History

History  History

History  Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

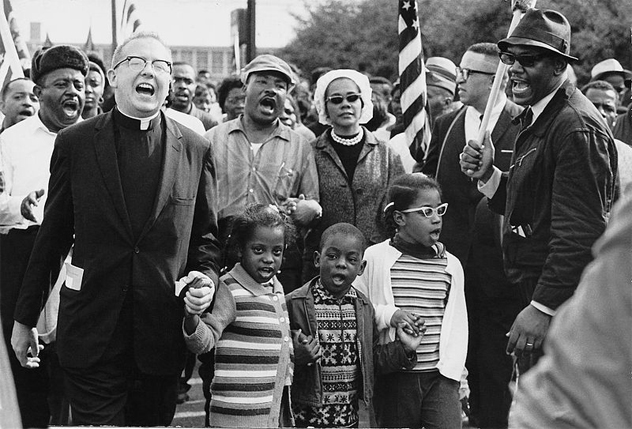

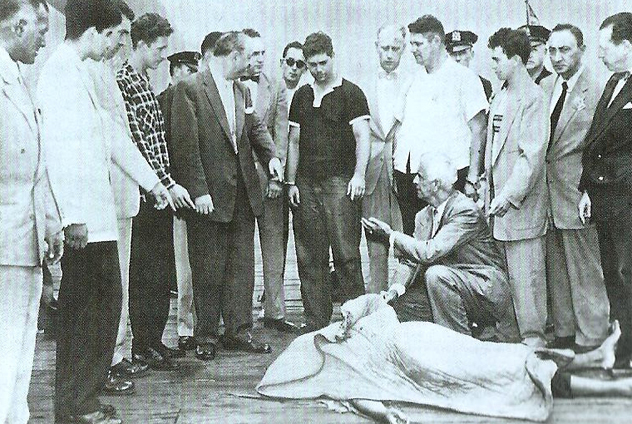

10 Forgotten Martyrs Of The American Civil Rights Movement

You know Martin, Malcolm, and Medgar, but there are so many others who gave their lives to a cause that changed the world. Their names and lives should be remembered, and their legacy honored.

10 Jimmie Lee Jackson

Known as the man whose death gave life to the Voting Rights Act, Jackson was an Army veteran. Like many other black Alabama residents, he was deeply troubled at being prevented from registering to vote. Numerous times he had tried to register, only to be blocked at every turn by some ridiculous rule. On February 18, 1965, a group of 400 people met in a local Marion church to pray, sing, and hear stories from a group of Selma residents who were attempting to register to vote.

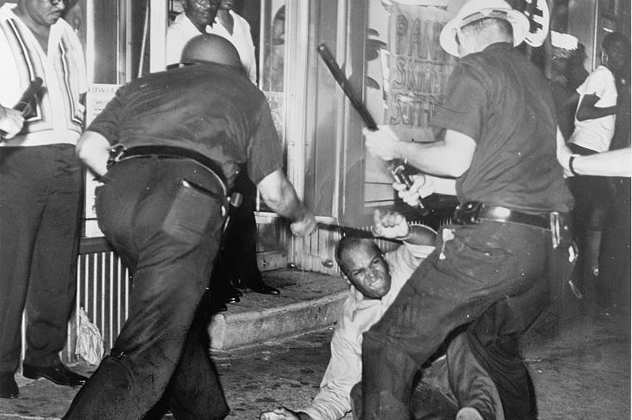

When the group left the church, planning to march to the jail to pray and sing, they were attacked by state troopers in riot gear. Photographers on the scene were prevented from recording the event, and any who pressed the matter were beaten and their cameras destroyed so that no photographic evidence survived the violent night. Lee was with his mother and elderly grandfather, and in the chaos, the trio sought shelter in a nearby business. A trooper threw Lee’s mother to the ground, and when Lee sought to shelter her, the trooper drew a gun and shot Lee twice in the abdomen at point-blank range. Lee died several days later.

