Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

10 Striking Pictures From World War I

The so-called Great War is remembered as a glorified, patriotic adventure for freedom. These 10 pictures represent the tragedy, bloodshed, and significance of the war for what it truly was to those living at the time.

10Bomb Crater In West Flanders

This remarkable color photograph was taken during the Battle of Messines, which occurred in West Flanders, France in early June 1917. The battle lasted for a week, with over 25,000 confirmed killed and 10,000 missing. The colossal crater seen in the photograph was created on the first day of the battle by the British Second Army when they detonated 19 different mines in 19 seconds, followed quickly by a heavy artillery barrage. Five other mines remained undetonated, and a sixth was detonated during a thunderstorm in 1955. Over 10,000 German soldiers died in the blast, which is said to have been heard all the way from London and Dublin.

The attack was the largest planned explosion in military history at the time and created very dangerous territory, even for the British. Overcrowding on the edge of the ridge resulted in the deaths of approximately 7,000 British soldiers. Many of the craters created during the Battle of Messines can still be seen on French farms and have been transformed into pools.

9Prosthetic Faces

The incredibly unsettling wall of the shop shown in this picture belonged to Boston-born Anna Coleman Ladd. The first of its kind was actually the “Masks for Facial Disfigurement Department” (located in a London hospital), but soldiers called it the “Tin Noses Shop.”

An incredible 21 million men were wounded during World War I, and many returned with crippling facial injuries. Although plastic surgery was advancing quicker than ever before, many men used prosthetic faces to hide the scars that could not be removed. After working with wounded soldiers with the Red Cross, Anna set up her own studio in Paris, which became incredibly popular. The faces were handmade from copper and applied to the patient’s face during painting so that it would blend in with their skin as perfectly as possible.

The Tin Noses Shop had produced over 220 prosthetic masks by 1918. Ladd attempted to make her shop as cheery as possible to combat the trauma that the patients had already been through—the ivy-covered garden was decorated with statues, the rooms were filled with flowers, and the walls were hung with flags. Soldiers were given chocolate, wine, and dominoes to occupy themselves. The well-loved shop set revolutionary standards of care for soldiers that were unlike anything they had seen before.

8Lieutenant Norman Eric Wallace

Lieutenant Norman Eric Wallace was a Canadian observer during World War I. He enlisted in 1915 and was immediately sent off to Europe. Two years later, Wallace’s plane crashed into the ground, and he suffered terrible facial injuries due to severe burns.

The plastic surgery used to reconstruct Wallace’s face was revolutionary at the time. Grafts of skin taken from his buttocks were used to repair the scarring, and skin from around his neck and chin was moved to cover them up. Surgeons used pedicle tubes to lift skin from his shoulder to cover his cheeks and upper lip. Wallace also had to use a prosthetic face.

Despite this ordeal, he fell in love during his hospital stay and married in 1920. Tragically, his wife died of cancer just a few days before their first wedding anniversary. Wallace continued his military career and was eventually promoted to major. He lived until late 1974, when he died of lung cancer. He spent most his life staying alone at hotels and chalets in Llangammarch Wells, an isolated village in Wales, where he was loved dearly by the locals.

7View Of Verdun After Seven Months Of Bombing

The Battle of Verdun, which took place near the city of the same name near the Meuse River, lasted just under 11 months. This picture shows the effect of military bombardment on the then-abandoned city. The destruction was caused by the questionable tactics of attrition warfare used by both sides, intended to destroy as many resources and kill as many people as possible, effectively wearing down the enemy.

It is estimated that over a million men died during the Battle of Verdun, but this picture clearly shows the effect that the war had upon the lives of civilians caught up in the conflict. This attack was a particular blow to the French, as Verdun was of historic importance to them—many other significant battles had been fought there, and it had been known throughout history as a thriving trade center. Its targeting was intended to “bleed France white.” In other words, German Chief of Staff Falkenhayn’s main objective was to create a bloody killing ground rather than gain any strategic grounds.

6Used Artillery Shells

The form of fighting used in the Great War had never been seen on such a large scale. One example is the aforementioned Battle of Verdun. On the first day of that battle alone, German forces used 1,200 artillery guns, 2.5 million shells, and 1,300 ammunition trains to attack their Allied foes. Daily supply shipments weighed up to 25,000 tons, and when the 300 days of fighting came to an end, German artillery units had been so worn out that they had reverted to using flamethrowers. Overall, 14 million shells were fired in the Battle of Verdun alone.

This picture shows a pile of shells spent during the course of a single day. It illustrates how so many men were killed and injured during the war. One of the reasons for such heavy casualties during the war was the use of the “creeping barrage,” a tactic masterminded by Sir Henry Horne and first used in the Battle of the Somme in 1916. This strategy involved slowly moving artillery fire forward just in front of advancing troops. It could be very dangerous, because if the timing was wrong, it could easily kill one’s own soldiers.

5British Supply Sledge Pulled By Reindeer In Russia

In 1914, Russia was an Allied force, helping the British to fight Germany. However, three years later, they were forced to pull out of the war effort. This photograph of a British soldier pulling a sledge of supplies through snow-covered Russia with reindeer illustrates how, despite massive advancements in technology, many of the tactics used in World War I were archaic and probably resulted in more deaths than they prevented.

