Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Hilarious (and Totally Wrong) Misconceptions About Childbirth

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Hilarious (and Totally Wrong) Misconceptions About Childbirth

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

10 Forgotten Modern Assassinations

The untimely death of a political figure has the potential to reverberate around the world. The assassinations of the Kennedy brothers, Benazir Bhutto, and Martin Luther King, Jr. are common knowledge, but not every political killing is so well-remembered. The murders on this list—while well-known in their own countries—have largely fallen out of popular consciousness internationally, yet each was an unfathomable tragedy. Some of the victims were inspirational campaigners against repressive governments, while others were simply good people doing their best in difficult circumstances. None deserved the fate that awaited them.

10 Munir Said Thalib

On September 7, 2004, a Garuda Airlines Airbus A330 took off from Jakarta, Indonesia, destined for Amsterdam. As the plane entered the final stage of its journey, nervous flight attendants informed the pilots that a passenger had been taken ill. Emergency services were waiting on the runway, but the man was dead by the time the wheels touched the ground. An autopsy found almost three times the lethal dose of arsenic in his body. His name was Munir Said Thalib and he was 38 years old.

Munir, as he was simply known, was born in the ancient Javan city of Malang. After studying law at Malang’s Brawaijaya University, he made a name for himself as one of Indonesia’s foremost human rights advocates. In the ’90s, Munir led a campaign that linked the Indonesian military to the disappearance of pro-democracy activists. He was also a prominent critic of military corruption and human rights abuses in East Timor. In return, his office was attacked and his family was threatened. When he was poisoned, Munir was on his way to study for a PhD that he hoped would give him a greater understanding of how nations could transition from a dictatorship to a democracy.

Suspicion fell on an off-duty Garuda pilot named Pollycarpus Priyanto, who was alleged to have been in contact with agents of Indonesia’s State Intelligence Agency. Priyanto had arranged to be on the same flight as Munir, brought him a drink, and apparently offered to switch seats with him, even though he had a business class ticket and Munir was in economy. A court found Priyanto guilty of the poisoning, but he was later acquitted on appeal after key witnesses withdrew testimony. The deputy commander of the State Intelligence Agency was also acquitted after the records of 41 calls he had made to Priyanto before the murder were found inadmissible as evidence, since he claimed the phone in question had been stolen. The transcripts of the calls were successfully deciphered but then mysteriously went missing. In 2010, Wikileaks cables revealed that US embassy officials believed there was evidence linking high-profile Indonesian security officials to the assassination.

9 Lounès Matoub

Music has a power to move people that makes it a powerful political tool—and potentially a dangerous one. Lounès Matoub spent his life using music to speak for the marginalized and oppressed. One of Algeria’s most popular musicians, Matoub was a member of the Berber Kabyle ethnic group. He was politicized at a young age, when Algeria’s Arab-nationalist government tried to force Berber children to learn only Arabic in schools. The already fiercely patriotic Matoub responded by skipping the classes altogether, and would boast later in life that he could not speak a word of Arabic.

A virtuoso who built his first guitar at age nine, Matoub played his first concerts in 1980, during a period of protest known as the Berber Spring. Known as the “Lion of Kabylia” for his direct and uncompromising lyrics satirizing Algerian politics, Matoub championed Berber identity and cultural rights and argued for democracy and religious tolerance.

As Algeria headed towards civil war between the government and Islamist rebels, Matoub made enemies of both sides. In a famous interview on French television, he stated that he was not an Arab and was not obliged to be a Muslim. In 1988, he was shot in the stomach by a policeman and spent two years recovering, during which time the government tried to destroy his reputation by claiming he was a homosexual drunkard and a spy for the secret police. In 1994, he was kidnapped by Islamist rebels and sentenced to death as an “enemy of God.” He was released two weeks later, as outraged members of the Berber community threatened to go to war against the rebels if he were not released.

Three years later, Matoub was driving back from lunch with his family when unseen assailants riddled his car with 78 bullets. Miraculously, his wife and her two sisters survived, but the Lion of Kabylia was not as lucky. More than 50,000 people attended his funeral, while the Kabyle region was rocked by days of violent riots. It has never been exactly clear who was responsible for his death, with the government and rebels both considered prime suspects. At the funeral, Matoub’s family played one of his last recordings—a scathing parody of the Algerian national anthem. A few days later, the government passed a long-mooted law making Arabic the country’s only official language.

