Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

10 More Obscure Hoaxes From History

We’ve talked before about how hoaxes have been a part of history for thousands of years. And while this might not be great news for the gullible people taken in by them, it does mean there are plenty of amazing stories just waiting to be told.

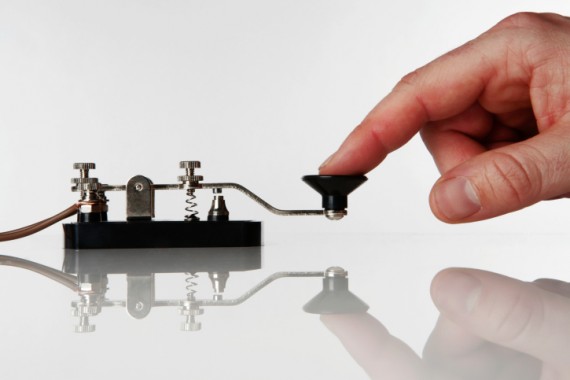

10The Snail Telegraph

In 1850, a Parisian inventor named Jacques Toussaint Benoit claimed to have invented a system of communication which could instantly transfer information across the globe, rendering the telegraph obsolete. It was called the pasilalinic-sympathetic compass and was based on Benoit’s belief that two snails which touched formed a telepathic link, hence its other name: the snail telegraph.

Benoit was broke and convinced a Parisian gymnasium manager named Monsieur Triat to invest in the project, receiving lodging and an allowance to continue his work. After Triat became annoyed at the lack of progress, Benoit finally agreed to demonstrate his contraption. On October 2, 1851, the machine was revealed for the first time to an audience of Triat and a French journalist. To Triat’s horror, the whole thing was obviously a hoax, since Benoit kept walking between the snails and prodding them. However, the journalist was completely fooled and wrote a raving article about the compass. When Triat demanded another test, with stricter rules, Benoit fled, dying two years later in a Parisian slum.

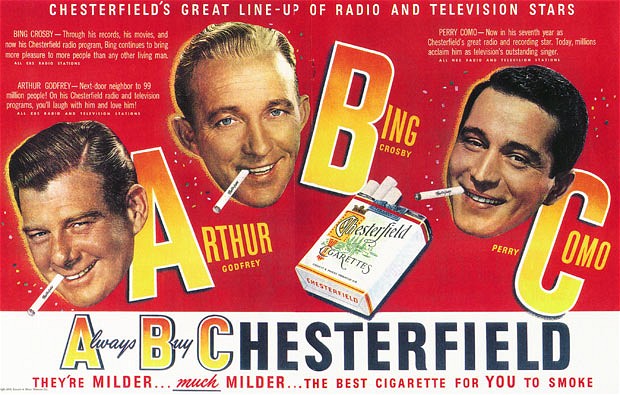

9The Chesterfield Leper

In 1934, the Chesterfield cigarette factory of Richmond, Virginia was hit by an extremely harmful rumor. Someone claimed that a leper had been found working in the production area and people fled the brand in droves. Liggett and Myers, the owners of the plant, denied the rumor, even going so far as to offer a $25,000 reward for evidence leading to the identification of the perpetrators of the hoax. Another rumor began, with people claiming the leprosy story was invented by a competitor, or a religious group which was opposed to smoking (that one was most likely a hoax as well). The source of the rumor was never revealed and the effects of the story were felt for over a decade, with sales extremely slow to recover.