Russia wasn’t the only country using outdated methods—the British still relied upon a horseback cavalry, which largely failed against Germany’s machine guns and artillery. It often took those in charge a few years to figure out that certain tactics weren’t working—the last British cavalry charge occurred during the Battle of the Somme in 1916, two years after the war had started. These attacks were very costly, and the combinations of barbed wire, deep mud, and heavy artillery fire did not work well with the use of animals. The introduction of the tank later that year finally ended their exploitation.

4The Crucifix

This image is one of the most remarkable photographs of the war seen in recent years, yet these photographs were not taken by a professional or assigned photographer. They were taken with a Contessa camera by 16-year-old Walter Kleinfeldt, who had joined the war just a year earlier. Walter later set up a photography shop when he returned to Germany, but this photograph, which was taken during the Battle of the Somme, was not discovered until almost 100 years later, when it was found by Walter’s son.

The contrast between the dead soldier and the untouched crucifix is striking. In a BBC documentary about the collection from which it’s taken, Walter’s son argues that the photograph is “like an accusation against war.” Some of Walter’s other photos include a picture of the bodies scattered over no man’s land titled “After the Storm” and another of a German medical officer comforting a soldier in his last moments. Kleinfeldt’s images also capture the everyday life of soldiers when they were away from the battlefield, washing in rivers and wandering around German towns.

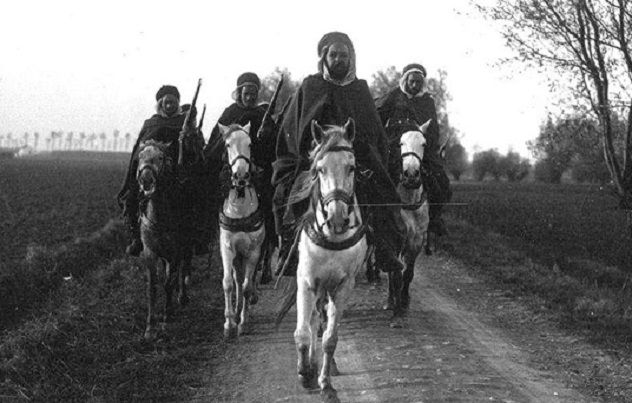

3French Colonial Troops

Although it seems obvious, the fact that the conflict was truly a “world” war is often taken for granted. This stunning photograph was taken by Albert Kahn, a millionaire banker who spent the early 20th century capturing the customs and cultures of countries across the globe in remarkable color photographs for his book The Archives of the Planet. During these years, it was inevitable that Kahn would encounter the war.

This photograph shows a group of French Colonial Cavalry Soldiers from the Fourth Spahi Regiment who were apparently from Morocco. In 1914, the French had seven Spahi regiments. All of them saw war on the Western Front, but their role as great cavalry fighters became less relevant as trench warfare became more regular. The use of colonial troops was particularly heavy in France, most likely due to their small population.

By the time the war broke out, Europe had conquered a vast majority of the rest of the world. India volunteered the most men at 1.5 million troops, while New Zealand, Canada, South Africa, and Australia contributed millions more to the British military. The French had the support of the West Africans, Indochinese, and Madagascans. The result was a war that touched more corners of the world than any other had before.

2Australian Soldier Carries Comrade

This poignant photograph depicts an Australian soldier carrying a wounded comrade down Suvla Bay in an attempt to get him medical treatment. The Battle at Gallipoli was one of the first heavy losses for the Australian army, and it impacted them greatly. It is commemorated every year on April 25, known as ANZAC Day.

The Gallipoli campaign’s main objective was to capture Constantinople from the Ottoman Empire, but it failed. It is thought that nearly half a million men died in this campaign alone. The brutality of the battle is depicted in one of Australia’s most famous songs, “And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda” by Eric Bogle. Ultimately, the Australian military suffered nearly 27,000 casualties, nearly two-thirds of the three divisions that were sent there.

The significance of the battle to Australian history is perhaps summed up best by the Prime Minister at the time, William Hughes, who said that the fledgling country “was born on the shores of Gallipoli.” Even today, despite the fact that the Australians suffered much heavier losses on the Western Front in a space of seven weeks than they did during eight months at Gallipoli, it is still remembered much more enthusiastically than any other battle of the war.

1Pyramid Of German Helmets

The pyramid in this picture is one of two astounding “victory” structures that were composed in New York City, towering over both ends of “Victory Way” near Grand Central Station during 1918. Each pyramid, made up of 12,000 German helmets, was carefully handcrafted and designed by appointed artists. Each helmet represented a captured or dead German soldier, and the pyramid represented the defeat of the enemy.

The displays, which showed up along with captured German artillery, were a way of advertising war bonds. Supposedly, the helmets would be given away to those who invested in the war. Their whereabouts today are unknown.

Although it may seem bizarre or even wrong to us now, taking souvenirs from battle was commonplace during the 20th century despite being banned in many units. If you think that a collection of 24,000 dead soldiers’ helmets is creepy, imagine the shock on one young boy’s face when his Australian father brought back the mummified head of a Turkish soldier he had killed in Gallipoli.

Michelle is a student and, according to her sister, a Disney princess. Feel free to ponder on her other musings at elizabethwritesstuff.blogspot.co.uk.