Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Momentous Events That Also Occurred on July 4th

Animals

Animals 10 Times Desperate Animals Asked People for Help… and Got It

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Flops That Found Their Way to Cult Classic Status

History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Music Biopics That Actually Got It Right

History

History 10 Momentous Events That Also Occurred on July 4th

Animals

Animals 10 Times Desperate Animals Asked People for Help… and Got It

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Flops That Found Their Way to Cult Classic Status

History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

10 Cool And Quirky Things We Learned About Animals In 2013

Like any year, 2013 had its ups and downs, its surprises and disappointments, but overall, it was a great year for zoology. Researchers discovered new creatures like the olinguito, found out that crickets have a tendency to show off, and learned that bees can sense the electrical fields created by flowers. And while a new year has rolled around, we’re still fascinated by the cool and quirky things we learned about animals in 2013.

10 Grasshopper Mice Are Immune To Scorpion Venom

There are mice, and then there are grasshopper mice. While your average mouse gnaws seeds and is a bit of a coward, grasshopper mice are insane serial killers. Unlike most mice, these guys eat meat. They hunt lizards, insects, arachnids, and even other mice, and before delivering the coup de gras, they rear up on their hind legs and let loose with a terrifying, high-pitched howl. And in 2013, researchers discovered yet another reason little creatures should fear the grasshopper mouse. They’re immune to bark scorpion venom.

Bark scorpion stings are painful, like being “burned with a cigarette and then driving a nail in” painful. These eight-legged beasts can even kill small children, so Ashlee Rowe of the University of Michigan wondered how grasshopper mice ate them on a regular basis. Intrigued, she injected bark scorpion venom into the back paws of wild mice, and to compare and contrast, she followed the procedure with a group of common house mice. After the injections, the house mice licked their wounds for about four minutes while the tough-as-nails grasshopper mice licked their wounds for a few seconds before scampering off to murder tiny animals.

Next, researchers injected the mice with a formalin solution. While this would’ve caused intense pain for your average mouse, these little dudes just shrugged it off. Are grasshopper mice immune to everything? Yes, if they’ve recently been stung by a bark scorpion that is. Usually, when a venomous creature stings a mouse, the toxins activate sodium channels in the mouse’s nerve cells. This allows sodium to flow into its cells, sending a pain signal to the brain. However, the grasshopper mouse is hardwired in such a way that a special channel shuts off the flow of sodium which actually turns the venom into a painkiller. That’s why the mice weren’t hurt by the caustic formalin injections.

The implications of this discovery could be pretty huge as pharmaceutical companies might finally figure out how to block sodium channels in the human body. Someday, we might all become Supermen, impervious to pain, thanks to these Mighty Mice.

9 Crocodiles And Alligators Use Tools

Perhaps the coolest thing we learned about animals in 2013 was documented by Vladimir Dinets of the University of Tennessee. We all know animals use tools to make their lives easier, but in 2013, researchers documented the first instance of reptiles using tools to catch their prey. That’s mind blowing.

In his study, Dinets describes how American alligators and mugger crocodiles use sticks to capture birds, a process so simple it’s terrifying. These crocodilians live in swampy areas which are also home to egrets and herons. Every year, the birds need to build nests for their eggs, and that’s when the reptiles strike. Imagine you’re a heron in a Louisiana bayou, and you need to make a nest ASAP. Competition for building supplies is fierce. You’re poking around, looking for sticks, when you see several floating in the water. They’re just the right size, but as you lean down to pick them up, something shoots out of the water and snap! There was an alligator under the water the whole time, and the sticks were resting on his snout, a trap to lure in lunch.

What’s truly amazing is the crocodilians only set their traps during nesting season. Not only have they discovered how to use sticks as camouflage, they’ve figured out when the birds need them the most. It look like these reptiles are far more cunning and creative than we previously thought, which is bad news for birds and one-handed pirates everywhere.

