Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

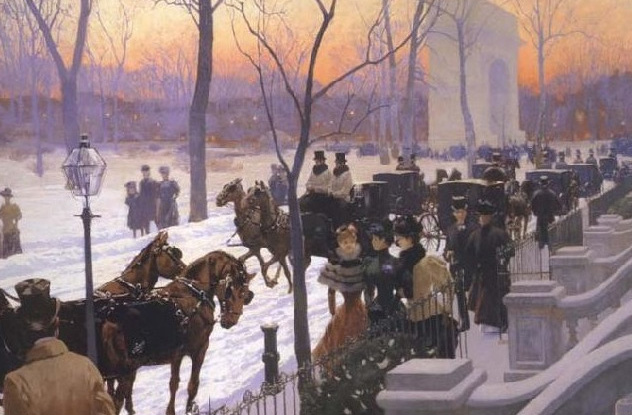

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

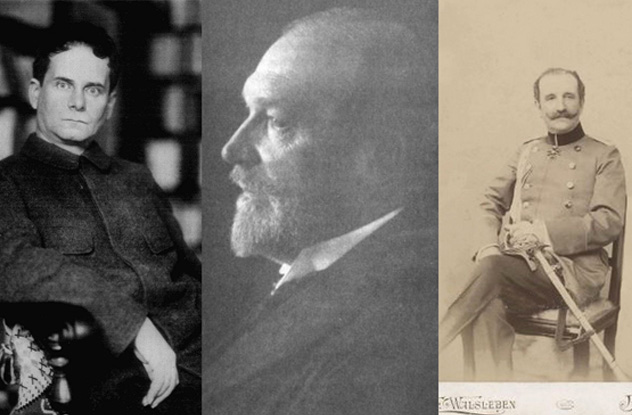

10 Mad Tales From The Life Of Germany’s Last Emperor

Some consider him Adolf Hitler’s spiritual twin. But history’s judgment of Kaiser Wilhelm II, the last German emperor, is ambivalent. Pompous and bellicose, Wilhelm was a fascinating and contradictory character. His constant saber-rattling and glorification of war kept Europeans on the edge of their seats. Obsessed with all things military, and hungering for Germany’s “place in the sun,” he’s an easy target as the sole man responsible for World War I. But the actual story, like the man himself, is more complicated.

10The Disability That Doomed The World

Wilhelm’s emotional instability can be traced to his traumatic birth on January 27, 1859. He was the first child of Prussian crown prince Friedrich III and Victoria, the eldest daughter of Queen Victoria of Britain. The doctor clumsily botched the delivery, injuring the baby’s head and neck. Wilhelm suffered nerve damage, permanently paralyzing his left arm. He was also deaf in his left ear. Throughout his childhood, Wilhelm endured futile treatments like electrotherapy and metal restraints and quack remedies such as wrapping a freshly slaughtered hare around the damaged limb.

Wilhelm’s disability may have contributed to his volatile temper. He tried to conceal his useless limb from the public. His insecurity unleashed the aggressiveness, resentment, and anger within.

He developed a desire to show himself as powerful, and he found an outlet in the army. Surrounded by the pomp and authority of the military establishment, Wilhelm fantasized about being a second Frederick the Great. Wilhelm’s ambition was such that he believed that Germany must have a finger in everybody’s pie. “Deep into the most distant jungles of other parts of the world, everyone should know the voice of the German Kaiser,” he wrote. “Nothing should occur on this Earth without having first heard him.”

All this bombast and obsession with the military was Wilhelm’s way of compensating for his disability. Wilhelm’s preference for military men excluded civilians from policymaking—a crucial factor that would ultimately lead Europe and the world into war. Who would think that a crippled left arm would have such dire consequences for humanity?

