Creepy

Creepy  Creepy

Creepy  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

10 Real-Life Inspirations For Comic Book Characters

The best literary characters are inspired by living, breathing people. It’s the same with comic book characters. Here are 10 real people who inspired the look, the personality, or the backstory of these spandex icons.

10Clark Kent (Superman)

Harold Lloyd

The origin of Superman was a long and lengthy process. As we’ve already noted, the Man of Steel first appeared as a telepathic villain (and just as bald as Lex Luthor) in the January 1933 issue of the fanzine Science Fiction: The Advance Guard of Future Civilization. Jerry Siegel, 18, was a sci-fi fan inspired by Friedrich Nietzsche’s idealized man of the future, the Ubermensch, which is variously translated as “Overman” or “Superman.” This Ubermensch would transcend Christian values to create his own morality. Siegel wrote the story that featured this “Super-man” bent on world domination. His friend Joe Shuster illustrated the story.

Over the next five years, Siegel and Shuster dropped the hyphen and reworked Superman to be hero. Using biblical figures such as Moses and Samson and fictional heroes such as Hercules, Doc Savage, and Buck Rogers, the two young men tweaked their creation into one of the most iconic characters ever.

As avid movie buffs, Siegel and Shuster made Superman look like famous movie star Douglas Fairbanks (minus the pencil-thin mustache). His altar ego, Clark Kent (using the first names of actors Clark Gable and Kent Taylor) was modeled after another actor, Harold Lloyd. Lloyd had made a career of melding a deceptively meek look with strength and athleticism.

Recently, comic book historians have speculated that Superman’s loss of his parents and isolation from home originated from Siegel’s home life. His parents were Lithuanian immigrants, and Siegel’s father died in 1932, just six months before Superman made his first appearance.

Siegel and Shuster finally sold the rights to Superman to Detective Comics (later DC Comics) for a whopping $130. The two young men never saw another dime for their creation until the 1970s, when DC agreed to provide yearly pensions for life for the duo.

9Lois Lane

Glenda Farrell

While we are discussing Clark Kent, we should talk about the origins of his love interest, Lois Lane. There has long been an urban legend that Jerry Siegel modeled Lois after a girl he liked while he was attending Glenville High School in Cleveland.

Siegel wrote that this was untrue. He said that his girlfriend, Joanne, modeled Lane’s look for artist Joe Shuster to draw. “Our heroine was, of course, a working girl whose priority was grabbing scoops,” Siegel wrote. “What inspired me was Glenda Farrell, the movie star who portrayed Torchy Blane, a gutsy, beautiful, headline-hunting reporter, in a series of exciting motion pictures.”

Torchy Blane was a savvy news reporter who appeared in nine films from 1937–1939. Farrell played the title character in seven of them. But as time went on, Siegel said, Lane’s personality became more like Joanne, who later became his wife.

And where did the name Lois Lane come from? Actress Lola Lane played Torchy Blane in 1938. “Because the name Lola Lane appealed to me,” Siegel wrote, “I called my character Lois Lane.

8Erik Lehnsherr (Magneto)

Malcolm X

When Stan Lee and Jack Kirby debuted the first issue of X-Men in September 1963, they drew their inspiration for their opus about mutants fighting discrimination from the civil rights movement. And the inspirations for the two most powerful mutants they introduced were the two most prominent civil rights leaders of the day.

Professor X (Charles Xavier) was a gentle teacher who eschewed violence (although he wasn’t always successful) and fought prejudice by demonstrating that mutants threatened no one and could help society. He was based on Martin Luther King Jr. Magneto (Erik Lehnsherr) was blunter, advocating intimidation—even hate—and strength to combat intolerance. He was based on Malcolm X.

“[I] did not think of Magneto as a bad guy,” Stan Lee wrote. “He was just trying to strike back at the people who were so bigoted and racist. He was trying to defend mutants, and because society was not treating them fairly, he decided to teach society a lesson. He was a danger of course, but I never thought of him as a villain.”

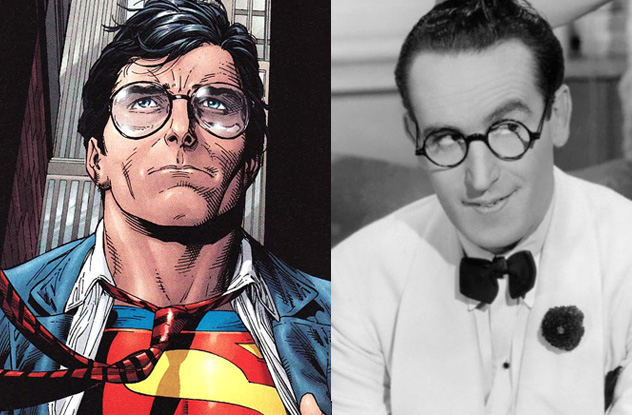

7Tony Stark (Ironman)

Howard Hughes & Elon Musk

We’ve already revealed that Stan Lee’s inspiration for Iron Man’s altar ego, Tony Stark, was Howard Hughes. The similarities between Stark and Hughes are striking: Both inherited their fortune from their father, both were industrialists and inventors, and both were playboys. Both provided military hardware to the US during the Cold War. Lee even gave a nod to the real-life millionaire when he named Tony’s father Howard.