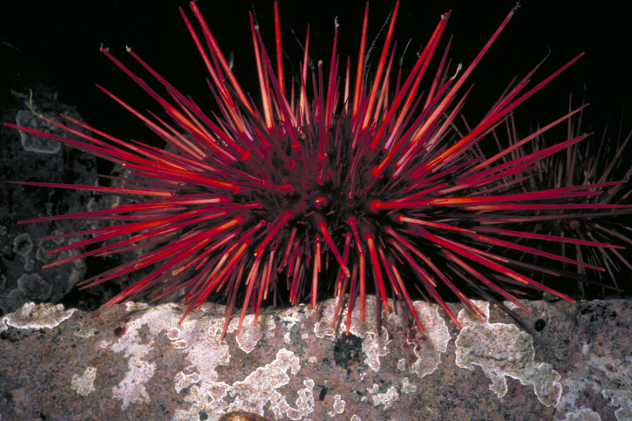

8 Sea Urchins Might Save The World

When most people picture sea urchins, they think of spiky little balls that don’t really do anything. Only most don’t realize urchins might hold the fate of the world in their, uh, spines. As it turns out, scientists recently discovered these sea hedgehogs might offer a solution to one of the world’s biggest problems—global warming.

Strange as it might seem, urchins are born as squiggly little larvae, and during their larval stage, the urchins convert CO2 into calcium carbonate which is the same stuff we use to make cement and plaster casts. The urchins use this chemical compound to build their barbed shells, but scientists weren’t exactly sure how the creatures were sucking up all that carbon dioxide, until Lidija Siller of Newcastle University decided to run a few experiments.

In her lab, Siller discovered the sea urchin’s exoskeleton contains a large amount of nickel, enough to absorb all the surrounding CO2 and turn it into harmless calcium carbonate. And not only does nickel give the sea urchin its trademark punk look, it might also save the planet. As the climate steadily changes, most researchers are considering pumping CO2 into underground reservoirs, but the process is expensive and pretty difficult. Instead, Siller believes if industrial plants used a nickel catalyst, they could trap carbon dioxide before it escapes into the atmosphere, and then they’d be able to use the resulting calcium carbonate in products like glass and pharmaceuticals. They’d basically be giant industrialized sea urchins, just without all the cool spikes.

7 Veiled Chameleons Trash Talk With Color

Trash talk is an essential part of combat sports. Fighters like Mike Tyson and Muhammad Ali tear their opponents to pieces even before they step into the ring, and in that respect, they aren’t too different from male veiled chameleons. According to a study by Russel Ligon and Kevin McGraw of ASU, veiled chameleons signal to each other with their body stripes before a match-up, and their colors usually indicate who’s going to go home with the belt.

While scientists knew chameleons signaled to each other before fights, they weren’t sure what those color changes indicated in the world of chameleon karate—until Ligon and McGraw set up contests between these Middle Eastern reptiles. Ten lizards squared off in a series of 45 fights while researchers took notes and recorded the scaly showdowns with digital cameras, paying particular attention to 28 color spots along the chameleons’ bodies. Afterwards, they went back and analyzed the footage, breaking down the fights and deciphering what the reptiles were saying.

A lot of the matches started the same way. Two lizards would confront each other and immediately begin flashing their stripes. These displays helped the chameleons look bigger and showed who really wanted to fight. Chameleons with bright stripes were basically saying, “Let’s go, chump!” Chameleons with duller stripes often decided to spend a few more hours in the gym before squaring off. However, there were times when, regardless of color, neither lizard retreated. Instead, they began biting and head-butting, and as they duked it out, researchers noticed the colors on their heads were flaring. It turns out whichever chameleon changed colors faster during the fight was almost always the winner of the bout.

So what is it about these stripes? How do they turn chameleons into ultimate fighters? Ligon and McGraw think these rapid color changes are probably linked to how much energy the lizards have. They’re basically signaling how strong and virile they are. The more eager they are to scrap, the brighter the stripes. And if their stripes are dull and drab, then they go home beaten and bruised, hopefully to find their eye of the tiger.

6 Birds Pay Attention To The Speed Limit

We’ve already read about how pigeons are abstract thinkers and how herons make their own fishing lures, but believe it or not, our fine feathered friends recently kicked it up a notch on the intelligence scale. In 2013, Canadian scientists Pierre Legagneux and Simon Ducatez revealed that birds are paying attention to speed limits. That’s especially impressive when you think about how many humans don’t.