9Hatred Of Britain

Wilhelm’s strong maternal fixation bordered on erotic. His particular focus was his mother’s hands. Wilhelm wrote to her: “I have been dreaming about your dear soft, warm hands. I am awaiting with impatience the time when I can sit near you and kiss them, but pray keep your promise you gave me always to give me alone the soft inside of your hand to kiss, but of course you keep this as a secret for yourself.” In another revealing letter, he says: “I have again dreamed about you. This time I was alone with you in your library when you stretched forth your arms and pulled me down. Then you took off your gloves and laid your hand gently on my lips for me to kiss it . . . I wish you would do the same when I am in Berlin alone with you in the evening.”

Psychologist Dr. Brett Kahr theorizes that Wilhelm was testing out his growing sexual feelings on his mother. There may be something going for this idea, considering that, later in life, Wilhelm had a fetish for women’s arms. He would slowly remove a lady’s long gloves and kiss her arm from fingertip to elbow.

But Victoria, princess royal of Great Britain, did not reciprocate Wilhelm’s devotion. Having had high hopes for Wilhelm, she was very disappointed with her son’s disability and made no effort to hide her feelings from him. As a result, the boy was burdened with feelings of inadequacy. Princess Vicky was a very difficult woman who tried to mold her son into the image of a 19th-century British liberal. Wilhelm became bitter about her and her country.

His hatred deepened, in 1888, when a British doctor unsuccessfully treated his father’s throat cancer. Wilhelm burst out, “An English doctor crippled my arm, and now an English doctor is killing my father!” Wilhelm wildly imagined an Anglo-Jewish plot led by Vicky to take over Germany. He wrote that “the family shield had been besmirched and the Reich brought to the edge of destruction by an English princess who is my mother.”

Later in life, Wilhelm was paranoid about Germany’s “encirclement” by hostile neighbors, blaming his uncle, Edward VII of Britain, for orchestrating it. “He is a Satan, you cannot imagine what a Satan he is,” he said of Edward. Under Wilhelm, German diplomacy became largely an exercise in uncovering conspiracy.

Thus Wilhelm developed a kind of split personality. At times, he acted like an English gentleman, and at times, he was a disciplined Prussian. Above all, he envied the British navy. Determined to challenge British naval supremacy, Wilhelm launched a massive warship-building program that alarmed Britain and contributed to rising tensions between it and Germany.

8Lunatic On A Saddle

Relatives and members of the court feared that Wilhelm was mentally ill. Madness ran in the family, which included Ludwig II of Bavaria, who lived in his own fairy-tale dreamworld. The discharges from Wilhelm’s damaged ear nearly drove him mad. And for a ruler with one of the most powerful war machines in Europe, this entailed dire consequences.

The Kaiser’s personal rule, more than a century after the French Revolution abolished the divine right of kings, was an anachronism for an industrialized nation. Egomaniacal Wilhelm preferred to use “I” instead of “my government.” He governed on a saddle—literally. Wilhelm loved being on horseback and could remain so for five or six hours at a stretch. He sat on a saddle behind his desk at the palace because it made him feel like a warrior.

High-ranking ministers and military officers dared not disagree with him. They became fawning sycophants who assented to the Kaiser’s whim. When Wilhelm appeared before photographers hiding his left arm, his generals would follow suit and hide their own left arms. One count even allowed himself to grovel before Wilhelm in imitation of a poodle “with a marked rectal opening.” Wilhelm’s sense of humor included pulling off childish pranks, hitting, beating, and humiliating courtiers.

He had a habit of slapping men’s butts. Wilhelm formed a quasi-secret society called the White Stag Dining Club. To gain admission, men were required to tell a vulgar joke and present his posterior to the Kaiser, who would smack it with the flat of his sword.

His inappropriate behavior didn’t spare even visiting dignitaries. Once, when Italy’s diminutive king Victor Emmanuel II paid a visit to the Kaiser’s ship, Wilhelm remarked to his entourage, “Now watch how the little dwarf climbs up the gangway.”

On a visit to Jerusalem in 1898, Wilhelm and his procession of carriages found the Jaffa Gate too small and narrow to pass through. Wilhelm refused to dismount his horse and walk, as that would be beneath his dignity. He ordered a section of the wall torn down and the moat filled up so that he and his party could proceed in style. The Ottoman authorities complied, destroying the wall built by Suleiman the Magnificent in the 16th century.