Four days after that, the protesters rallied again for the famous march from Selma to Montgomery, a day which became known as Bloody Sunday—and this time, the press did capture the event. Outrage boiled across the nation, spurring President Johnson to finally sign the Voting Rights Act of 1965 into law the following August. As for the trooper who fired the fatal shot, he was tried in 2010 and given a mere six-month sentence for second-degree manslaughter. The court released him early.

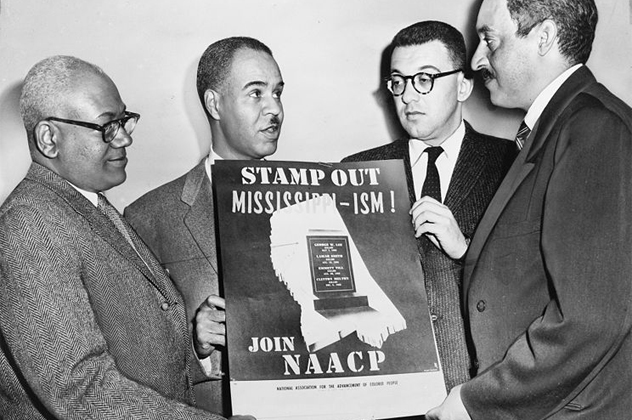

9 Clyde Kennard

A Korean war veteran, Kennard attended the University of Chicago from 1953 until 1955, when he was forced to return home to Hattiesburg, Mississippi, to help out his mother. Kennard wished to finish his education, but the only college in the area was the all-white Mississippi Southern College, now the University of Southern Mississippi. Kennard met with school officials on a number of occasions and formally applied to the school in 1955. School officials put up roadblock after roadblock to thwart his admission, and the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission, a state-funded secret agency dedicated to segregation, attempted to discredit Kennard.

Unfortunately for them, the devout Baptist man had an impeccable life and school record. They couldn’t dissuade him, so they framed him with a felony: stealing $25 worth of chicken feed. An all-white jury convicted him to the maximum of seven years of hard labor after a brief 10-minute deliberation. While incarcerated for a crime he did not commit (the key witness later recanted, and stated that the whole charade was to bar him from the college), he became seriously ill with what was discovered to be intestinal cancer. Prison officials refused to treat him, release him, or let him do his time without the hard labor. After protests, he was finally released about halfway through his sentence. He died six months later, never bitter or angry. Two years later, the first black students were admitted to the school that had refused him entry.

8 Juliette Hampton Morgan

A true Southern belle, socialite, and highly educated white woman, Morgan had all the advantages of wealth and prestige. However, her one glaring weakness led to her involvement in the Civil Rights movement. Morgan, besieged by nerves and anxiety, couldn’t drive—so she rode the city buses in Montgomery, Alabama. She became incensed at the horrible treatment of black passengers and stood up for them at every opportunity. A librarian, she began writing letters to the local newspaper, advocating fair treatment of black people. As a result, she became a target of all manner of attacks, including taunting at work, mocking by bus drivers and white passengers, and public humiliation. The situation escalated when a cross was burned into her lawn.

When she continued to write, she received numerous death threats and attempts to have her fired. She ultimately could not withstand the assaults: She resigned her post on July 15, 1957, and was found dead the next morning from an intentional overdose of pills. Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote of her in his book, Strive Towards Freedom: The Montgomery Story, saying that she was the first to draw parallels between the movement and Gandhi in her letters to the editor. She was inducted into the Alabama Women’s Hall of Fame in 2005, nearly 50 years following her death.

7 Rev. James Reeb

Reeb, a white Unitarian minister working in a poor black neighborhood in Boston, was one of the many who heeded Dr. King’s call for clergy to join him in Selma for the march to Montgomery. Reeb, 38, was a father of four and wholly committed to the cause of civil rights. While in Selma, he and two other white ministers left a diner and were accosted by a trio of white men. Reeb was beaten with a club and slipped into a coma, dying the following day.