While most of us listen to the radio on our drive to and from work, Legagneux and Ducatez were busy paying attention to birds on the side of the road. As they drove back and forth to their lab, they noticed the birds took off when their car was a certain distance away. What’s more, the birds’ reactions differed from road to road depending on the traffic signs. For example, let’s say they were cruising down a road with a 50 km/h speed limit (31 mph). As the car slowly made its way down the road, the birds would sit around and peck at roadkill until the car was about 15 meters away (50 ft). However, if researchers tore down a highway with a 110 km/h speed limit (68 mph), then the birds flew off when they were 75 meters away (246 feet). That’s a pretty significant difference.

However, there’s a twist. If the scientists drove 110 km/h down a 50 km/h road, the birds waited until the car was 15 meters away before taking off. They weren’t responding to the speed of the cars but to the traffic signs posted on the roads! Well, sort of. The birds were actually observing cars and determining the average speed of traffic for each individual highway. Not only did this keep them alive, but it gave them more time to safely look for food. Thanks to survival of the fittest, our planet will soon be full of road sign-reading, abstract-thinking, tool-using birds. It’s Alfred Hitchcock’s worst nightmare come true.

5 Elephants Understand Human Gestures

Pointing is a universal human gesture. It’s so basic that babies learn to do it by their first birthday. However, when we try to explain hand signals to our animal friends, it doesn’t go very well. Not even those brainy chimpanzees understand what our gestures mean. A few animals, like dogs, grasp the concept, but they have to be trained. However, if Ann Smet of the University of St. Andrews is right, there’s one creature that just gets it.

Elephants are like the long-trunked Einsteins of the animal kingdom. We’ve already read about how they’re self-aware, use tools, and have intricate death rituals, and Smet believes African elephants comprehend human gestures without any previous training. Smet’s team experimented on eleven captive elephants working at a lodge in Zimbabwe, choosing this group because their trainers use vocal cues instead of body language to communicate with the pachyderms.

Smet’s test was pretty simple. An elephant watched as she displayed a piece of fruit. Then she stepped behind a screen and hid the treat in one of two buckets. Next, she brought the buckets out, set them down and pointed at the one with the fruit. After numerous tests, Smet found the elephants picked the correct bucket 67.5 percent of the time. At first, that might not sound so impressive, not until you realize that one-year-old human babies scored an average of 72.7 percent on a similar test. Essentially, elephants are about as smart as your baby . . . or your baby is about as stupid as an elephant. It all depends on your perspective.

4 Termite Poop Is Powerful

Termites are pretty pricey pests, like US$40 billion a year in damages pricey (worldwide), and there’s not a lot exterminators can do, biologically speaking anyway. For the past 50 years, scientists have tried to massacre termite colonies with microscopic assassins, but so far they’ve been unsuccessful. It wasn’t until 2013 that scientists revealed why termites were immune to biological weapons, and it was a pretty crappy reason.

Scientists from the University of Florida focused their research on the ever-hungry, uber-destructive Formoson subterranean termite, C. formosanus. The researchers attacked a number of colonies, some in the lab and some outdoors, with Metarhizium anisopliae, a killer fungus. Normally, M. anisopliae wipes out any insect in its path, but it was useless against C. formosanus, and that was thanks to the termites’ poop.

Termites have the disgusting habit of using their droppings to build their nests (their health codes are very different from ours), and nothing loves termite feces more than actinobacteria. These guys chow down on termite dung, and in exchange for the free food, they provide C. formosanus with chemicals that kill fungi, making it virtually impossible to eliminate them with biological agents. This study is sad news for exterminators, but there might be a silver lining under all that manure. If actinobacteria can help termites, maybe it can provide us with antibiotics too. We might be curing our future ills with creatures that eat termite poop. Think about that the next time you’re at the pharmacy.

3 How Do Roosters Know When To Crow?

The most iconic of all barnyard animals, the rooster is known across the world for its ear-shattering “cock-a-doodle-doo.” They’ve been waking up farmers for centuries, but how do these feathered alarm clocks know it’s morning? Do they need to see the sun? Or do they just inherently know it’s time to get everyone out of bed? A team of Japanese researchers from Nagoya University decided it was time to find out. (Somebody has to investigate the little stuff, right?)

The researchers took four groups of roosters, placed them in separate rooms and subjected the birds to 12-hour alternating periods of bright and dim light. The roosters picked up on the pattern and began crowing two hours before the bright lights came on.

