Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Witch Gods and Goddesses From Around the World

Wicca, like any other religion, has myth and folklore galore. For centuries, the gods and goddesses of witchcraft have had their tales spread far and wide by their worshipers. Some of these deities are benevolent—others, not so much.

10Abonde

Germanic/Central European

Abonde (also known as Perchta) is not just a Wiccan goddess—she’s one of the main archetypes for many of our favorite fairy tales. She inspired fairy godmothers, wicked stepmothers, Snow White, and even Tinkerbell.

Abonde is the Winter Goddess—one of the most important figures in all of Wicca in Europe. Some believe that she arose from the earliest divine female guardian figures from ancient hunting cultures. Her association with witchcraft and witches may well have originated before the medieval witch trials—this provides evidence that witches existed long before people grew frightened of them.

Like many goddess figures, her appearance changes depending on her story and temperament. She can appear as a beautiful young maid in a flowing white dress or a wizened and shriveled old crone with wolf fangs and glowing red eyes. As the young lady in white, she brings fertility and prosperity—if crossed, however, the crone will bring forth misery, illness, and death.

Today, many Wiccans revere her as one who leads nocturnal hordes of merry witches through the air, stopping at households to eat and drink of the feasts set out for them. She and her fellow witches bestow prosperity to the generous and deny their blessings to the miserly who left nothing.[1]

9Aradia

Italian

According to tradition, Aradia is either an Italian witch or a goddess who came down to Earth. She was “born” in 1313 in Volterra, a town in northern Italy. There, she lived and taught throughout the latter half of the 14th century, speaking of an “Age of Reason” that would soon replace the “Age of the Son.”

In 1890, author and folklorist Charles LeLand published Aradia: Gospel of the Witches, based around a document he called “the Vangel,” which was supposedly given to him by a woman named Maddalena. Its authenticity was in dispute right from the beginning, but it has since become a wildly popular foundational Wiccan document.[2]

Leland’s account described an Italian legend—that may be partially true—of a woman who, “traveled far and wide, teaching and preaching the religion of old times, the religion of Diana, the Queen of the Fairies and the Moon, the goddess of the poor and the oppressed. And the fame of her wisdom and beauty went forth over all the land, and people worshiped her, calling her La Bella Pellegrina (the beautiful pilgrim).”

This narrative may refer to a sect called the Guglielmites, who believed in a “Guglielma of Milan”—the daughter of the king of Bohemia and the female incarnation of the Christian Holy Spirit. The sect itself was characterized by social and gender equality—they even elected their chief, a woman named Maifreda da Pirovano, as their female pope. This theme of a female messiah (and female empowerment in general) and enlightened equality may have inspired the Aradia legends.

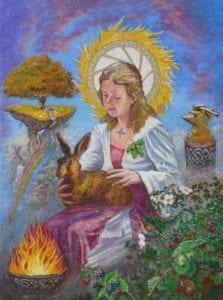

8Brigit

Celtic

Brigit was a goddess of pre-Christian Ireland. She appears in Irish mythology as a member of the Tuatha De Danann. Brigit is considered the patroness of poetry, smithing, medicine, arts and crafts, cattle and other livestock, sacred wells, serpents, and the arrival of early spring. The Celtic people have worshiped her as a Saint for over fifteen hundred years and as a Goddess long before the Roman invasion of Britain and the birth of Christ. Her cult was so powerful that the Celtic Christian Church had to adopt her as a Saint, and the Roman Catholic Church followed suit, for her people would not abandon her. Along with St. Patrick, she is the patron Saint of Ireland. St. Brigit is often referred to as Muire na nGael or “Mary of the Gael.” Her name is spelled in a myriad of ways, including Brigid, Brigit, Brighit, Brid, Bride (Scotland), Ffraid (Wales), Brigantis (Britain), Brigando (Switzerland), Brigida (The Netherlands), Brigantia, among others.

The name “Britain”’ is a derivation of Brigit’s name. Britain was named for an ancient Celtic tribe, the Brigantes, who worshipped Brigit and were the largest Celtic tribe to occupy the British Isles in pre-Roman times. The tribe initially came from the area that is now Bregenz in Austria near Lake Constance. The word ‘brigand’ comes from this tribe of fierce warriors.

