Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Terrifying Facts About Gulags

The USSR during the Stalin era was a place of purges and bloodthirsty secret police where the most innocent remark or unfounded suspicion could land you in a gulag. “Gulag” is an acronym for Glavnoe Upravlenie Ispravitel’no-trudovykh Lagerei, which translates to “main administration of corrective labor camps.” There were dozens of these forced labor camps spread across the nation, many of which were located in the some of the coldest places on the planet. While not “extermination camps,” life in the gulags was unrelentingly brutal.

10The Kengir Uprising

To understand the Kengir uprising, it is important to note that gulags generally did not contain the large populations of rapists, murderers, and drug dealers of today’s prisons. The vast majority were political prisoners, intellectuals who took a stand against the government’s oppressive regime. They were arrested under Article 38, a sweeping penal code that called for the arrest of anyone suspected of counter-revolution. The guards used “real” criminals (called “thieves”) as a means of controlling the wider gulag population. The thieves terrorized activists, preventing them from organizing.

In May 1954, the same tactic was attempted at Kengir, a gulag in the Kazakh SSR, when approximately 650 thieves were admitted to a population of over 5,000 activists. The plan backfired, and soon after, the prisoners took control of the camp, driving out the guards. Far from descending into anarchy, the inmates took full advantage of their freedom, building their own society complete with wedding ceremonies, plays, and an improvised hydroelectric power system. Knowing that they couldn’t hold the gulag for long without defending themselves, they made all kinds of weapons, including crude IEDs.

Negotiations between the prisoners and the outside world soured, and 40 days into their uprising, the Red Army stormed in with tanks, attack dogs, and 1,700 troops. The prisoners put up a valiant fight, but their rebellion was crushed. Some of the defeated inmates committed suicide, fearing what might happen to them if they were caught. The official government death toll numbers mere dozens, but survivors reported that hundreds were killed.

Read the whole history of these horrifying labor camps in Gulag: A History at Amazon.com!

9The White Sea Canal

Slave labor has its benefits, and the gulags aimed to make good use of their prisoners on various construction projects across the USSR. One of their first major undertakings was the White Sea Canal, built in 20 months between 1931 and 1933. The 227-kilometer (141 mi) canal connects the White Sea to Lake Onega. Even with modern tools, this would have been a massive undertaking, but the canal was largely dug with primitive tools like shovels, pickaxes, and wheelbarrows. The death toll of this project is unknown, but historians estimate that anywhere between 25,000 and 100,000 lives were lost in the process.

What makes the construction of the White Sea Canal even more tragic is that it was largely useless. Not only were prisoners used for building it, the engineers were prisoners, too. Their creation was too shallow to be used by large ships, and it was choked with ice for half the year. The prisoners certainly didn’t take any pride in their work—they merely did what they had to do to survive—and the canal was so poorly constructed that by the time it was finished, it was already starting to fall apart.

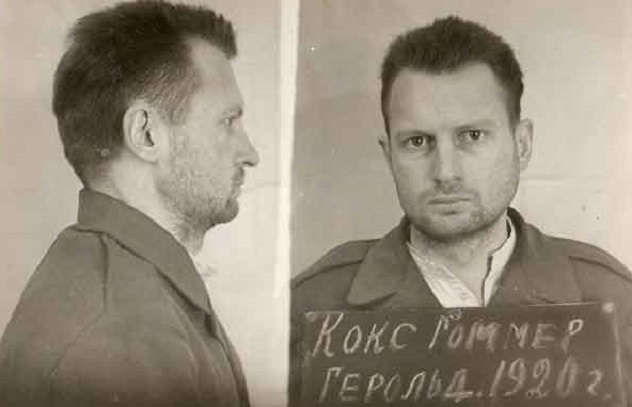

8John Birges

There are very few stories of escape from the gulags. Weakened by hard labor and starvation diets, prisoners had no energy to make such attempts. Even if they were successful, many of the camps were so remote that there was virtually no chance of making it back to civilization. Hungarian John Birges would beat this trend, however. He was not the best-known resident of the gulags, but he did leave a bizarre legacy.