A second test involved keeping the rooms dark on a twenty-four hour basis. Every once in a while, a confused rooster would call out during the afternoon, but most crowed during the early morning hours. Despite the darkness, their circadian rhythms told them when the sun was rising . . . for about two weeks anyway. After that, their instincts started to fade, and the crowing grew more and more sporadic. The researchers concluded as long as they’re regularly exposed to the sun (and not locked up in dark rooms for weeks), roosters know when the sun is rising thanks to their biological clocks.

However, the experiments weren’t over yet. As any farmer can tell you, a rooster will crow if he spots a random light (i.e. headlights). Researchers wanted to find out how gullible these fowls were so they flashed bright lights and blasted the birds with recordings of other roosters. While these tricks caused a few birds to crow throughout the day, the tests ultimately proved the roosters were more likely to vocalize in the morning, proving their circadian rhythms were still playing an important role. But what’s the ultimate goal of a study like this? By cracking the rooster code, scientists hope they might open a door into the world of animal vocalization. If we can understand the intricacies of a cock-a-doodle-doo, then we might learn the meaning of a dog’s bark or a cat’s meow or even what the fox says.

2 Dolphins Use Names

You might call him Flipper, but other dolphins know him by a distinctive, high-pitched whistle. Just like others call you “Bob” and you “Jen” (there’s a Bob and Jen in the audience, right?), dolphins use actual names to distinguish themselves from members of their pod, according to a new study by a team from the University of St. Andrews. Scientists have known for some time that whistles play a vital role in dolphin language, but it wasn’t until 2013 that Dr. Vincent Janik revealed how complex a system it truly is.

Janik and his crew found a pod of bottlenose dolphins off eastern Scotland and recorded their whistles and clicks. Then Janik broadcasted their signature sounds into the water, and when he did, the dolphins started talking back. For example, let’s say there was a dolphin named “Marino.” Janik played Marino’s identifying whistle, and Marino would respond with a sound that meant, “Hi! Did you call me?” But if Janik played random sounds, like the name of a dolphin from a different pod, the mammals kept quiet, proving they weren’t squeaking just for squeaking’s sake. Janik’s discovery is pretty amazing considering that no other species of animal—with perhaps the exception of parrots—uses names. But then, dolphins are the second most intelligent species on the planet.

1 Mice Inherit Fear

Emory University scientist Kerry Ressler was working with the inner city poor when he noticed kids were inheriting substance abuse problems and mental disorders from their parents and then passing those same problems on to their kids. Curious if maybe the problem was biological, he returned to the lab, conducted experiments and came up with a very controversial conclusion. According to Ressler and his partner Brian Dias, children—specifically, mice children—inherit the fears of their parents.

First, Ressler sprayed a chemical called acetophenone into a cage full of mice. The chemical itself was harmless and even had a sweet fruity smell, kind of like cherries. Ressler coupled the scent with electric shocks to the mice’s feet so the rodents would associate acetophenone with pain. After the mice grew to dread the smell, he bred them and ran a series of tests on their offspring. However, he didn’t use any electricity this time. He simply sprayed their cage with acetophenone, and their reaction was quite surprising. Even though these new mice had never smelled acetophenone before, they were terrified of it. Whenever they got a whiff of that fruity scent, they started to shudder. What’s even more amazing is that these second generation mice passed the fear to their offspring, meaning the grandchildren of the original mice were still terrified of acetophenone even though they’d never been shocked.

When scientists examined the test animals, they found all three generations of acetophenone-fearing mice had more than the usual number of neurons meant to build receptor proteins. That’s a pretty big deal as these receptors are used to detect odors. Scientists also found the structures that process signals from those neurons were bigger than usual. But what was the cause behind these changes? Ressler and Dias point to epigenetics. Epigenetics is basically the study of how our environment, from our diet to the weather to our personal choices, affects our genetic inheritance. Many think Ressler and Dias are promoting ideas similar to the disproven theory of Lamarckian inheritance. However, if Ressler and Dias are right, their discovery might unlock the secrets to conditions like obesity, diabetes, PTSD and even autism.

Nolan Moore learned about Listverse in 2013 and plans to keep writing lists in 2014.

If you want to send him ideas for a list, shout at him a little bit or just drop him a line, you can contact him at [email protected].