The duality of Hughes’s life appealed to Lee. “Hughes was one of the most colorful men of the time,” he said. “He was an inventor, an adventurer, a ladies’ man, and a nutcase.” It’s not surprising that Lee describes Tony Stark in a similar manner. “[He is] rich, handsome, known as a glamorous playboy, constantly in the company of beautiful, adoring women . . . Anthony Stark is both a sophisticate and a scientist! A millionaire bachelor, as much at home in the laboratory as in high society!”

Hughes died in 1976, so when Robert Downey Jr. agreed to play Tony Stark in 2008’s Iron Man, he wanted to meet a modern version of Hughes to glean what it was like to be a billionaire, entrepreneur, and tech innovator. He turned to Elon Musk, who’d co-founded what later became PayPal and is now CEO and CTO of Space Exploration Technologies (SpaceX), the private space agency tasked with delivering supplies to the International Space Station. Downey even watched Musk’s mannerisms to make his depiction of Tony Stark believable.

Iron Man director Jon Favreau met Musk as well and was so impressed that he tweaked the Iron Man script to make Tony Stark a flamboyant Elon Musk. Favreau borrowed further aspects of Tony Stark from Larry Ellison, CEO of Oracle.

Elon Musk received a cameo in 2010’s Iron Man 2.

6Joker

Conrad Veidt

The debate over who created the Joker, arguably the best villain in comic book history, has been raging for decades. Bob Kane, Bill Finger, and Jerry Robinson all worked together at Detective Comics, and both Kane and Finger claim they had already created the Joker for the debut of Batman No. 1, when Robinson brought a playing card to them with the Joker imprinted on it. Kane claimed they used the player card as a prop, not as an inspiration.

Robinson, however, claimed he created the Joker. “I wanted somebody visually exciting,” he said. “I wanted somebody that would make an indelible impression, would be bizarre . . . I wanted a villain that had some attribute that was some contradiction in terms, which I feel all great characters have. To make my villain different, to have a sense of humor would be different . . . So once I thought of the villain with a sense of humor, I began to think of a name and the name ‘the Joker’ immediately came to mind. There was the association with the Joker in the deck of cards, and I probably yelled literally, ‘Eureka!’ because I knew I had the name and the image at the same time. I remember searching frantically that night for a deck of cards in my little room in the Bronx . . . ”

Whoever was responsible for the creation of the Clown Prince of Crime, all three credited the Joker’s look to German actor Conrad Veidt and his role as Gwynplaine in 1928’s silent classic The Man Who Laughs. The movie adapts a Victor Hugo novel where the title character, Gwynplaine, has his face mutilated into a hideous grin.

Veidt had a storied career, playing Grand Vizier Jaffar in The Thief of Bagdad, the sleep-walking Cesare in the classic The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and the Nazi major Heinrich Strasser in Casablanca. He is also credited for playing the first gay character—Paul Korner—written for the silver screen (in the 1919 movie Different From the Others).

5J. Jonah Jameson

Stan Lee

Peter Parker’s (Spider-man’s) caustic boss at The Daily Globe (and later New York City mayor) was named J. Jonah Jameson and was modeled after one of his creators, Stan Lee. “He was me!” Lee said. “He was irascible, he was bad tempered, he was dumb, he thought he was better than he was. He was the version that so many people had of me!” Steve Ditko was the other creator.

Over at DC Comics, Clark Kent’s boss, Perry White, was a big fan of Superman. Lee and Ditko liked the irony of having Peter Parker work for a boss who hated Parker’s alter ego. They liked the tension of Jameson needing photos of Spider-man to sell newspapers even as he worked to defame the superhero. Worse, Jameson hated teenagers, Marvel’s target audience. Back in March 1963, when Spider-man and Jameson first appeared, teens all over America were pushing back at perceived slights from the adults in their lives.