Wilhelm’s personality was summed up by a courtier in 1908: “He is a child and will always remain one.”

7Uniform Fetish

Wilhelm’s obsession with uniforms was decidedly insane. He had more than 400 military uniforms—but not a single dressing gown, which he considered only suitable for wimps. Wilhelm had a squad of tailors on permanent standby in his palace. He had specific uniforms for every occasion: uniforms for attending galas, uniforms for eating out, “informal” uniforms for staying in, even uniforms to greet other uniforms. For instance, he would greet an artillery officer wearing an artillery officer’s suit, an infantryman in an infantry uniform, and so on.

At military parades, the Kaiser wore a helmet of solid gold. During the course of formal receptions, it was not uncommon for the Kaiser to change his wardrobe five or six times. Whenever he ate plum pudding, he wore the uniform of a British admiral.

Wilhelm played the fashion designer with his army’s uniforms. The gray coats, tunics, and pants were his ideas. The clothes ill suited the soldiers. They did not afford much mobility, and the tunics itched in the summer while failing to give warmth in the winter, but Wilhelm liked the style.

General Helmuth von Moltke worried that the emphasis on outward show and decoration would distract the army from the practical business of actually preparing for war. “And so,” Moltke lamented, “we deck people with multicolored ribbons as insignia, which only get in the way of handling weapons. Uniforms become more and more flashy instead of camouflaged for war. Maneuvers are now parade-like theatrical productions. Decoration is the order of the day, and behind all this grins the Gorgon head of war.”

6The Gay Knights Of The Round Table

Whether Wilhelm was homosexual or not is open to dispute. But he did openly consort with gay men. His closest friend, Prince Philipp zu Eulenberg, was outed in a scandal in 1907. Eulenberg gave Wilhelm the tenderness and stimulation he received from no one else—not even from his wife, Auguste Viktoria, who made him nervous. It was clear Eulenberg loved Wilhelm, but the Kaiser’s feelings toward Philipp were more ambiguous. The circle around Wilhelm, called the Liebenberg Round Table, was accused of forming a homoerotic ring around the Kaiser to shield him from political realities.

Beneath the domineering, arrogant, and masculine exterior, Wilhelm had a soft, delicate nature, hypersensitive and squeamish. He preferred male companionship because he couldn’t stand female conversation. He deemed the etiquette that one should consider in the presence of ladies “dreadful” and stifling. Wilhelm was happy away from Berlin society and its women and would rather spend time with his regiment at Potsdam and “those such kind nice young men in it.”

While staying with Prince Furstenberg during a hunting trip in the Black Forest, Wilhelm was entertained by the chief of the military cabinet, who danced in a pink ballet skirt. In the middle of the dance, the man fell dead from a heart attack. Wilhelm suffered a nervous breakdown that lasted several weeks as a result. He feared that the incident, with its hints of homosexuality in the upper echelons of the army, might leak out. It was successfully hushed up.

In World War I, officers were frequently promoted because the Kaiser liked their height and good looks, as if he were choosing models for magazine covers rather than picking out who would lead the army. They were mere ornamentation, just as Moltke feared.

5The Plan To Attack New York And Boston

In the late 19th century, the United States was beginning to flex its muscles on the world stage. US and German interests were already clashing in the Pacific, and Germany feared being excluded from the US-controlled Panama Canal. Wilhelm correctly saw America as a new rival and wanted it to recognize German might and superiority. To put America in its place, Wilhelm authorized Lieutenant Eberhard von Mantey to draft plans for an attack on the US.

Mantey called for an amphibious force of 100,000 men from 60 ships to land on the eastern seaboard. The naval attache at the German Embassy in Washington began scouting for suitable landing places. The first choice of targets were Norfolk, Hampton Roads, and Newport News in Virginia. Troops would take the beachhead at Cape Cod and march on Boston, while heavy cruisers would bombard Manhattan and create maximum panic. Mantey was confident of capturing the city: “Two to three battalions of infantry and one battalion of sappers should be sufficient.”