8 Zoran Djindjic

In October 2000, furious street protests raged across Belgrade. The protesters demanded the removal of Serbia’s notorious president, Slobodan Milosevic. At their head was a charismatic former philosophy teacher named Zoran Djindjic. In 1996, Djindjic had been elected the first non-communist mayor of Belgrade. When Milosevic attempted to ignore the result of the election, Dindic organized daily protest rallies for three months until he was instated. In 2000, the protesters won again—Milosevic was forced out and Djindjic became Prime Minister of Serbia’s first post-communist government.

As Prime Minister, Djindjic was a relentless reformer, fighting to modernize the economy and entrench democracy. His policies were widely acclaimed in the West, although he also attracted some criticism for his willingness to resort to backroom deals to achieve his reforms. In 2001, he was crucial in arranging for Milosevic to be extradited to face trial for war crimes in The Hague. Then, in 2003, he arrived at a Serbian government office for a routine meeting with Swedish Foreign Minister Anna Lindh. As he exited his car, a sniper’s bullet penetrated his heart. He died instantly.

Death by sniper is actually a relatively rare form of assassination, and suspicion immediately fell on the small number of people with the military experience to carry it out. In 2007, Milorad Ulemek, the former head of Serbia’s elite Red Berets paramilitary unit, was convicted of ordering the murder. A career criminal who had spent six years hiding out in the French Foreign Legion, Ulemek rose to prominence during the Yugoslav Wars of the ’90s, first as an associate of the warlord Arkan and then with the Red Berets. His unit was known to have carried out killings on behalf of Milosevic. After the war, Ulemek became a senior figure in the Zemun Clan crime syndicate. Djindjic had spearheaded a crackdown on organized crime, and whether his death was the result of politics, crime, or some combination of both remains unclear. The man who pulled the trigger, Zvezdan Jovanovic, told the police he felt no remorse at all for the crime.

7 Anna Lindh

The woman who was to meet Djindjic on that fateful day would meet an equally tragic fate. A veteran politician noted for her work on European environmental regulations, Lindh was appointed Foreign Minister in 1998 and was widely tipped to become the first female Prime Minister of Sweden. Then, on 10 September, 2003, Lindh went to a Stockholm department store to buy an outfit for a TV debate scheduled that night. As she browsed, Lindh was approached by a Swedish man of Serbian parentage named Mijailo Mijailovi. He stabbed her repeatedly in the arms, chest, and abdomen before dropping the knife and fleeing the scene. Lindh clung to life for hours, before dying in the hospital in the early hours of September 11.

Lindh was not accompanied by any bodyguards, a fact which drew comparisons to the unsolved 1986 assassination of Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme and prompted the Swedish government to revise its security policies. Her murderer initially escaped the scene, but was arrested a few days later. He had a history of mental problems, asked for Tom Cruise as his lawyer, and could give no reason for the murder other than the claim that voices in his head had told him to attack. He later changed his story, claiming that his original confession was an attempt to be declared too mentally unstable to face prison and that he had actually killed Lindh out of a generalized hatred for all politicians. Lindh’s death came almost six months to the day after Djindjic’s.

6 Eric Ohena Lembembe

The West African nation of Cameroon is not a good place to be gay, much less a gay rights activist. Under the country’s current laws, homosexuality is punishable by up to five years in prison, and anti-gay sentiments are commonplace. In 2012, a man was sentenced to 36 months in prison for simply sending a text message telling another man he loved him.

Nonetheless, Eric Ohena Lembembe was prepared to stand up for what he believed in. Cameroon’s most prominent gay rights campaigner, Lembembe was also a journalist and the head of the AIDS charity Camfaids. In 2013, he published a blog post documenting attacks on gay and lesbian groups and warning that the government was often unwilling to prosecute the perpetrators. Less than a week later, he was dead.

His body was discovered by friends, who had grown alarmed after being unable to contact him. Peering through the window of his house, they were horrified to see Lembembe’s corpse lying on the bed. His feet had been broken and his hands and face had been burned repeatedly with an iron before the attackers broke his neck. Homosexuality remains illegal in 38 African countries and Cameroon’s neighbor Nigeria recently passed harsh new anti-gay legislation.

5 Galina Starovoytoya

The fall of the Soviet Union triggered an extraordinary explosion of corruption and greed. The USSR’s creaking state infrastructure was sold off at a fraction of its true value, as billionaire oligarchs became the most powerful men in the country. As violence erupted in the Caucasus, it was rare to find a high-profile politician with a reputation for probity and honestly. Galina Starovoytoya was one of the exceptions.

An academic from the remote Ural Mountains city of Chelyabinsk, Starovoytoya was thrust into politics in 1988 when a letter she wrote to two Armenian friends created a huge stir in the country. The letter, which argued in favor of self-determination for the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region, earned her a reputation as “the first Russian to attempt to understand the Armenian position.” A year later, she was elected to the Soviet Congress from Armenia, an unheard of feat for a Russian.