Jameson became the catalyst for groundbreaking moments in comics. After Lee and Jack Kirby tested the waters in 1966 by introducing the first black superhero—Black Panther—Lee gave Jameson a black editor named Robbie Robertson. Robertson became Jameson’s conscience and the second black supporting character in comic book history (the first was Gabe Jones, one of Nick Fury’s Howling Commandos). After that, African-American superheroes began to appear regularly in Marvel Comics, with Samuel Wilson (Falcon), Luke Cage (Power Man), Bill Foster (Black Goliath), Eric Brooks (Blade), Mercedes Knight (Misty Knight), and Ororo Munroe (Storm) all in the next decade. Black villains even began to appear with Noah Black (Centurius) in 1968 and Hobie Brown (Prowler) a year later.

After Ditko and Lee introduced Jameson, they had fun with adding parallels between Jameson and Lee. Jameson’s first wife was named Joan, the same name as Lee’s own wife. Jameson’s quiet secretary Betty Bryant was based on Lee’s real secretary, Flo Steinberg. And when Spider-man made it to the silver screen, Lee wanted to play Jameson. While Lee has made many a cameo in Marvel films, he never got the chance to play the character closest to his own.

4Princess Diana (Wonder Woman)

Elizabeth Marston & Olive Byrne

We’ve already discussed how Wonder Woman was created in 1941 by William Moulton Marston as a feminist ideal. A press release put it this way: “ ‘Wonder Woman’ was conceived by Dr. Marston to set up a standard among children and young people of strong, free, courageous womanhood; to combat the idea that women are inferior to men, and to inspire girls to self-confidence and achievement in athletics, occupations, and professions monopolized by men.” Pretty straightforward and laudable, right?

But Marston didn’t think women were just equal to men but superior to them. He wrote: “Frankly, Wonder Woman is psychological propaganda for the new type of woman who should, I believe, rule the world.” He added: “When women rule, there won’t be any more [war] because the girls won’t want to waste time killing men . . . I regard that as the greatest—no, even more—as the only hope for permanent peace.”

Marston was hired in 1940 by Maxwell Charles Gaines, the inventor of the comic book and co-owner of All-American Publications, the precursor to DC Comics. Gaines was already publishing Superman and Batman comics and was receiving criticism for the violence they glorified, even as World War II was heating up. Gaines wanted Marston, a well-known psychologist and inventor of the lie detector, to combat the controversy. Marston advised Gaines that his “comics’ worst offense was their blood-curdling masculinity,” recommending that they add a female superhero to All-American’s stable. Gaines gave Marston the job of developing one.

In February 1941, Marston submitted his new creation: Wonder Woman. She was a citizen of an island nation of Amazonian women who’d escaped the bondage of men in ancient Greece to form a feminine utopia where they could develop “enormous physical and mental power.”

We now know that Wonder Woman was directly inspired by the two women who lived with Marston. His wife of 25 years, Elizabeth Holloway Marston, had a bachelor, master, and law degree in an era when few women even went to college. She had helped her husband with his research into blood pressure (which led to the lie detector). So did Olive Byrne, Marston’s mistress. He had met Byrne in 1925, when Marston was Byrne’s psychology professor. When they fell in love, Marston gave his wife an ultimatum: either Byrne lived with them, or he would leave her. She agreed, and between 1928 and 1933, each woman gave Marston two kids.

While the Marstons went to work, Byrne stayed home with children, changing her last name to Richard and claiming she was a widowed sister-in-law and nanny for the Marstons. William and Elizabeth adopted Byrne’s children, and it wasn’t until 1963 that the kids found out who their mother was. Instead of a wedding ring, Byrne wore metal bracelets on her wrists, much like Wonder Woman’s own bracelets. Mrs. Marston was the one who insisted that her husband’s superhero be a woman and even supplied Wonder Woman’s famous exclamations (“Great Hera” and “Suffering Sappho”).

Both women were also feminists. Byrne was the niece of Margaret Sanger, famous birth control advocate and one of the most influential feminists of the 20th century. The Greek myth of an Amazonian utopia was a favorite of the feminist movement.

3Wolverine

Paul D’Amato

Like many comic book characters, Wolverine’s origins are complicated. He was originally created as a throwaway character tasked only to take on Hulk when he traveled to Quebec in The Incredible Hulk No. 180 (October 1974). Stan Lee and editor-in-chief Roy Thomas had told writer Len Wein and artist John Romita Jr. to create a Canadian “hero-villain” that was “named after a Northern animal.” Wein later recalled: “I was conflicted between ‘wolverine’ and ‘badger’ and finally decided badger had the connotation of mere heckling or nagging, while wolverine virtually had the word wolf in it.” Romita added: “At the time, I thought a wolverine was a female wolf!”