Reeb’s death, along with the murders of Jimmie Lee Jackson and Viola Liuzzo, brought such intense light to the darkness of violence and hatred in the South that on the evening of Reeb’s memorial service, President Johnson made a special plea to Congress to move on the Voting Rights Act. The act was passed later that summer.

6 Jonathan Myrick Daniels

A seminary student at Episcopal Divinity School in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Daniels was yet another clergyman who responded to King’s plea for advocates to attend the planned march from Selma to Montgomery. While participating in a demonstration at Fort Deposit, Alabama, Daniels and 22 others were arrested and transferred to the county jail in nearby Hayneville. Released on August 20, Daniels, along with Catholic priest Richard Morrisroe, accompanied two black teenage girls (who had also been in jail for the protests) to a nearby store.

On the porch of the store, a construction worker and part-time deputy pulled out a shotgun and pointed it at 17-year-old Ruby Sales. Daniels knocked Sales to the ground and took the shot. The Catholic priest was seriously wounded, and Sales’s life was saved. Dr. King said of Daniels, “One of the most heroic Christian deeds of which I have heard in my entire ministry was performed by Jonathan Daniels.” Sales went on to become a nationally recognized civil rights activist, and founded the Spirit House, an organization which works on social, economic, and racial justice issues with a spiritual approach.

5 Viola Gregg Liuzzo

Liuzzo is among the 40 martyrs of the Civil Rights movement honored in the Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery, and has the sad distinction of being the only white woman to be murdered during the movement. A Detroit wife and mother to five, Liuzzo was involved in civil rights as a member of the Detroit chapter of the NAACP. She went to Alabama to take part in the march from Selma to Montgomery, and helped out by driving supporters between the two cities.

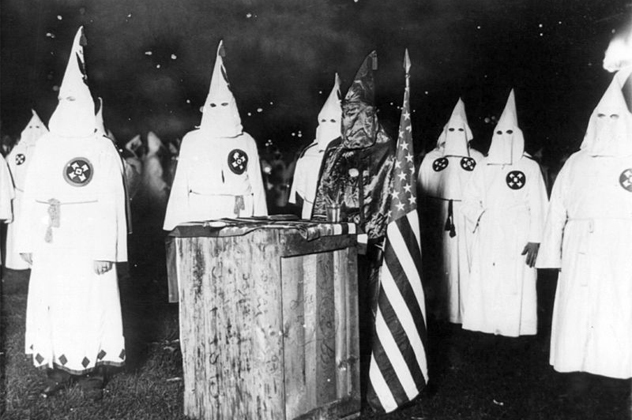

On the evening of March 21, 1965, she was driving a black teenager named Leroy Moton—a young member of the SCLC—to Selma when a car pulled alongside them on Highway 80. A passenger in the car shot into Liuzzo’s car, killing her. Moton survived by playing dead. Over 300 people attended her funeral, including Dr. King, US Attorney Lawrence Gubow, Jimmy Hoffa, and the United Automobile Workers Union President. Her death prompted President Johnson to launch an investigation into the KKK.

4 Vernon Dahmer

Born in 1908, Dahmer was a businessman in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, where he owned a few businesses, including a sawmill and a small grocery store, which was adjacent to the family home. He was president of the local NAACP chapter, and focused on getting black citizens registered to vote. On the eve of his death, in January 1966, he announced on a radio station in town that he would allow people to pay the poll tax at his store so they wouldn’t need to travel to the courthouse. He even made the offer to pay the $2 poll tax for anyone unable to afford it.

The following evening the Dahmer family was awakened to the sound of three carloads of Klansmen pushing into their house, shooting and setting fire to a dozen one-gallon containers of gasoline. His wife, youngest children, and elderly aunt all escaped, although his daughter was severely burned. Vernon Dahmer succumbed to his injuries just 12 hours later. Dahmer’s four eldest sons were all away as part of the US military at the time of the firebombing. Four men served less than 10 years for the crime, while nine others went free. One man, the mastermind of the atrocious attack, remained free until his fifth trial in 1998, when he was sentenced to life. He died in prison in 2006 at the age of 82.