In the Congress, and later in the Russian Parliament, Starovoytoya developed a reputation as one of the country’s foremost human rights campaigners. She frequently spoke out against corruption, antisemitism, and Russia’s slide back towards authoritarianism. In the buildup to the First Chechen War, she attempted to reach out to Chechen leader Dzhokhar Dudaev, who responded positively to her offer of talks. Hawks in the Kremlin, convinced the war would be short and easily won, declined to negotiate. When Starovoytoya tried to get through to Dudaev again, she found the phone lines between the Russian Parliament and Grozny had been cut. In 1998, the year she was killed, Starovoytoya began investigating alleged links between organized crime and Russia’s security services and senior politicians.

On November 20, Starovoytoya was climbing the staircase of her apartment building when she was ambushed by two assassins, who raked her with submachine gun fire. The murder was found to have been orchestrated by a a hitman named Yuri Kolchin, a former agent of Russia’s military intelligence. Starovoytoya’s body lay in state in St. Petersburg’s Museum of Ethnography as over 20,000 people braved the freezing winter temperatures to pay their respects. At the time of her death, she had been planning to run for governor of the region. Reflecting on his mother’s willingness to stand up to corruption and extremism, Starovoytoya’s son called her death “utterly predictable.” It was never determined who ordered the hit on her.

4 Satyadeow Sawh

Satyadeow Sawh was not, by most standards, a great mover-and-shaker in the world of politics. Born in Guyana, he migrated to Canada at age 18, received a degree in economics, got married, and raised a family. He was active in the Guyanese community in Canada and eventually returned home to take up posts as an ambassador and Fisheries Minister. In 2003, he was appointed Minister of Agriculture. Three years later, a group of heavily armed men in military fatigues entered his home, killing a security guard on the way. Sawh’s wife had time to shout a warning, but he was shot dead as he rose to flee. The gunmen fired several shots into his body before moving on to the other residents of the house. Sawh’s brother and sister were killed. His wife and another brother were injured but miraculously survived.

What was initially assumed to be a robbery gone wrong soon took on an even more sinister tone. The Guyanese police attributed the murders to Rondell Rawlins, a former soldier turned gang-leader and river-pirate who was believed to be responsible for massacres of policemen and civilians in the towns of Bartica and Lusignan. Rawlins, Guyana’s most wanted man, was said to blame the government for the supposed disappearance of his pregnant girlfriend. However, this account has been disputed by many, including Sawh’s brother and Guyana’s main opposition party, who have questioned the speed with which the police investigation was closed. In 2008, a man claiming to be Rondell Rawlins called a local newspaper to take responsibility for the massacre in Lusignan, but denied involvement in Sawh’s death. Some have even claimed that there were two groups working independently of each other in the house that night. Rondell Rawlins was shot dead in a confrontation with police in 2008. The murders will probably never be solved to everyone’s satisfaction.

3 Paul Klebnikov

Paul Klebnikov was an investigative journalist to his bones. Born in New York to Russian parents, he joined Forbes Magazine in 1989 and made a name for himself investigating the corruption that plagued Russian businesses in the ’90s. He frequently received death threats and briefly fled Russia after publishing pieces on the powerful oligarch Boris Berezovsky and his close relationship with Boris Yeltsin. He soon returned, and in 2003, he was appointed editor of Forbes’s new Russian edition. Less than a year later, he was walking home late at night when a passing car slowed down and a passenger fired four shots into his body. He briefly clung to life, but died at the hospital after the elevator taking him to surgery broke down.

No one was ever convicted of the crime. The Russian authorities declined US assistance in investigating the case. In 2003, Klebnikov had published a book of interviews with the Chechen rebel leader Khozh-Akhmed Nukhayev, who Russian officials treated as the main suspect in the killing. Others have suggested the murder was linked to his investigations of Berezovsky or even to an article Forbes had published on Russia’s 100 wealthiest people, which had apparently ruffled many feathers. Klebnikov’s death was part of a spate of attacks on Russian journalists that included the notorious murder of Anna Politkovskaya.