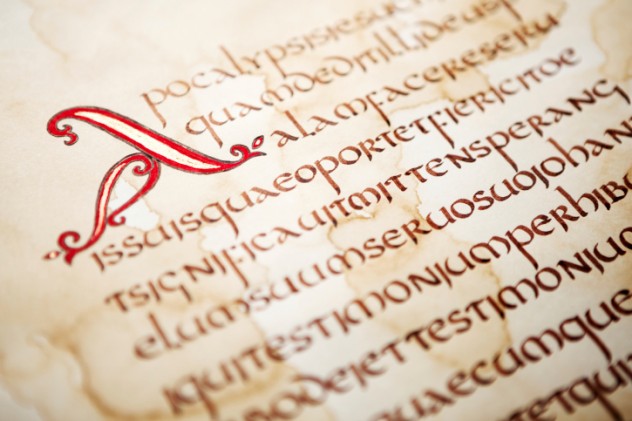

8The History Of Crowland Abbey

Crowland Abbey is located in the eastern part of England and has existed since the ninth century. In 1413, as the nobles of England were striving to seize the land from any monastery they could, a court case erupted over the abbey’s riches. Fortunately for the monks, they were able to present ancient documents, known as the Historia Crowlandensis, stating the clear ownership of the land by the inhabitants of Crowland Abbey. Cited by historians and scholars, the papers were believed to be real up until the 19th century, when people finally noticed some of the words weren’t used much in the ninth century, when the documents were said to originate. Even more damning were the references to universities that hadn’t actually been built yet. Perhaps as karma for their deceit, the monastery was dissolved in the 16th century and mostly demolished.

7The Boy With The Golden Tooth

In 1593, miraculous rumors began to spread throughout Silesia, an area of Europe mostly located in Poland, about a seven-year-old boy named Christoph Müller. The miracle, which was said to have taken place just before Easter, was that a golden tooth had appeared in the boy’s mouth. Jacob Horst, a professor at a nearby university, proclaimed the gold to be real and believed it was evidence of a supernatural force or an omen. However, in 1596, after extensive examination, it was determined that the tooth was not made of solid gold, but was actually a cap on the boy’s real tooth (this was impressive in its own right, as it was the first recorded example of a gold crown). In a bizarre twist, the only person known to have gone to jail because of the hoax was the boy himself.

6The Drummer Of Tedworth

In March of 1661 (or 1662, depending on the source), an excise officer named John Mompessen claimed to have heard supernatural drumming in his house in the town of Tedworth, in southern England. The noises began after he arrested a drummer named William Drury, who had tried to use forged papers in order to con the local constable out of money. Mompessen claimed Drury sent demons to his house as revenge and the drumming continued for months. Priests were brought in to perform exorcisms, but the noise persisted. However, when Charles II, the King of England at the time, sent representatives to examine the house, they couldn’t find any evidence of supernatural happenings. Although no one was ever found to be the originator of the noises, it is widely believed to have been a hoax (obviously, since ghosts and demons aren’t real).

5The Charlton Brimstone Butterfly

Here’s yet more evidence that even the brightest of us can be tricked if we don’t do our due diligence. In 1702, an avid butterfly collector named William Charlton sent a specimen to an esteemed London entomologist named James Petiver. Charlton died soon after, but his specimen was already causing a stir. It greatly resembled a common English Brimstone butterfly, except for black and blue spots on its lower wings, and Petiver believed it to be a new species. He eventually gave it to Carl Linnaeus, the great Swedish botanist and zoologist, who is considered the father of modern taxonomy. Linnaeus thought it was a new species as well, and included it in his Centuria Insectorum, a collection of 102 new species. It took 30 years for anyone to realize the spots were just painted on. The Danish entomologist John Christian Fabricius finally uncovered the hoax.

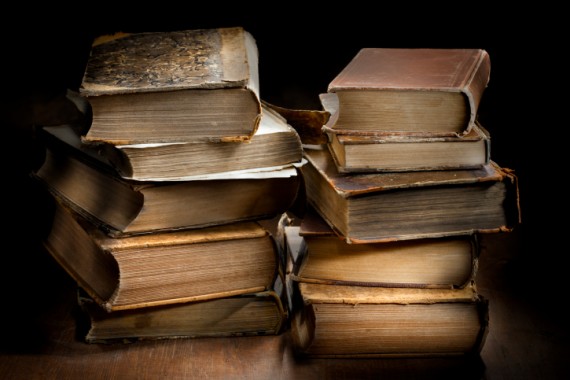

4The Fortsas Book Hoax

During the summer of 1840, a large number of rare book sellers and collectors were sent a telegram, claiming that one of the largest auctions of one-of-a-kind books in history was going to take place. A man named Count Fortsas was said to have recently died, leaving an immense library, and his children didn’t want to maintain his collection. The auction was set for August 10, 1840, in the small town of Binche, Belgium. People traveled from all over Europe to participate in the sale and flooded the city, unable to locate the place where the auction was to be held. Disheartened, they received notice the collection had been gifted to the Binche public library. However, there was no library in the city and it turned out the auction was all an elaborate hoax, perpetrated by a retired military officer named Renier Hubert Ghislain Chalon, who had a penchant for playing tricks on intellectuals.