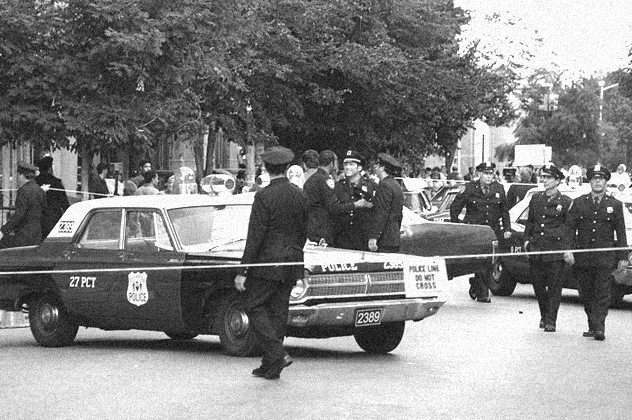

3 Oneal Moore

On June 2, 1965, Oneal Moore was marking his one-year anniversary as the first African-American police officer in Washington Parish in Louisiana. Oneal and his partner, Creed Rogers, a black officer who began his appointment at the same time as Moore, were on their way to Oneal’s home to eat dinner together at the end of their shift. They were in their patrol car when a pickup truck with three men inside approached the officers. Shots were fired, and one hit Moore in the head, killing him instantly, while another struck Rogers, blinding him. No one was ever formally charged, despite the case being reopened three times by the FBI.

The prime suspect died in 2003. Moore’s widow remains in Hattiesburg, still residing in the same home she kept with her husband. Moore also left behind four daughters, aged nine years down to less than a year of age. In 2013, a memorial was planned in Moore’s honor, and also to remember all the other fallen police officers from the area.

2 Rev. George Lee

Rev. George Lee was born in Mississippi and became a pastor at a church in the town of Belzoni in the ‘30s. He was active in civil rights and involved in the NAACP, often using his pulpit to encourage his black congregation to become registered voters. Lee also used a printing press he owned to further the cause. Lee was offered protection by white officials on the condition that he removed his name from voting lists and stopped encouraging other African Americans to become registered voters. He refused. Lee died on May 7, 1955 under suspicious circumstances.

Witnesses reported seeing several white men fire a shotgun into Lee’s car, and the tires on Lee’s car were found lacerated with shotgun pellets. More pellets were found in his face during the autopsy. However, the sheriff insisted that they were mere dental fillings, although fillings were not made with lead. Sheriff Shelton declared his death accidental, and the governor refused to allow further investigation. Nobody was ever charged with Lee’s murder, and the official cause of death was listed as an accident.

1 Harry And Harriette Moore

The only couple murdered during the Civil Rights Movement, the Moores were killed on Christmas Day in 1955 when a firebomb placed directly under their bedroom detonated with enough force to send their bed through the rafters of their home in Mims, Florida. Both of the Moores were educators and deeply involved in the NAACP, focusing especially on the issues of black and white educator salaries and segregation. Later, Harry Moore moved his focus to a much more controversial and dangerous topic: police brutality and lynchings.

Due to their involvement in these issues, the couple lost their jobs in the schools and, eventually, their lives. Harry died in the initial blast, while his wife died nine days later. The couple left behind two daughters. While the blast was initially called “the bomb heard round the world” and spurred all kinds of rallies and letters to the governor and president, all these years later, their legacy has been left largely untended and untold. Nobody was ever charged for the murders of the Moores.

Katlyn Joy is a freelance writer living in Denver, CO. She tutors students in history and language arts, and is a mom to seven children. She has a passion for helping others remember those heroes of the movement who may become lost history.