Born in 1922, Birges served in the German Luftwaffe during World War II. After he was captured as a prisoner of war by the Russians on April 27, 1948, he was sentenced to 25 years of hard labor in a Siberian gulag. He would only serve nine, becoming one of the rare people to escape in 1954 after building a bomb and exploding his way out. In 1957, he immigrated to the United States and built up an extremely successful landscaping business.

Unfortunately, Birges had a serious gambling problem. He blew hundreds of thousands of dollars at Harvey’s Resort Hotel, a casino in Stateline, Nevada. In 1980, he decided to get it back, using the same technique that served him so well in the gulags. He dreamed up a harebrained scheme to build a bomb and position it inside the casino, threatening to detonate it unless he was paid $3 million in a remote drop. On August 26, he and two hired henchmen sneaked into the casino, pretending to deliver a copy machine, and rolled a bomb containing nearly 450 kilograms (1,000 lb) of dynamite into the hotel along with their demands.

The drop was never made, and the police decided to attempt disconnecting the detonator with a charge of C4. The plan didn’t work, and the bomb blew a massive crater in the hotel. Birges’s bomb was practically unbeatable, but he was no criminal mastermind. He was picked up and spent the rest of his life in prison.

7Leon Theremin

Leon Theremin was born in St. Petersburg, Russia in 1896. He’s best known for his accidental invention of the musical instrument that bears his name, the theremin, which produces an unnatural, warbling sound and was frequently used in sci-fi movies like 1951’s The Day The Earth Stood Still. By 1920, he began performing concerts with his instrument, which led to touring Europe and eventually the United States, where he performed at Carnegie Hall in 1928.

Theremin lived in the US for a decade, returning to the USSR in 1938 due to financial woes and concerns about the impending war. He was arrested and sent to the infamous Butyrka Prison in Moscow, then to work in the Kolyma gold mines. Somewhere along the line, it was determined that his talents were being wasted on manual labor, so he was sent to work at a secret laboratory called a sharashka, where he was tapped to develop eavesdropping devices to be used by the secret police. He was particularly successful in this venture, developing the Buran eavesdropping system, a crude laser microscope that used an infrared beam to detect sound vibrations against glass windows. It was used to spy on foreign embassies in Moscow.

Another of Theremin’s inventions was a device dubbed “The Thing.” One of the first “bug” microphones, it was ingeniously hidden in a wooden carving of the Great Seal of the United States, which was presented to the US Ambassador to the USSR by Soviet schoolchildren in 1945. It wasn’t discovered until 1952. Theremin was freed from the sharashka in 1947 but worked with the KGB until 1966. He died in 1993 at age 97.

6Alexander Dolgun

You wouldn’t wish the life of Alexander Dolgun on your worst enemy. Born in the US, his father traveled to the USSR for work at the Moscow Automotive Works. He brought his family, but when they later tried to return to America, they weren’t allowed to leave. The Dolgun family was held prisoner through some of the worst times in Russian history, including the Great Purge and World War II. Alexander began working at the US Embassy as a file clerk at age 16.

Suspecting he was part of some conspiracy, the Soviet State Security arrested him in 1948. He was viciously tortured, starved, beaten, and subjected to sleep deprivation for over a year at Lefotovo Prison in Moscow. He was then transferred to Sukhanovo Prison, where the campaign of terror continued. He claimed that “the beatings went on every day except Sunday.” The US was aware of his predicament but did nothing to help due to Cold War tensions. While Dolgun was imprisoned, his parents were also tortured, eventually driving his mother to insanity.

Dolgun maintained his own sanity by singing songs and remembering old movies and lessons. Eventually, it was determined that he had no hand in espionage, and he was sent to a copper-mining gulag in Dzhezkazgan, Kazakhstan. He was released from the gulag after the death of Stalin and eventually made his way to America in 1971 with his wife and son. Many of Dolgun’s experiences were included in Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago, and he penned his own memoirs in 1975. He died in 1986 at age 59.