The objective of the invasion was to force President Theodore Roosevelt to negotiate a peace deal that would give Germany a free hand in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. But it showed just how much Wilhelm was out of touch with reality. Chief of staff Count Alfred von Schlieffen privately expressed fears about the feasibility of the entire scheme. Out of loyalty to the Kaiser, he went along and was even on the verge of ordering the attack on New York. But Germany had too few troops, and Schlieffen aborted the operation. The plans were finally shelved in 1907.

4The Hun Speech

Political correctness didn’t quite exist back in pre–World War I Europe, and the Kaiser gets the (dis)honor of making some outrageous statements that would make any bigot blush. Historian Barbara Tuchman called him “the possessor of the least inhibited tongue in Europe.”

The origin of the anti-Asian phrase “the Yellow Peril” is attributed to Wilhelm. He coined it in the 1880s after dreaming of the Buddha riding a dragon and threatening to invade the West. His paranoia came to the fore again when he informed his cousin, Tsar Nicholas II, that a secret Japanese army of 10,000 men was hiding in southern Mexico ready to seize the Panama Canal. Wilhelm believed a racial war would come, “Yellow vs. White.”

On July 27, 1900, Wilhelm gave a speech at Bremerhaven to German troops departing to suppress the Boxer Rebellion in China. While speaking, Wilhelm was carried away by his usual rhetoric and bombast about German military power. “Should you encounter the enemy, he will be defeated!” he said. “No quarter will be given! Prisoners will not be taken! Whoever falls into your hands is forfeited. Just as 1,000 years ago the Huns under their King Attila made a name for themselves, one that even today makes them seem mighty in history and legend, may the name German be affirmed by you in such a way in China that no Chinese will ever again dare to look cross-eyed at a German.”

The passage comparing the Germans to Attila and the barbarian Huns embarrassed the Kaiser’s diplomats. They omitted it in the official printed versions of the speech. But the damage had been done, and Wilhelm’s words turned back against him. “Hun” was thereafter used by Allied propaganda in World War I to describe the Germans and their ruthless methods.

3The Daily Telegraph Affair

Wilhelm was prone to being tactless in his dealings with other powers. Gaffes seemed to be his specialty. In October 1908, Wilhelm gave an interview to the Daily Telegraph, seeing it as an opportunity to calm tensions with the British, who were already alarmed by the German naval buildup.

It had the opposite effect. The emotionally volatile Kaiser, instead of appeasing the British, aroused their fury with statements like, “You English, are mad, mad, mad as March hares.” He accused them of being mistrustful and jealous, saying that their rebuffing his offers of friendship “taxes my patience severely.” Wilhelm implied that a majority of Germans were anti-British.

Wilhelm didn’t alienate only the British with his unfortunate choice of words. He also said that the French and Russians had egged him to side with the Boers against the British. Trying to assuage British fears, Wilhelm also hinted that the German naval buildup was directed not at Britain but at Japan. So, in a space of a single interview, the Kaiser had managed to antagonize Britain, France, Russia, and Japan.

Damage control was needed, but the Kaiser’s minions did not do their jobs. Wilhelm had obtained the transcript before it was published and gave it to his foreign minister Bernard von Bulow for review and approval. With a busy schedule, Bulow passed it to an editor at the state secretary’s office. The editor thought Wilhelm wanted it published as is, and he only proofed the form, not the contents. Bulow again didn’t care to read it and passed it on to the Daily Telegraph. Then all hell broke loose.

Bulow tried ineffectively to defend the Kaiser’s statements. But Wilhelm felt betrayed and had him replaced by Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg. Wilhelm kept a low profile in the wake of the uproar. Since Bulow knew how important the interview was, it is speculated that he deliberately allowed it to stand unaltered to exploit the subsequent fiasco to further his political ambitions. If so, his scheme backfired.