The next year, Wolverine appeared in Giant Sized X-Men No. 1 and officially became part of the team in X-Men No. 94. But for two years, Wolverine’s backstory and personal life were neglected. By the time artist John Byrne joined writer Chris Claremont to helm X-Men beginning in 1977, Marvel wanted to drop Wolverine as a character. Byrne, a Canadian, chafed at dumping a Canadian character and spent the next few years rounding out Wolverine, making him the icon he is today.

By the time Byrne took over, Wolverine had already been unmasked, and his signature pointy hairstyle had already been established. Byrne hardened Logan’s look, inspired by a minor character in the 1977 movie Slap Shot. Actor Paul D’Amato’s depiction of Dr. Hook was only on the screen briefly, but his crazy hair, thick sideburns, grizzled face, and wild personality seemed to fit perfectly with Byrne’s vision of Wolverine.

2Elmer Fudd

Robert Ripley

Elmer Fudd, the slow-witted foil for Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck, did not get his start as a comic book character but as regular in Warner Brothers Looney Tunes cartoons. Beginning in 1941, however, Dell began publishing Warner’s cartoon characters, including Elmer, in comics.

When Warner Brothers purchased the Vitagraph Company along with the Brooklyn Vitaphone Studios in 1925, they began to produce “talkies,” the first of which was 1927’s Jazz Singer, the first full-length movie with synchronized dialogue. Over the next three years, Warner Brothers produced hundreds of experimental short films called “Vitaphone Varieties,” featuring vaudeville acts, comedians, and singers. In 1930, Warner Brothers offered Robert Ripley, creator of “Ripley’s Believe it or Not,” a contract to produce 10-minute shorts.

Ripley was already a popular icon. His newspaper cartoon strips were syndicated around the world, and his first best seller had been published in 1929, followed by a radio program in 1930. But his Vitaphone shorts became a sensation, and Warner Brothers agreed to more, beginning a long, lucrative relationship between them.

The video and radio programs revealed Ripley’s speech impediment. His teeth protruded so significantly that he couldn’t completely shut his mouth. Despite speech lessons, his b’s came out as v’s, and he lisped his s’s. Perhaps because of his impediment, Ripley came off as shy, only making him more endearing.

It was for that reason that when Warner Brothers Looney Tunes introduced a character based on Ripley, they gave him a stuttering speech impediment. The character had a large, egg-shaped head that mimicked Ripley’s famous noggin. He was even named Egghead. In the 1939 Tex Avery cartoon Believe It or Else, several sequences appear reminiscent of Ripley’s Vitaphone shorts, with a buck-toothed, Egghead skeptical of every claim. He even wore spats and a loud suit, Ripley’s signature look. Later, Egghead would be renamed Elmer Fudd.

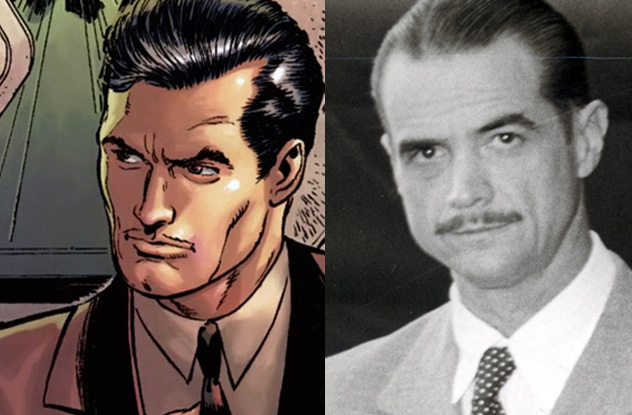

1Bruce Wayne (Batman)

Douglas Fairbanks

As they would do almost exactly a year later with the Joker, Bob Kane and Bill Finger drew their inspiration for their seminal comic book hero Batman from a movie role. Douglas Fairbanks’s depiction of Zorro in the 1920 silent classic Mark of Zorro showcased Fairbanks’s charm, humor, and (most of all) his athleticism. Kane would later say that that athletic ability, along Zorro’s mask and costume, his secret lair and his dual identity—especially the identity of a wealthy businessman—were all incorporated into Batman.

There were other contributors. Sleuths Doc Savage and Sherlock Holmes inspired Batman’s scientific proclivities. Kane wanted Batman to have wings similar to those in Leonardo da Vinci’s sketch of an ornothopter, but Finger changed it to a cape. Finger thought a hooded cowl—complete with the trademark pointed ears—looked more like a bat than Kane’s simple mask. Finger also contributed the name Bruce Wayne, which was a combination of the Scottish hero Robert the Bruce (or King Bruce I) and the American Revolutionary hero General “Mad Anthony” Wayne.

Steve is the author of 366 Days in Abraham Lincoln’s Presidency: The Private, Political, and Military Decisions of America’s Greatest President and has written for KnowledgeNuts.