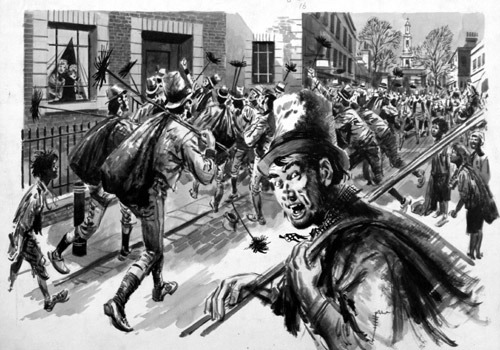

3The Berners Street Hoax

In 1809, a man named Theodore Hook, infamous for his weird pranks, bet his friend a guinea that he could make a small house on Berners Street “the most famous in all of London.” Hook rented a small room overlooking the house and set about with his plan. He contacted nearly every tradesman or business in the city, sending out thousands of letters, requesting their services on the morning of August 27. The first man to arrive was a chimney sweep, who was turned away—-only for another to arrive immediately afterwards (over 12 sweeps turned up in total). Over the course of the day, a huge number of tradesmen arrived, including piano movers, opticians, and barbers. The Mayor of London also turned up, for the owner of the house, Mrs. Tottenham, was well-respected. The crowd surged throughout the day, resulting in a number of fights, until they dispersed after dusk (police were dispatched to the ends of the street to keep anyone else from entering). Hook was eventually revealed to be the instigator, although his role wasn’t discovered until the anger about the hoax had died down.

2The Diaphote Hoax

In 1880, a man named Dr. H.E. Licks was said to have developed a new technology which allowed video to be transmitted over telegraph wires. The story was first published in a Boston newspaper and was reprinted over and over, even making it to the esteemed journal Nature. Derived from the Greek words for “through” and “light,” the diaphote was a series of mirrors, with wire interspersed throughout, which was said to use vibrations to determine shape and color. The invention was said to have been operated successfully in front of a number of witnesses, with images being sent in between two separate rooms. However, the entire story was a hoax, believed to have been the brainchild of an American civil engineer named Mansfield Merriman. It wasn’t revealed until 1917, in a book published under the name “H.E. Licks.”

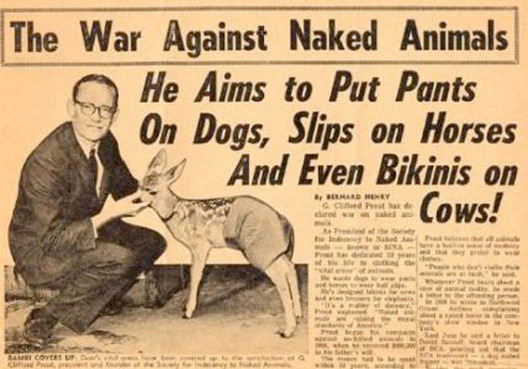

1The Society For Indecency To Naked Animals

In 1959, a new group was started with one goal in mind: to put clothes on animals, since they thought it was disgusting to see them walking around naked. (Their slogan: “A nude horse is a rude horse.”) Calling themselves The Society for Indecency to Naked Animals (pronounced “sinna”), the whole thing was actually a hoax, perpetrated by legendary prankster Alan Abel. His inspiration was an incident where a bull and a cow were having sex on a highway, upsetting a number of people. Using a series of press releases, Abel was able to convince people that it was a real organization and the “president,” played by an actor named Buck Henry, was even interviewed on Walter Cronkite’s CBS news show in 1962. The hoax began to unravel when someone on Cronkite’s staff recognized the actor. Abel prolonged the story until 1963, when Time published an article revealing the trick.