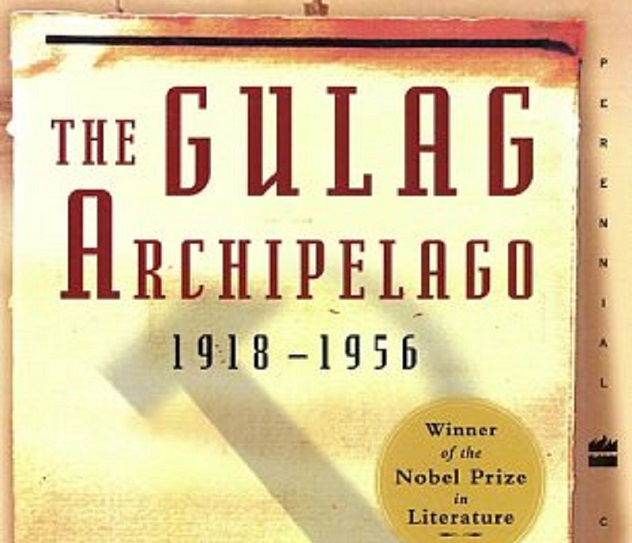

5The Gulag Archipelago

The Gulag Archipelago is a three-volume book published in the West in 1973 detailing the gulag system. Written by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who was himself imprisoned, this book gave many people their first real glimpse of what life was like in the Soviet Union. Along with his exhaustive research, Solzhenitsyn waxes philosophical, pontificating on the nature of evil in the human soul.

The Gulag Archipelago is a three-volume book published in the West in 1973 detailing the gulag system. Written by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who was himself imprisoned, this book gave many people their first real glimpse of what life was like in the Soviet Union. Along with his exhaustive research, Solzhenitsyn waxes philosophical, pontificating on the nature of evil in the human soul.

Solzhenitsyn’s reports left him perpetually under observation by the KGB. They did everything in their power to get their hands on his work, including torturing one of his typists, Elizaveta Voronyanskaya, who gave up the location of one of the manuscripts in September 1973 before hanging herself. Solzhenitsyn himself was arrested in February 1974 and exiled to West Germany, eventually settling in the US.

Not surprisingly, it was difficult to get the book published in the USSR. It was circulated for years in underground samizdat publications before appearing in part in a Russian literary journal called Novy Mir in 1989. Today, The Gulag Archipelago is required reading in Russian schools. Solzhenitsyn returned to Russia after the fall of the Soviet Union and died in Moscow on August 3, 2008, at age 89.

4Starvation

Not surprisingly, the gulag prisoners were not well fed. Their paika, or ration, was dependent upon how much work they performed. Even the hardest-working inmates barely received enough to survive, and consistent under-performance would invariably result in starving to death.

Author V.T. Shalamov, who spent over 20 years in the gulag system, would later pen a series of short stories called Kolyma Tales, in which he detailed their ravening. “Each time they brought in the soup . . . it made us all want to cry,” he wrote. “We were ready to cry for fear that the soup would be thin. And when a miracle occurred and the soup was thick, we couldn’t believe it and ate as slowly as possible. But even with thick soup in a warm stomach, there remained a sucking pain; we’d been hungry for too long.”

Those withered souls on the brink of death were called dokhodiagas, or goners. In a 1938 letter from USSR procurator Andrei Vyshinsky to NKVD chief Nikolai Yezhov, Vyshinsky laments the conditions of these men, stating “Among the prisoners there are some so ragged and lice ridden that they pose a sanitary danger to the rest. These prisoners have deteriorated to the point of losing any resemblance to human beings. Lacking food they collect [garbage] and, according to some prisoners, eat rats and dogs.”

Unfortunately, these conditions would constitute a paradise compared to what happened after the German invasion of the USSR in June 1941. Nearly all the nation’s resources were diverted to the front lines, and death rates skyrocketed as food and medicine became scarce, if not wholly unavailable. Scattered reports, including those penned by Solzhenitsyn, indicate that cannibalism did occur on occasion.