Her worship probably spread from the Continent, leaving place names behind, such as Brittany in France. Brigit place names are found in Brechin, Scotland, the River Brent in England, the river Braint in Wales, Bridewell in Ireland. Even London has a Bridewell. The symbol of Britain—the Goddess Brigantia or Britannia (still found on their fifty-cent coin), is Brigid in her aspect as Goddess of Sovereignty or Guardian of the Land.[3]

7Leonard

Germanic

Despite his plain-sounding name and lack of divinity, Leonard is the demon inspector-general of sorcery, black magic, and witchcraft. Sometimes called “le Grand Negre” (the Black Man) due to his face being black as night, Leonard’s duties make him the grandmaster of the witches’ Sabbaths.

Collin de Plancy’s 1863 Infernal Dictionary describes him as having a goat’s body from the waist up, three horns on his head, a goat’s beard, ears like a fox, and inflamed eyes. He also has a face on his posterior, which witch hunters claimed existed so witches could kiss it in adoration during their evil gatherings. Leonard can also take on the forms of a bloodhound, a blackbird, or a tree trunk with a gloomy face.[4]

The Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (1898) writes that Leonard is also a grandmaster of the nocturnal orgies of demons and that he marks the initiates “with one of his horns.” So, if you hear howling in the woods at night, don’t go investigating.

6Cernunnos

Celtic British

Cernunnos (which is Celtic for “Horned One”) is the male aspect of nature. He is known as the “lord of wild things”—associated with animals, good fortune, abundance, material wealth (as symbolized by a coin purse that he carries), and virility.

He’s usually depicted as wearing antlers and being accompanied by a stag or an antlered serpent. The earliest depictions of him were found in northern Italy, but he was primarily worshiped throughout Gaul by names now lost, spreading throughout Celtic Britain and into Ireland.

Worship of Cernunnos goes way back—it is believed that cults devoted to him existed in prehistory and the earliest goddess figures in Celtic mythology. His name comes from a stone carving in Paris dating back to the Gallo-Roman period. In very early Irish literature, he was called “Uindos.”

In their efforts to stamp out paganism, the Romans first associated him with their god Mercury. Later, they attached him to Herne, a trickster from medieval legends. When that didn’t work, they turned his appearance into a symbol of pure evil—some contend that his look was the inspiration behind the Christian devil, Satan.

New pagan and Wiccan beliefs contend that he is continuously “born” at the winter solstice, marries the moon-goddess Beltane, and dies again at the summer solstice in an endless cycle of death and renewal. Because of that, he is considered an important part of modern witchcraft, with many male Wiccans adopting him as their own.[5]

5Oya

African

While many African tribal men are highly respected as practitioners of medicine-related magic, women who do so are more often viewed with suspicion, if not considered downright malevolent. The Yoruba, for example, believed that some witches (called aje) would transform themselves into birds and fly by night to practice magic far from prying eyes. These witches were granted these powers by the great feminine spirits known as the Orisha.[6]

One of the most powerful Orisha was Oya–the goddess of storms, winds, rainbows, thunder, and a water goddess of the Niger River. She is a fierce warrior who protects women and is associated with change. Oya is especially known for using charms and magic and is known as the “Great Mother of the Elders of the Night.”

Oya is the oldest sister to the goddesses Yemaya and Oshun, and she is considered the crone figure in this trilogy of feminine goddesses. Under the name of Yansa, she also figures in Haitian Voodoo as one of over 400 Orisha spirits.

4Cerridwen

Welsh

In early Welsh tradition, Cerridwen was the goddess of inspiration and the “mistress of the cauldron”—a dark prophetess associated with inspiration and poetry. She was considered both a mother and crone figure.

The cauldron—hers of which could raise the dead—was an important aspect of Celtic life, serving as both a household hub and as a tool for divination and sacrificial rituals. This would explain the common connection between cauldrons and witchcraft. In addition to Cerridwen, the ancient Gauls linked cauldrons to the god Taranis, and one of Ireland’s four revered magical artifacts was the Great Cauldron of Plenty—a cauldron that gave everlasting food and drink to those worthy of it.[7]

Cerridwen gave birth to two children: a beautiful daughter and a hideous son named Afagddu. To compensate for her son’s ugliness, she used her cauldron to brew a potion. The first three drops would confer great wisdom, while the rest would be a deadly poison. As the time drew near to make use of it, a servant named Gwion Bach was stirring the pot when three drops fell upon his thumb. Without thinking, he put his thumb to his mouth to cool and clean it.