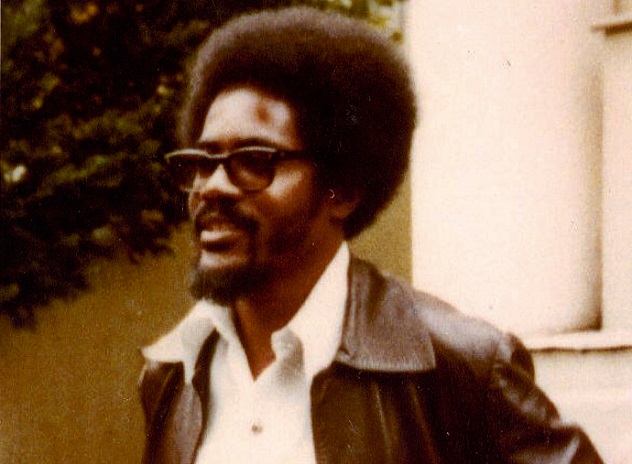

2 Walter Rodney

When Walter Rodney stepped off a plane in 1974 and back onto his native Guyanese soil, a sense of anticipation hung in the air. One of Guyana’s most brilliant sons, Rodney was an internationally recognized historian who had become better known as an activist and a leading figure in the Pan-African movement. A formidable scholar, Rodney had won a full scholarship to London’s renowned School of African and Oriental Studies, where he impressed by learned Spanish and Portuguese in order to be able to examine ancient colonial records from those countries. Taking a teaching post at the University of the West Indies in Jamaica, Rodney shook up the island’s status quo by associating with the islands then-marginalized Rastafarian community and the impoverished working class. When he left to attend an academic conference in Canada, the Jamaican government banned him from reentering the country, a decision that caused days of rioting.

After six years of teaching in Tanzania, Rodney was invited to take up a post at the University of Guyana. No sooner had he stepped off the plane, however, than word arrived that the job offer had been rescinded thanks to government pressure. Undaunted, Rodney stayed anyway and soon joined the opposition to Guyana’s authoritarian and unstable leader, Forbes Burnham. His focus on reaching out to the youth and developing a multi-racial democracy, which would cut through the often-strained relationship between the Afro-Guyanese and the slight Indo-Guyanese majority, proved popular and he soon became the leading opposition figure. Then, in 1980, his life came to an abrupt end when a bomb exploded in his car.

According to Rodney’s brother, who was injured in the explosion, the bomb was concealed in a radio given to him by a sergeant in the Guyana Defense Force named Gregory Smith. The official government story was that Rodney had been killed by a bomb he himself had made in order to stage a prison break. Gregory Smith was spirited out of the country on board a plane bearing a Guyanese Defense Force insignia. He was later found living under an assumed name in French Guiana, but the Guyanese government declined to press for his extradition. Meanwhile, his wife was given a lucrative government job in Guyana. Burnham’s increasingly autocratic rule continued until his death five years later.

1 Ruth First

On August 17, 1982, a parcel was delivered to the Eduardo Mondlane University in Maputo, Mozambique. It was addressed to Ruth First, the formidable Director of the University’s Centre for African Studies. When she opened it, the bomb inside exploded, ripping through the office. First died instantly. Over a decade later, South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission determined that the bombing had been ordered by Craig Williamson, a police major and spy for South Africa’s apartheid government.

To understand the reasons for this tragedy, we have to go back 40 years to South Africa’s University of the Witwatersrand and a remarkable young woman determined to stand up to injustice and inequality. Ruth First probably doesn’t fit the image most people have of a rebel against apartheid. The daughter of Eastern European immigrants, she could have comfortably lived her whole life as a member of the relatively privileged white social group, but First had been heavily influenced by her left-wing parents’ opposition to the South African government. At Witwatersrand, her fellow students would include Nelson Mandela, Mozambican revolutionary Eduardo Mondlane, and a young man named Joe Slovo.

Like First, Slovo was the child of Eastern European immigrants, a communist, and a tireless opponent of apartheid. The two were married in 1949 and became active in the South African Communist Party, a firm ally of the African National Congress in the fight against apartheid. First became a reporter and was well known for her articles unflinchingly documenting the harsh treatment of the country’s black population. In 1960, she fled the country, but soon returned. In 1963, she was arrested and kept in solitary confinement without trial for the maximum allowed period of three months. As soon as she stepped out of the prison, she was re-arrested and held for another month. During this time, First attempted suicide and her elderly father was forced to flee the country.

After being released, First went into exile, first in London and then in Mozambique. Through her writing, she remained one of the leading figures in the anti-apartheid movement. Then, on that fateful day in 1982, bomb-maker Joe Raven slipped a powerful explosive device into the parcel destined for First on the orders of Craig Williamson. As part of the movement towards reconciliation after the fall of apartheid, both men were granted amnesty for their crimes. Neither will ever face any jail time.

Alex has also written for Cracked.com. If you enjoy being vaguely underwhelmed, you can follow him on his shiny new Twitter account.