2Panicked By War

When the eve of the most terrible war humanity had known thus far arrived, Wilhelm was in a panic. Historians still dispute how much blame the Kaiser deserves for the ensuing bloodshed. While he welcomed war as a means of asserting German dominance, it appears that Wilhelm preferred a limited war, not a world one. Better still, Wilhelm would have wanted to gain prestige and power for Germany by frightening and bullying rather than fighting.

The Kaiser desperately wanted Britain to stay neutral in the event of a German attack on France and Russia. The war could have actually started during the Balkan crisis in the fall of 1912, had Germany not pulled back from the brink when Britain announced her intention to stand by France. In July 1914, Wilhelm was looking for a way out of the nightmare of a two-front war. As mobilization kicked into high gear, he had the sudden idea to leave France alone—at least for the time being—and throw the bulk of his forces against Russia.

General Moltke was brought to tears of despair at the Kaiser’s meddling with the intricate war machine. Moltke had been preparing all his life for Der Tag—“The Day”—and the showdown with France. He countered that to turn the army around from France to face east was impossible. The German mobilization plan was so perfectly drilled to the last detail that all 11,000 trains were punctually timed to pass over a specific track at 10-minute intervals. It was said that the best minds of the War College were assigned to the railway section and ultimately ended up in lunatic asylums. To reverse this clockwork machinery, Moltke argued, was to ruin it entirely.

But Moltke had exaggerated the difficulties. It could have been done, as amply demonstrated after the war. We can only speculate on how history might have been altered had Moltke obeyed Wilhelm at this crucial moment. No doubt, the impact would have been substantial.

As it was, Wilhelm simply lost control over the inexorable mobilization schedules and inflexible war plans. The Kaiser was sucked into the vortex he himself had helped create. Some historians conclude that while Wilhelm might not have deliberately instigated the war, he was doubtless an accomplice. As the war progressed, he was increasingly thrust aside by his generals and lost influence over war policy.

By autumn of 1918, it was clear that Germany would lose the war. Under pressure, Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated on November 10 and fled to the Netherlands. He never set foot in Germany again.

1Exile

Wilhelm settled in Doorn, in a 17th-century manor house he bought from Baroness Heemstra of Beaufort, later aunt to actress Audrey Hepburn. His English cousin, King George V, had condemned him as “the greatest criminal in history.” Holland’s Queen Wilhelmina, another blood relative of the Kaiser, nevertheless refused to extradite Wilhelm to face trial for war crimes. The Allies responded by threatening to blockade the Netherlands.

He had his possessions from Berlin and Potsdam brought over to Doorn in 59 railway carriages. The collection was so large that the last crates were still being opened in 1992. At Doorn, Wilhelm spent his days receiving guests sympathetic to his cause of returning to Germany and reestablishing the monarchy. Ever the conspiracy theorist, he said that Jews, Freemasons, and Jesuits were plotting to take over the world. He proposed gassing Jews to end their “nuisance.”

Wilhelm continued his tirades against Britain and France, writing in an article “The Sex of Nations” that the French were a feminine race, as opposed to the masculine Germans. In 1923, after hearing an anthropological lecture, he concluded that the British and French were racially not actually white at all, but black.

Yet despite his anti-Semitism, Wilhelm was aghast at Nazi thuggery during the Kristallnacht pogrom of November 1938, saying, “For the first time in my life, I am ashamed to be German.” A man of contradictions, indeed.

In 1940, Wilhelm was thrilled by the Nazi blitzkrieg and conquest of France, which accomplished in weeks what he hadn’t been able to do in four years. Apparently still believing that the German army was his private property, Wilhelm sent Hitler a telegram that said, “Congratulations, you have won using my troops.”

Wilhelm hoped Hitler would restore his throne. Hitler, who disliked Wilhelm, would have none of it. Embittered and disillusioned, the old Kaiser willed that his body not be returned to Germany until the monarchy was restored. He also ordered that no Nazi emblems be displayed at his funeral. The order was ignored. Wilhelm died on June 4, 1941, and at his funeral, Doorn was festooned with swastikas.

At least he got his other wish. Wilhelm’s mummified remains still rest in the mausoleum at Doorn.

Larry’s main interests are history and chess.