Bach fled the instant that he realized his mistake, but an enraged Cerridwen pursued him. Using powers conveyed by the potion, the servant attempted to escape by changing into various forms (each one symbolizing the changing seasons). Cerridwen thwarted his escape plans each time until finally, he changed into a grain of wheat and was eaten by the goddess (who had conveniently transformed into a black hen). However, this didn’t kill Bach—amazingly, Cerridwen became pregnant with him and rebirthed him as the great bard, Taliesin.

Cerridwen and Taliesin are linked to Arthurian legend, with the latter thought by some to be Merlin. Cerridwen, meanwhile, is linked to Bran the Warrior through the cauldron that she gifts to him. Some even think that her cauldron—symbolizing knowledge and rebirth—was the original Holy Grail.

3Circe

Greek

Circe was the Greek goddess of metamorphosis and illusion. She was also a goddess of necromancy, skilled in using potions and drugs in her many spells. It is this connection to the magic that keeps her relevant among today’s witches.

In some traditions, Circe is regarded as the goddess who invented magic, with Homer’s Epigrams XIV calling her the daimona (spirit) of magic. Even her name is derived from the Greek word “kirko” (meaning “to secure with rings” or “hoop around”)—a reference to her association with binding magic.

While not wholly evil, Circe certainly wasn’t a “good” witch either. She was known to turn the men she came across into animals, with their minds intact to fully appreciate their predicament. When a woman named Scylla unknowingly invited Circe’s jealousy, the goddess used a potion to change her into a hideous sea monster. Finally, and perhaps most famously, Circe was the goddess who fell in love with Odysseus after he and his crew landed on her island home of Aeaea. She turned all but one of Odysseus’ crewmen into animals and forced him to live with her for an entire year. It took the help of the god Hermes to defeat her spells and free Odysseus from her grasp.[8]

2Diana

Roman

Diana is the Roman goddess of woodlands, wild animals, and hunting. In the Greek pantheon, she was known as Artemis. She was often depicted as a virgin, carrying a bow and quiver and accompanied by either a deer or hunting dogs. The spread of her cult probably influenced some myths of “The Great Hunt” found throughout pagan religions.

She was also a fertility goddess who assisted in childbirth, nursing, and healing. As the goddess of light, she represented the Moon, supplanting the goddess Luna in that role. She later became associated with Hekate and was known as a goddess of the dead.

She was originally worshiped on the Tifata Mountain and in sacred forests. Due to her affinity with the lower classes, escaped slaves could seek asylum in her temples—many of her priests were said to be former slaves. Eventually, her followers branched out from Greece and Rome and began to encompass much of the Old World. Her cult, along with that of the pagan goddesses inspired by her, was so widespread that early Christians considered her to be one of their chief obstacles.[9]

Despite Christianity’s best efforts, Diana worship is still alive and well today, with an entire branch of Wicca named after her (Dianism). She’s also one of the chief figures of various neo-pagan and Wiccan traditions. One such modern group is the Temple of Diana, a feminist group of Dianic witches with branches in Los Angeles, Wisconsin, and Michigan.

1Hekate

Greek

Hekate, above perhaps all others, is the original and official goddess of witchcraft. The “goddess of the crossroads” is also the goddess of night, magic, necromancy, the Moon, and ghosts.

According to the most common traditions, Hekate was originally a Thracian deity who—as both a Titan and the daughter of Zeus—had power over the heavens and Earth. She was originally considered a nature and lunar goddess (on par with Demeter and Artemis) and either granted or withheld blessings of abundance, victory, wisdom, and luck, depending on how her worshipers treated her.

It wasn’t until the time of the Greek tragedians that she became associated with witchcraft and death. A legend arose that she journeyed to the underworld after witnessing the abduction of Persephone by Hades—there, she became Persephone’s companion. After that, she began to be “regarded as a spectral being, who at night sent from the lower world all kinds of demons and terrible phantoms, who taught sorcery and witchcraft, who dwelt at places where two roads crossed each other, on tombs, and near the blood of murdered persons. She herself too wanders about with the souls of the dead, and the whining and howling of dogs announce her approach.”[10]

Is it any wonder that, even today, Hekate is considered the undisputed goddess of witchcraft!

Lance LeClaire is a freelance artist and writer. Look him up on Facebook and keep an eye out for his articles on Listverse.