Labor camps like the USSR’s gulags are still frighteningly common today. Read the harrowing story of one man’s escape from a North Korean camp in Escape from Camp 14: One man’s remarkable odyssey from North Korea to freedom in the West at Amazon.com!

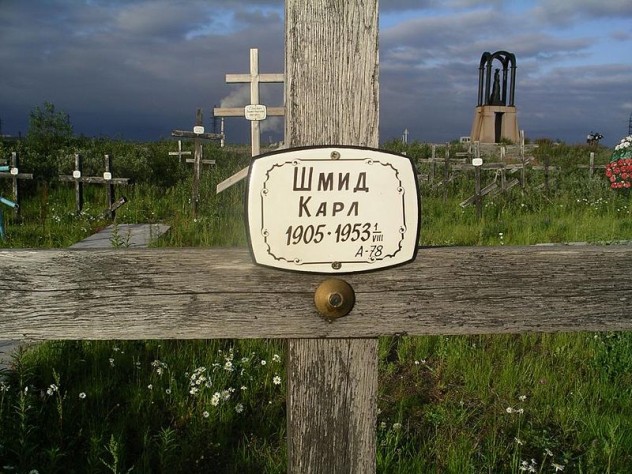

3The Death Toll

Unraveling the secrets of the USSR is a task equal to counting every grain of sand on Earth. The gulags are no exception. Records were destroyed or falsified to the point where all we really have are the wildly varying estimates of historians. Solzhenitsyn himself indicated that he believed around 50 million people had been held in gulags, with others estimating one-tenth that many.

Unlike Germany’s Auschwitz, the gulags were not death camps. Human life was certainly treated dismissively in the gulags, but their intention was not to liquidate the population. Instead, they were designed to serve the dual purpose of building the nation’s infrastructure, which was incredibly primitive outside of the eastern cities, and confining those who might cause trouble for the totalitarian government. However, declassified Soviet data seems to indicate 1,053,829 people died in the gulags between 1934 and 1953, a disturbingly specific number. It was almost certainly more, as gulags had a habit of releasing prisoners who were on the verge of death rather than dealing with the logistics of handling their corpses.

2The Bitch Wars

It’s debatable how much honor there is among thieves, but in the USSR, criminals were expected to keep their mouths shut and never collude with the government or police. Soviet casualties during World War II were vast, with some sources claiming over 10 million lives were lost. Grievously shorthanded, the government struck deals with many of the prisoners in the gulags to fight on the front lines for a reduction in sentence.

This was against the “thieves’ code,” which forbade serving the government in any way, even to take up arms and defend the country. When these men returned from war, they were considered suka, or “bitches,” and were regularly targeted by other inmates in a campaign called the “Bitch Wars.” The authorities ignored their deaths, content to let the criminals kill each other and ease the already tight resources of the camps. These deaths were often unrelentingly brutal, such as crushing each other’s skulls with bricks and shovels.

1North Korea’s Gulags

The USSR officially dissolved their gulag forced labor program in 1960, but forced labor camps are by no means a thing of the past. North Korea is particularly well known for the horrible conditions of its prisons, such as Camp 22, where prisoners are routinely worked under the threat of being beaten and tortured to death. Starvation is the norm here—inmates feast on snakes, frogs, and rats, and even pick through animal dung for seeds to bolster their meager diet of porridge.

In 2014, the UN issued a report on the myriad human rights violations occurring in North Korea. One of the testimonials in the report belongs to Kim Kwang-Il, a 48-year-old man who defected after spending three years in a gulag for the grievous crime of smuggling pine nuts across the border. Kim published a book about his ordeal and produced drawings of the tortures he saw perpetrated in the gulag, including men forced to adopt agonizing positions and hold them until they filled a glass below them with sweat.

Mike Devlin is an aspiring novelist.