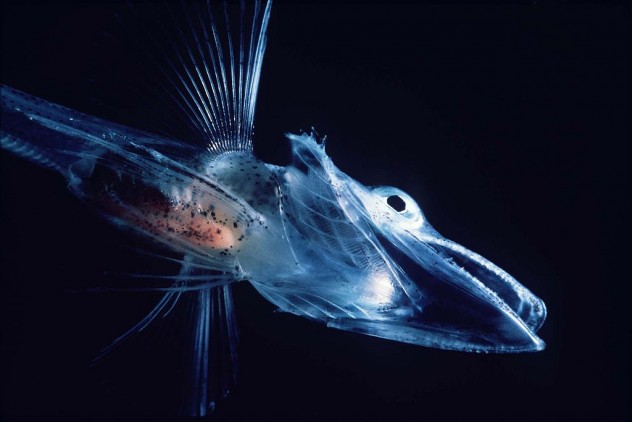

9 Antarctic Ice Fish

Extremophiles (animals that live in extreme conditions) are, as a rule, pretty unusual. But the Antarctic ice fish might take the cake. As the name suggests, they’re found in the deep waters around Antarctica, usually in temperatures lower than 0° C and at depths of up to a kilometer (about 3,300 ft).

They’re completely colorless; even their blood is transparent. They still have blood, but it doesn’t contain any hemoglobin, a protein in red blood cells that transports oxygen and gives blood its redness. They’re the only vertebrate in the world with that characteristic, and researchers are still trying to figure out why the ice fish developed it in the first place. On top of that, their blood contains an antifreeze protein, which prevents their blood and soft tissues from freezing. It’s because of this protein that they can live in sub-zero temperatures without becoming a fishsicle.

8 Emperor Shrimp

The tiny, colorful emperor shrimp looks looks more like a piece of candy than a living thing, but its striking color serves a very important purpose . . . actually, we have no idea why they’re so colorful, despite the fact that they’ve been studied since 1967. It’s possible that they just have no need for camouflage. Emperor shrimp live almost exclusively on the backs of a type of sea slug known as a nudibranch, specifically the Hexabranchus marginatus, which has few predators because it absorbs toxins from its food. There’s really nothing out there that would attack them anyway, so maybe they’re just showing off.

7 Blue Dragon Sea Slug

Most animals eat animals that are smaller than them. It’s just the way the world works. The blue dragon, on the other hand, laughs in the face of reason and goes straight for the biggest, most dangerous creatures it can find—like the Portuguese man o’ war, and if none of those are around, other blue dragons. By eating the tentacles of the man o’ war, blue dragons absorb the stinging cnidocyte cells, which they store in sacs in their bodies to use in self-defense if they’re attacked.

But it gets weirder. Most sea slugs crawl along the bottom of the ocean. Blue dragons? They swallow an air bubble and float just under the surface of the water. When viewed from below against the water’s surface, they look something like a spider walking on a mirror. They just float wherever the waves take them, eating anything they run into.

6 Felimare Picta

The Felimare picta is a species of sea slug that lives in warm, subtropical waters, particularly around the Mediterranean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico. There are six different subspecies of Hypselodoris, and they’re actually a subsection of the nudibranch sea slug, all of which are completely ridiculous.

Nudibranches are fairly small, typically only growing to about 20 centimeters (8 in), although there have been a few recorded nudibranches that were longer than 64 centimeters (25 in). They’re mollusks (like snails), but instead of using shells for protection, they have a few other tricks up their colorful sleeves—like sweating acid. If that’s not Alien enough, we don’t know what is.

5 Gorgonian Wrapper

The waters of the Indo-Pacific hold some of the most diverse marine life on the planet, including the gorgonian wrapper. The gorgonian wrapper is a sea anemone, so yes, that terrifying thing is a predator. And it’s as ruthless as it looks—anemones like the gorgonian wrapper produce something called a cnidocyte, which is essentially a small, toxic shrapnel grenade. Cnidocyte cells line the tentacles of anemones, and when a fish brushes against one (or millions) of them, a trigger activates and the cell explodes, sending paralyzing harpoons into the fish.

The biological process that fires the anemone’s venom is one of the fastest reactions in the animal kingdom. It takes less than 700 nanoseconds for the cnidocyte cell to shoot its deadly load (a nanosecond is one billionth of a second).

4 Wonderpus

With one of the best Latin names in the animal kingdom, Wunderpus photogenicus is a rare predatory octopus found off the coast of the Philippines. The name comes from the fact that people like taking pictures of them; they’re photogenic. But kittens are photogenic, and the wonderpus is anything but cuddly. They’re crepuscular hunters (they hunt at dawn and twilight) that stalk prey by creeping along the seabed on long, flattened tentacles. In stealth mode, their bright coloring fades until they blend in with the sand and coral. But try to attack one, and suddenly it becomes a violent blaze of red and orange, warning predators to stay away.

And like most octopuses, wonderpuses are remarkably intelligent. This video shows a wonderpus building a wall of coral to hide behind. We’re learning more about the wonderpus every day (they were only discovered in 2006), but they’ve certainly made it easier on us—the patterns of white spots on their backs are completely unique to each individual, like a fingerprint.

3 Lionfish

There are 10 species of lionfish, and it goes without saying that they’re one of the most recognizable types of fish in the world. Savagely beautiful and incredibly dangerous, all 10 species are native to the Indian Ocean and southern Pacific, although two species were introduced to the East Coast of North America in the ’90s. This is turning out to be a problem because they breed like underwater rabbits and have no natural predators.

In fact, the population explosion has gotten so bad that researchers in Honduras are actually trying to train sharks to eat lionfish. Normally, sharks won’t even go near the things. Right now, the only real danger to these predators is, ironically, themselves: In the absence of food, lionfish will eat each other.

2 Giant Siphonophore

Visually, this thing doesn’t look like much, but you need a sense of scale to really appreciate the giant siphonophore; they live in the deep sea and can reach lengths of more than 40 meters (130 ft). That’s the height of a 13-story building and longer than a blue whale, the world’s largest vertebrate.

But the giant siphonophore isn’t really a single animal, per se; it’s actually a colony of millions of creatures called zooids. Each cluster of zooids has a specialized purpose: Some are responsible for eating, others digest the food, and others have the task of defending the colony. When they all work together, the colony functions like a single organism. It’s like a country or (perhaps more accurately) a stack of midgets in an overcoat.

And because siphonophores live so deep (about a kilometer down, or half a mile), they’re constantly under a ridiculous amount of pressure—half a ton for every square centimeter of surface area. As a result, they’re difficult to study. When brought too close to the surface, they pop like a balloon because of the reduced pressure.

1 Bobbit Worm

There’s nothing about the bobbit worm that isn’t grotesque or morbid. Even its name came from a court case in 1993, involving a woman named Lorena Bobbitt, a knife, and . . . something else that looks like a worm. Equal parts Tremors Graboid and unholy hellspawn, the bobbit worm can grow up to three meters long (10 ft). It burrows into the sea bed, leaving a small portion of itself above the surface. When a fish wanders by, the worm lunges out, snags the fish with its massive pincers, and drags it underground.

Most specimens haven’t been found in the ocean—but accidentally stowed away in saltwater aquariums. They hitchhike into the aquarium in rocks and gravel taken from the ocean, then slowly grow under the radar. In 2009, a giant bobbit worm was found in Blue Reef Aquarium in England. It was noticed when the aquarium workers took apart the tank to figure out why all their fish were disappearing.